Portfolio: Paintings

- Grasses 2, 1960

- Koufax Pitching,1963-65

- Stichweh Tackles,1963

- Tibor de Nagy Gallery Installation, 1964

- John Giorno, 1963

- John Giorno Dancing to Rock and Roll, 1965

- Frances Diagonal Flow, 1967

- Frances Diagonal Flow, 1967

- Enter, 1968

- Emma Lottie Marches for the Right to Vote, 1979

- The Scandalous Divorce, 1979

- Nazca, 1980

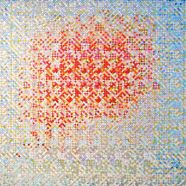

- Sunship, 1965

- Let There Be Light, 1989

- Mississippi Burning, 1965-2015

- Breaux Bridge Breakfast with Zydeco, 2014

- Lafourche Turtle, 2017

- Kendall Shaw (2014) before Escatawpa Sunrise (1968)

NOTHING ON AT ALL

In 1961, the School of Architecture at Columbia University had arranged to transport our furniture and a few possessions to New York from our home in New Orleans, and my wife, Frances, and I flew there to settle into an apartment on West 114 Street across from the campus. Ten years earlier, I had arrived by train with $25 in my pocket, having followed Surrealist painter O. Louis Guglielmi to New York City. He had returned to New York after teaching painting as an elective at Louisiana State University, where I had taken the first art course in my life with him. After that first painting class and while studying for a PhD in science, I totally redirected my energies toward art making to sail the enchanted ocean of art as far as I could.

Making art was not new for me, for I had made art of some sort all of my life. In fact, I planted (for floral color) the garden behind the family’s house in New Orleans. Important to my later paintings was the day when at eleven or twelve, I leaned my wide bed against a wall and threw paint from a #7 art brush onto a five-by-five-foot-square piece of linoleum on the floor. I saw the linoleum as a surface upon which to make a painting. Expressive splatters of paint visually recorded human energy behind the act of throwing paint.

In my art classes at LSU, Gu, as I called him, was impressed with my science background. Before arriving at LSU, I had engaged in intense scientific study in the Georgia Tech Navy V-12 officer training program from 1945–1947. This experience, combined with my time as an undergraduate student at Tulane, happily convinced me that the universe is not chaotic, but logically ordered energy in space. A good name for invented God might be Dyne. Deeply into science, I became curious about the binding of positive particles in the nuclei of atoms. I wondered why they do not repel one another. In my senior year at Tulane, a superb inventor and professor, Ruth Rogan Benerito, suggested that I accept a position she would secure for me at the government’s atomic research labs in Oak Ridge near the University of Tennessee, where I would get a PhD. I joyfully flew to the ceiling. Three weeks later, I realized, “Damn! So stupid of me. Oak Ridge is where A-bombs are produced. I will not work there to make bombs.” So, I began studies for a PhD in chemistry at LSU, where I was fortunate enough to meet art students George Dureau, Ben Freeman, and Margaret Watson, and happily scheduled the art course with Guglielmi that changed the direction of my life. At that time Gu was moving from traditional oil paint surrealism into an abstraction of flat, sharply edged shapes that echoed shapes of the steel aircraft carrier from which I flew in World War II. Clean, new, and real.

After arriving in New York City, I telephoned Gu from the 34th Street YMCA as soon as I checked in. He invited me to supper that Saturday with his family, along with Peggy and Ralston Crawford and Roselle and Stuart Davis. I had traveled by train eighteen hundred miles to study with Ralston, Stuart, and Gu where they were teaching ungraded night courses at either The New School or the Brooklyn Museum. These three fine painters, who were friends, welcomed me to the New York art scene, and I later studied with each. Gu, in fact, asked me to be his assistant. Gu brought paintings to life when he stressed the integrity of an artwork, and the integrity of the maker. Ralston advised us as his students to follow our convictions in art. Stuart told us to invent shapes and lines, keeping all shapes positive and alive. When I discovered the severe poverty of the fifty-year-old Stuart, whom I knew to be the foremost abstract artist in America, I accepted that to do art in our dollar-driven society was akin to taking a vow of poverty. But art was life—that is, necessary.

To survive, I worked as a chemical engineer in research in Chauncey, New York, for the large Stauffer Chemical Company, where I became the assistant to the sales manager in Manhattan until 1953. After learning that Mr. Stauffer would soon promote me to vice president, I resigned, certain that it would interfere with my painting. It was then that I moved to a large, unheated loft on the Lower East Side Stanton Street to paint.

