Symbols of Modernity in Early Marketing to Egyptian Women

Prior to Egypt’s formal independence from British rule in 1922, depictions of Egyptian women were rare in advertisements. Advertisements that included female figures were usually replicas of their counterparts from Western ads, for example, a woman at a Singer sewing machine, one struggling with back pain awaiting Doan’s pills, or one demonstrating motherly care with Allenbury’s food.

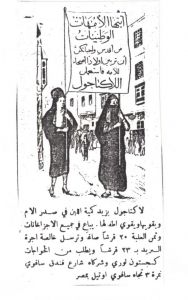

In the period between 1919 and 1922, the “1919 Revolutionary period,” women actively protested in the streets for Egyptian independence. Elite women and girls protested in gender-segregated events, whereas working-class women were more likely to protest alongside their families. The notion of Egyptians joining together in the streets was reflected in advertising, even by foreign companies, for example in the supplement for nursing mothers seen in figure 2. This ad appeared in a mainstream journal, Illustrated Quips, but it directly spoke to a female audience: “Oh nationalist mothers, the most sacred of your duties is raising healthy children for the nation, use Lactogol.”[1] The sign carried by women of distinctly different class origins symbolized unity of the county: the upper-class woman with her stylish shoes, shorter cloak, and light facial veil, while the woman of more humble origins wore slipper-style sandals, a longer dress, and an opaque niqab.

Even the act of shopping outside the home was new for elite women, who were accustomed to having goods brought to their homes by female merchants. Initially, this transition was facilitated by stores, boutiques, and small businesses that provided delivery service. Women, however, quickly discovered the joy of shopping in person. Memoirs from the turn of the twentieth century indicate that women responded to the price, comparison, and quality that could be found in the new shopping districts.[2] Fashionable outer garments were key to going out in public, and they featured prominently in advertisements in New Woman magazine in the mid-twenties (see figure 3). This image appeared under the heading “The latest fashion-Wraps.” The advertisement, which looked deceptively like an article, read, “this picture shows a woman wearing a ‘satin-crepe’ wrap in the latest style, created by Morum Department Store.”[3] It appears innocuously next to household tips, a humor section, and an advice column. The entire page is quite revealing with respect to the (relatively) new cultivation of reading for women. The humor section involved the complaint of a husband regarding his wife reading his letters, and the advice column was for mothers about what not to let their daughters read: “foreign romance novels, insane vulgarity, or [anything] with ill-mannered images. Indeed these (are all) lacking in morals. Whether your daughter is young or old or in between, preserve her with kindness and tenderness.”[4] New Woman magazine was owned by a man, Abdul Wahab Sabry, but these gems of wisdom came from a female reader—or so Sabry led the reader to believe by protecting the anonymity of the contributor.

There were truly women’s journals, for example, Women’s Renaissance was owned and edited by Labiba Ahmed. By examining the content of her advertising, it is clear that she not only participated in the new consumer modernity but also rejected hedonistic, immoral forms of consumption, particularly through the commodification of women’s bodies. First and foremost, she encouraged national consumption by promoting Bank Misr and locally owned businesses.[5]

While Ahmad did not feature numerous pictures of women or advertise many toiletries and women’s products, she did appeal to female readers in her marketing. In August 1922, she boasted that “the most influential advertisement is one published in al-Nahda al-nisa’iyya [Women’s Renaissance], because of its wide circulation among ladies.”[6] She considered her readers tasteful and modern consumers. She encouraged them to buy new-fangled gadgets, the typewriter, for example, describing a lightweight model suitable for women.[7] She advertised self-improvement through correspondence courses and radio lectures.[8] Perhaps the only indulgences she afforded her female readers were smoking locally produced cigarettes and. buying jewelry.[9]

