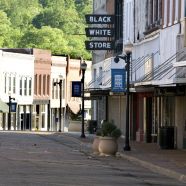

Downtown Yazoo City, 2010. Photo: © David Rae Morris (www.davidraemorris.com)

Share This

Print This

Email This

Raised to Stay

I wasn’t raised to leave. I was raised to stay.

I was taught that everything I ever needed was in Yazoo City, Mississippi, not down the road in Jackson, not up the road in Greenwood. My father was the primary proponent of this idea, though my mother believed it, too. Having finally settled in Yazoo City after going back and forth a few times to their birthplace in Lebanon, my father’s grandparents never wanted to leave Yazoo again, and they instilled that in him, when he was a boy growing up in their grocery store on West Broadway.

But back then Yazoo City wasn’t the sort of place that people left—any people, not just mine—and it wasn’t the sort of place that people much visited, either. Ruth Williams in her book Younger Than That Now tells how our provincial town got all atwitter in the 1960s, when a carload of New York boys came calling: Most of us had never seen a Yankee. My family traveled out of state once in the eighteen years I lived with them, to Memphis, and then only because the Commercial Appeal presented a plaque for our work on the high school newspaper, The Yazooan, to me and my coeditor, John Langston.

Unlike Lee Smith, I wasn’t taught not to say “me and Martha,” but I was taught not to say “ain’t,” though not by my parents, by my mother’s friend, Erma, who, one day while I was playing in her front yard, which abutted the bank of the muddy Yazoo River, told me, “Don’t say ain’t, because ain’t ain’t right.” But I adopted other local locutions, adopted them without thinking. I misplaced my inflections—said “INsurance” and “UMbrella”—and I never did anything without affixing the word fixing before the verb, as in “I’m fixin’ to go to the store.”

We never thought about these, or other, conventions. There was nothing much to make us to think about them: We had three network TV stations, a local radio station, and two newspapers, three if you counted the family-owned local. Yazoo City was an hour north of Jackson, but reachable only by rolling two-lane roads. So we lived an insular life.

***

But then, in 1970, the biggest event since the Civil War took place in Yazoo City: Our schools were integrated. Then people did come. Willie Morris, our native son, came to write about it for Harper’s Magazine and brought most of his staff with him. His cover article later became the book Yazoo: Integration in a Deep Southern Town. Other news media came, too, TV and print. Those “outsiders” mesmerized me, especially Willie; after he went back to New York, I wrote him about what was happening in Yazoo City, and to my surprise he wrote back. I wanted to get a degree in journalism, but he urged me to study liberal arts. When I was accepted on scholarship to Swarthmore College, I matriculated out of Mississippi.

I had always felt like an outsider myself in Yazoo City, being of Lebanese descent, being too tall, not having the requisite blond hair and blue eyes. And something else: With the clash over Civil Rights, I began to look on the South in a different way. I had been raised to stay, but I had to get away from the conflict roiling the town, and even my own family. But I left to find myself, not to find culture.

Though it’s true, we didn’t appreciate our own rich culture. My father thought William Faulkner was a “Commie.” In our home, we didn’t listen to the blues, had no idea that they were the basis of rock ’n’ roll. (We weren’t supposed to listen to rock ’n ’roll, either; it was hard to disobey this directive, since we didn’t have a record player.) I can recall seeing posters tacked on telephone poles, advertising B. B. King gigs in the county’s juke joints—those colorful broadsides stuck in my mind, but no white person I knew ever went to hear him. Those black ladies, Pecolia Warner and her niece, Sarah Mary Taylor, artists with their quilts, weren’t appreciated, either. Everybody had old quilts lying around.

Willie Morris showed me, and a lot of other Southerners, a path to follow in his award-winning memoir—we, too, could go “North Toward Home.” So I went to New York after I graduated from college, got a job in book publishing. I tried to forget about Yazoo City. But that place, it stayed in my mind. When I was eighteen and applying to college, I’d answered the question on the Swarthmore admissions essay “If you were to write a book, what would it be about?” by saying that I planned to write a novel about the integration of my high school. But by age forty, I still had not written that book. Then, I happened to be having dinner in the Steak House in Yazoo City with JoAnne Prichard Morris and Willie Morris, and Willie gave me the advice that changed everything. He said, “Teresa, don’t wait too long.” And so I started to write.

***

Eventually, I quit my job and moved—to Mexico. Why didn’t I move back to Yazoo City and write my book there? By now, my father had died and I was living in Yazoo about four months of every year, helping to take care of my mother. I was tempted to buy my grandmother’s beloved old bungalow and there write the books I thought I was meant to write. But instinctively I knew that I couldn’t.

I couldn’t because there was too much memory there. I needed distance to help me understand what I was writing, and why. Things look different in San Miguel de Allende’s El Charco del Ingenio than they do in Yazoo City’s Goose Egg Park. In the Goose Egg, I had many layers of memory to untangle: all the times I’d played in its perimeter bushes; picnicked under the old elm; thrown pennies in its stone fountain; driven around the park while “dragging Grand Avenue.” The slate was clean in El Charco del Ingenio botanical garden, and it was there, on long walks, amid desert cactus, that I was at last able to hear the beginning sentences of my book (no longer a novel, but a memoir).

I am not the only writer who feels this way about Mississippi, who feels its push-pull. My friend Ruth Williams has lived long stretches of her life out of state. I think of Elizabeth Spencer and Richard Ford, Steve Yarbrough and Kathryn Stockett. And I think of other Southern writers I have known, Christopher Cook from Texas and Wayne Greenhaw from Alabama, who’ve hunkered down to write in my adopted town of San Miguel. And so I write about Mississippi but live in Mexico, where there’s less memory but more perspective, where the place I was once rooted can’t be experienced, but can be imagined.

By the time I started my writing life, Mississippi had changed, economically, socially, culturally. Yazoo City had integrated, and was more at peace; but then its public schools had gradually resegregated, this time to all black, with the town itself beginning to follow suit. But integration had freed us Mississippians to finally embrace our culture in all its aspects—literature, art, music. William Ferris had founded the Center for Southern Culture at Ole Miss; Delta Blues Markers dotted the landscape; the University of Mississippi Museum and New York’s American Folk Art Museum exhibited Pecolia Warner’s quilts. Still, I couldn’t move back to Mississippi.

I think of myself now as an “in between” person—I can’t get all the way home, but I am sure about which of my two M’s is home. And I’m at least partway there.

Always enjoy knowing more of your “story” and perspectives. Another enjoyable read.

Thank you, Liz. Nice to hear from you!

Love this essay, along with Lee Smith’s, and love that you reference each other. Now I need to write “Chose to Stay.”

Thanks so much for your comment on the essay, and I await your yours!

What a wonderful piece of writing, Teresa. I really wanted this piece to go on and on. I really want to know “the rest of the story,” as a forgotten radio commentator used to say. Is this to be the intro to a new book? The old on, Buryin’ Daddy goes through my mind like it’s something on my ipod. Thank you for the very entertaining essay. Wish I could do it. I know. I know. Stop wishing . . .

Hi, Dan! So great to hear from you and thanks for your kind words. Much appreciated!

I was born in 1960 and my friend who was born in 62 were sitting here reading this article and were thrown back in those days and were discussing how things progressed I grew up and went to Manchester with Talley and Pat McGraws sons and daughters and we can relate to it because we lived it thank you so much my Grandfather was Sinclair Coleman and on my mom’s side was Wesley William Everett GREAT ARTICAL

HAPPY TRAILS