My friends, with whom I had studied, painted sharp-edged shapes of flat color. At the time, Willem de Kooning was famously using large house-painting brushes to leave soft and variably expressive edges between colors. Young Gandhi Brody had painted a light cobalt blue painting with thick pine straw–like brushed needles above the surface. I saw this painting on a wall in the Rienzi Café, a Village coffee shop where I waited tables. I learned to trust and paint from fresh subconscious feelings. The brushing and soft color in the Brody painting tickled me. Brody and his friend, Wolf Kahn, hung out occasionally with other young artists who had studied with Hans Hofmann, as had some of the artist owners and the café manager. Waiting tables at the Rienzi extended my education because of all the artists, actors, poets, social activists, and existentialist customers who frequented the café, including the outrageous Maxwell Bodenheim, who wrote Naked on Roller Skates.

Reluctant in 1954 to spend another winter in my beautiful, cheap, fourteen-windowed loft without heat, I fled to tropical New Orleans, wildcatted oil wells for a while, struck a bit, and married a lovely, intelligent woman, Frances Fort. After art historian Alfred Moir introduced me to the members of the Newcomb Art school faculty at Tulane University and they had seen my paintings, I was awarded a fellowship to work toward an MFA while also working as a graduate assistant to Ida Kohmeyer, the superb abstract expressionist, who was at that time the finest painter in New Orleans. Another graduate assistant and I organized exhibitions in the school gallery. The energetic, intellectually challenging George Rickey was director of the fine art school. A visit by Mark Rothko to Newcomb to teach graduate students stimulated Ida’s painting as well as mine. Mark said that his paintings were not big, but of human scale. He told us, “After I complete a painting, I hope that someday somebody might look at it and will feel what I felt when I worked upon it.” Subconscious human communication—art matters.

My time in New Orleans was limited, as I was called back to New York to teach in the Architecture School of Columbia University, where architect Charles R. Colbert had become the highly creative new dean. He modified a large infrequently used classroom at Avery Hall, so that when not in use for a class, it was a fine painting studio for me. Chuck wanted students to experience art making from visits to my studio in order to strengthen art input into their building designs. I also began and directed an ambitious art and architecture gallery in the school.

By 1961, Guglielmi had died, but now that I was back in New York, Frances and I would visit his warm, ebullient wife, Anna Dimaggio, at whose apartment we occasionally saw Roselle Davis. With a silky puffed halo of black hair, Roselle was strikingly beautiful. Stuart was not well and remained at their apartment. Ralston and Peggy had recently visited us in New Orleans, where, alas, Ralston was soon after buried in style, accompanied by a marching jazz band. I last saw Stuart in his 67th Street apartment in his studio. Stuart’s jazz drummer friend, George Wettling, was there. Wettling had been turned on by Stuart’s 1940s jazz paintings and found jazz the same whether in paint or in music.

Also at Anna Guglielmi’s apartment, Frances and I met the extraordinary poet, John Giorno, who was pushing the Beats to early punk culture. John collaged unexpected words and sentences from everywhere, but especially from the Herald Tribune, preferring the sentences in the Tribune to the New York Times. We both used common, everyday material we had found in our art, but differently. He rejected contemporary academic poetry. I knew traditional art methods from personal research, but I had had no academic studies in art making. My love was the new abstraction.

In 1963, a newspaper photograph of visually recorded human energy caught my attention. Athletes were shown jumping in the air to recover a loose basketball. I made several paintings of silhouetted people in sports events, and, at the same time, was painting nudes of Frances and John Giorno. John Giorno brought Johnny Myers, director and part owner of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, to see my paintings of athletic events. After the painter and critic Fairfield Porter assured Myers that my abstractions were true art, Myers gave me the first of many exhibitions to be followed by more at de Nagy, and later at Lerner Heller, Anita Shapolsky, Hirschl and Adler, Skoto, and other commercial New York galleries.

In 1966, I shook up the de Nagy Gallery space by my exhibition of large, wide paintings, which visually undulated. I had photographed sections of striped dresses that my wife Frances wore. The flowing stripes over her body were captured by my camera to act in the greatly blown up stripes in the paintings.

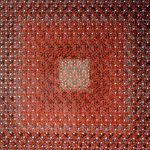

In the Cajun minimal paintings that I have been working on from 1965 to 1968 and again since 2013, I now use color panels that vary in size—human sizes related to age—following Le Corbusier’s human modular. Similar widths of wall space unite painting with wall, as if the color stripes of a Morris Louis painting were freed from their canvas. I began uniting wall spaces with painted panels in 1965, and I exhibited these paintings at de Nagy in 1968. In 1970, the Albright-Knox Gallery exhibited my Cajun minimal, multiple-color panel paintings in a Module show, which included works by the artists Navros, Huot, Ohlson, Marden, Ryman, and Mogensen. A financial squeeze along with the high cost of producing large, multiple-panel paintings stopped me from continuing this series in 1966 and for many years after.