It is worth pausing a moment and drawing some comparisons with Ladies Home Journal. Ahmed boasted about her robust circulation; however, it was nowhere near the one million American households reading Ladies Home Journal, nor did it even come close percentage-wise in relative population.[10] Both publications eschewed immodesty, but the definition was quite different in the two publications. Unlike Ladies Home Journal, there were few images of any women in Women’s Renaissance. The American publication also had prohibitions against ads exhorting installment buying, financial institutions, and tobacco. It should be noted here that it was not until 1974 that the U.S. passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and women finally had the ability to gain credit in their own name.[11] In Egypt, however, women long had access to their own credit even if they used an agent to conduct their business affairs. Thus, it was not uncommon to find advertisements for banking, real estate, or insurance in Ahmed’s Women’s Renaissance magazine or other women’s journals.[12] As for the use of tobacco, the link between tobacco and individual freedom was made clear by clever marketing agents. In 1929, Lucky Strike, the pioneer in marketing to American women, organized a “torches of freedom” march [of young women] down New York’s Fifth Avenue on Easter Sunday to drive home this connection.[13] Meanwhile, Women’s Renaissance advertisements promoted local companies. One local competitor used a flapper image to promote his “healthy” cigarettes, in addition to campaigns that touted the use of this product “for the sake of the family and children” (see figure 4).[14]

The image of a woman dressed as flapper in the Egyptian press raises the question of representation and authenticity. Some publications handled this issue by representing both tradition and modernity, side by side or hand in hand (see figures 5 and 6). The 1924 advertisement for Bon Marché features a woman in Western clothing and a woman dressed in clothing typical of the Egyptian upper classes, wearing a cloak, accessorized with a stylish headscarf and shoes. While the woman in Western dress appears “in the driver’s seat,” the Egyptian woman is interested in the raffle of the Citroen automobile at the store.[15] In a similar type of promotion from 1923, the Egyptian Shoe Factory brings together three women holding hands. All three have similar hem lengths. Note that one is wearing completely Westernized clothing; and at the other end of the spectrum, one woman wears a light facial veil in addition to her headscarf. The ad exhorts the reader to “shop with a daughter of the nation” and be “offered what is in Egyptian taste.”[16] One might argue that the Western-looking women were meant to catch the eye of the small but wealthy foreign population in Egypt; however, this group had the French and English language press (with advertisements) to feed their consumer desires.

- Figure 5.

- Figure 6.

Egyptian tastes were changing, and, under modesty cloaks, elite Egyptian women wore stylish Western clothing. Formal studio photographs were a mark of modernity and culture, the affordable, new version of the portrait. Examining images of upper-middle-class women, we see this change in clothing most strikingly (see figure 7).

As Beth Baron argued, over the course of the 1920s and 1930s personifications of the Egyptian nation increasingly depicted her in iconography as a fair-skinned, fine-featured woman. Her clothing remained modest and was decidedly Western in style. Nevertheless, she also wore symbols of the nation.[17] Advertising, too, leaned toward this new look (see figures 8, 9, and 10). These advertisements for Lux soap, Crème Cleopatra, and hair removal powder all appeared on the same page of the same journal in 1927.[18] Whether drawn by the hand of an artist at J. Walter Thompson for Lever Brothers or one of the in-house artists at al-Kashkul, the women share striking similarities in appearance.

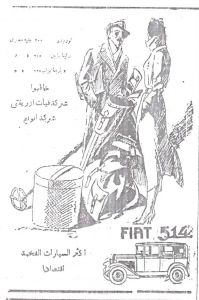

During roughly the same time period, from the late 1920s to early 1930s, advertising began to shift. By this point advertisements not only leaned toward “modern girl” conventions, but we also start to see more images of the bourgeois couple.[19] In the advertisement in figure 11, it is not entirely clear whether the woman wears a covering around her face and neck for modesty or because she is going for a ride in the Fiat. Her male counterpart, identifiable as indigenous only by his mustache and cigarette, also wears a Western-style overcoat, striking a Douglas Fairbanks pose complete with sunglasses. Between the couple sit accoutrements of modernity: golf clubs and luggage. The text of the ad explains pricing for two- and four-door models of the car.[20]

The bourgeois couples of advertising campaigns represented new social trends in companionate marriage. Historically in Egypt, one’s father or guardian made a choice that was in the economic interest of the family, and this custom applied across the social spectrum. As more men received education and entered the ranks of the middle class, many of them desired wives who would be educated companions. Where previously the bride and groom might enter into a marriage without ever seeing one another, now choice, taste, and compatibility became important.[21] These trends were criticized in some circles, as reflected in cartoons depicting this new attitude. See figure 12, in which an unmarried couple in intimate embrace are caught by the woman’s younger brother, and the (presumed) boyfriend/fiancé asks what can be done to shut him up. The woman responds that “he usually takes half a riyal (10 piastres), but I don’t know how much he takes now.”[22] In other words, it was not her first encounter!

But advertising also reflected the bourgeois couple and companionate marriage as happiness expressed through the consumption of goods. The idea of pleasing one’s mate with gifts to make her (or him) happy, and shopping together, were dominant themes of the mid-thirties through the early 1950s. In Figure 13, we see a delighted fiancée whose suitor has presented her with a new watch.[23] In Figure 14, a happy husband strolls with his wife who clutches her beautiful handbag from the “king” of purses, Hanafi Mahmud.[24] In Figure 15 an eager fiancé (or husband), wearing the Egyptian tarbouche or fez, shows his beloved that he can easily afford land and a home on his salary, purchased through monthly payments.[25] Perhaps Figure 16 sums up the optimism of the era best: it is the “story of two kisses” in which the husband and wife exchange gifts of clothing and expressions of appreciation.[26]

- Figure 13.

- Figure 14.

- Figure 15.

- Figure 16.

There were new venues for couples to share their appreciation of one another. Historically, public space had been male space. While working-class women had always had to negotiate these spaces, elite women entertained in their homes and visited their friends and families. At first, entertainment venues such as cabarets opened with days and hours for women only, but as it became more common for women to be in public spaces and as companionate marriage gained in popularity, new spaces for couples emerged.[27] Dancing and sharing an intimate evening dinner became popular pastimes.[28] In Figure 17, we see a couple dining out until three in the morning, and as the disenchanted wait staff carry them off on the table, the husband says to his wife, “Don’t you notice, they want to close the restaurant!”[29] A 1952 advertisement for Air France makes it look as though sharing an intimate (French) meal is more important than the destination (see figure 18).[30]

- Figure 17.

- Figure 18.

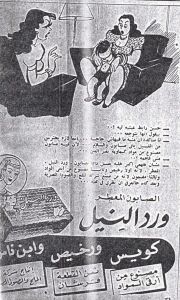

The corollary to the bourgeois couple was the bourgeois family, who also desired outings, goods, and services. Figure 19 is notable for a trend that had been underway for over a decade: attempts to create more realistic representations of Egyptian women.[31] Both women in the advertisement have long, dark curly hair, kohl-lined eyes, and full figures, and appear to be discussing the benefits of “Flower of the Nile” soap.[32] The text of the advertisement helps us better understand the expanding demographic, with claims not only of motherly concern but of “low price” and “of the people.”

There were major changes in consumer culture in the first half of the twentieth century in Egypt as evidenced by this glimpse into changing representations of women, family, and goods. At the beginning of the twentieth century, no images of Egyptian women appeared in the press, but by the middle of the twentieth century, competing versions of the “modern, Egyptian” housewife were ubiquitous in goods marketed to an expanding middle class.

[1] Mona Russell, Creating the New Egyptian Woman, Consumerism, Education, and National Identity, 1863–1922 (NY: Palgrave, 2004), 73–74.

[2] Shaarawi and Hamamsy as cited in Russell, “Marketing the Modern Egyptian Girl: Whitewashing Soap and Clothing from late-Nineteenth Century to 1936,” JMEWS 6, 3 (2010), 26–27.

[3] Advertisement for Morum Department Store, al-Mar’a al-jadida (Oct. 16, 1924), 54.

[4] From reader G.S., Ibid.

[5] Bank Misr was founded itself to promote national business and industry, in opposition to foreign-owned banks.

[6] Translation and quotation from Relli Shechter, “Press Advertising in Egypt: Business Realities, Local Meanings 1922–1956,” Arab Studies Quarterly Nos. 1/2 (2002), 51.

[7] Advertisement for Salim Haddad, al-Nahda al-nisa’iyya (Oct. 1928).

[8] Advertisements for International Correspondence School and for AUC Radio Lecture Series, al-Nahda al-Nisa’iyya, (Nov. 1928) and (June 1932), respectively.