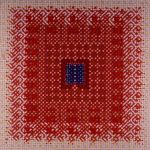

Rothko had advised his students to find and stick to a personal image in painting. I rejected that idea as a commercial strategy because it would inhibit my freedom to explore finding the real in paint. Painting was too powerful a tool to corrupt for sales. Gu had stressed integrity. Knowing all is energy in space, I knew I must follow that realization, and it continues to motivate me even today. In my rhythm over rhythm pattern paintings of the 1970s, I celebrated the rhythmic vibration of atomic particles. Life is rhythmic and patterned, a universal hum. I repeated rhythms over rhythms, and I found patterns in my patterned works that I exhibited with Pattern and Decorative artists in many venues, but I exhibited primarily at the Lerner/Heller Gallery until Richard Lerner’s death in 1982. Now, in my multiple panel Cajun Minimal paintings, there is actual energy in the form of reflected colored light combined with space: wall space.

I foolishly turned down a sale and a commission made by John Myers. One was for the Four Seasons restaurant’s huge east wall. Rothko, as I had, also felt the wall scale too unrelated to his work when he had turned that commission down. The people at #9 West 57th Street wanted to put up two twelve-panel halves of my twenty-four panel painting, one on each side of the door to their auditorium. Light was reflected on thin wall spaces between the panels, John Cage–like. Nothing becomes something real. But how could they cut my child in half? I told John Myers “no.”

In 1981, I became seriously ill with hepatitis and in 1982, my gallery dealer, Richard Lerner, died and the Lerner/Heller Gallery closed. I was too sick to paint enough for exhibitions offered by other galleries, but I kept painting and occasionally exhibiting. Life lives by consuming life. A hepatitis virus was eating my liver, but I was eating lettuce. By 2003, I was totally over the hepatitis and continued painting.

Following a beautiful exhibition of my pattern paintings, which Richard Waller curated at the University of Richmond, Tulane named me Alumnus of the Year, where at my exhibition there, I met an energetic and adventurous curator, David Houston of the new Ogden Museum of Southern Art. David later assembled a large exhibition, Let There Be Light, of paintings I had done while reading the Torah. He produced a beautiful catalogue, and Bruce Russell exhibited the collected works at Cambridge University. I sold my Soho loft in Manhattan to care for Frances full-time until her death in 2007.

Last year, John Giorno had a much-reviewed exhibition in Paris. This coming July, this show will open in Manhattan to run in several galleries here, with many of my 1964 paintings of Giorno in it. Paintings and photographs I did of twenty-six-year-old Giorno dancing naked will be exhibited in the Uptown Hunter College Gallery.

At age ninety-three, I am much too trapped by my annoying, time-devouring computer, but I paint with an assistant daily, write new wills, see too many physicians, and truly enjoy life in an old brownstone with punk poet and historian, Amos Moscrip, who makes me survive. I no longer dance but only because there is no remaining cartilage in one knee.

You paint a fascinating picture with words as well as paint! I enjoyed both the paintings and the story of your life, offering so many relationships that come off the page with the life of that energy that your art portrays making up the universe and that fed you so well.

I thank you, Joe Morris Doss. I am pleased that you enjoyed my words and the images. Thanks for letting me know, ken shaw

I can believe how much my work has in common with your work. I used to go to the Rienzi a lot, I lived in Macdougal st in the sixties. I love it. Keep going Ken.

Dearest Ken, this is a resplendent selection of dynamic, energetic paintings –exemplifying several important

periods of your varied, vibrant artistic career. All of these works are full of both exciting movement and color!

I am delighted to see here displayed, the exceptional paintings of John Giorno, as well as the later pattern paintings,often made on conjoined canvases, which are on display at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

in New Orleans, Louisiana.

My very best wishes for the upcoming exhibition at the Uptown Manhattan Hunter College Gallery!

I am delighted to be a relative of such a fascinating and multi-talented individual as Kendall Shaw!I have enjoyed his works displayed at Wake Forest, Tulane, the Ogden and his his brownstone over many years.

This is absolutely wonderful. I enjoyed this post almost as much as I did the paintings. Thank you so much, Kendall Shaw!