[9] Al-Dafrawi Cigarettes was a regular advertiser and Sirgani Jewelers appeared several times in the random selection of al-Nahda al-nisa’iyya examined from 1927, 1928, 1932, 1936, and 1939.

[10] For information on Ladies Home Journal, see Jennifer Scanlon, Inarticulate Longings: The Ladies Home Journal, Gender, and the Promise of Consumer Culture (NY: Routledge, 1995).

[11] Amended in 1975 to include race, religion national origin and age, see Committee on Banking, Currency, and Housing, US House of Representatives, “Equal Credit Opportunity Act Amendments of 1975,” 94th Cong, 1st sess., May 14, 1975, Report 94–210, https://congressional.proquest.com/congressional/result/pqpresultpage.gispdfhitspanel.pdflink/$2fapp-bin$2fgis-serialset$2fa$2fd$2f0$2fb$2f13099–4_hrp210_from_1_to_22.pdf/entitlementkeys=1234%7Capp-gis%7Cserialset%7C13099–4_h.rp.210 .

[12] See for example, Ad for land for sale, ad for villa for sale, ad for Bank Misr al-Nahda al-Nisa’iyya, ran throughout 1927; (Feb. 1932); ran throughout 1936.

[13] Edward Bernays working for American Tobacco Company organized the protest as a means of reducing the stigma associated with women and smoking. Nancy Bowman, “Questionable Beauty: The Dangers and Delights of the Cigarette in American Society,” in Beauty and Business: Commerce, Gender, and Culture in Modern America, Phillip Scranton, ed. (NY: Routledge, 2001), 81.

[14] Images and discussion in Russell, Creating the New Egyptian Woman, 70–71.

[15] Advertisement for Bon Marché, al-Mar’a al-jadida (Oct. 23, 1924).

[16] Advertisement for the Egyptian Shoe Factory, al-Lata’if al-Musawwara (Mar. 12, 1923), 3.

[17] Beth Baron, Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (Berkeley: University of CA Press, 2005) 71–77, 216.

[18] All advertisements from Jan. 7, 1927, 18.

[19] On the phenomenon of “modern girl,” see Alys Eve Weinbaum, et. al., “Modern Girl as Heuristic Device: Collaboration, Connective Comparison, Multidirectional Citation,” in Modern Girl Around the World, Alys Eve Weinbaum, et. al., eds. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 1–24

[20] Advertisement for Fiat, al-Ahram, (April 5, 1930), 5.

[21] For a more complete discussion of this important topic, see Beth Baron, “The Making and Breaking of Marital Bonds in Egypt,” in Women in the Middle East: Shifting Boundaries, New Frontiers, Nikki Keddie and Beth Baron, eds. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993): 275–291 and Hanan Kholoussy, For Better or Worse: The Marriage Crisis that Made Modern Egypt (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010).

[22]Cartoon, al-Ithnayn wal-dunya (July 24, 1950), 27.

[23] Advertisement for Stores of Lisha Amin, Akhr sa’a (Nov. 8, 1936), 20.

[24] Advertisement for Hanafi Mahmud, al-Ithnayn wal-dunya (throughout 1944).

[25] Advertisement for the Abutaqiyya Company, al-Lata’if al-musawwara (Feb. 15, 1939), 6.

[26] Advertisement for the stores of Ahmad Halawa, Akhr sa’a (May 12, 1948), 12.

[27] For an example of an advertisement for women’s hours, see e.g. advertisement for Casino Bad’ia Masabni, Ruz al-yusif (July 3, 1933), 40.

[28] The story of Samia Serageldin’s Uncle Zakariah and his beautiful (though-not-forever) bride Nimette is told in Love is Like Water (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2009), 9–22.

[29]al-Ithnayn wal-dunya (Aug. 2, 1948), 28.

[30] Advertisement for Air France, Bint al-nil (June 1952), 23.

[31] See my forthcoming article, “Revealing the Hybrid Beauty: Representation of Women, the Swimsuit Controversy, and Marketing Soap in Interrevolutionary Egypt,” JMEWS.

[32] Advertisement for Ward al-nil soap, al-Ithnayn wal-dunya, (Feb. 9, 1948), 21.