W. Steven Burke and the American Folk Art Buildings Collection. Photo by Samia Serageldin

Share This

Print This

Email This

A Thousand Small Places: The American Folk Art Buildings Collection

Jane Holding queries Steven Burke on his collection of American Folk Art Buildings, based on an extensive conversation in the Hillsborough home of Steven Burke and Randy Campbell.

How do you and husband Randy Campbell find yourselves in white buildings filled with tiny buildings in Historic Hillsborough, NC?

Place is high among my favorite words. We are all captive to real and sometimes imaginary places for actual and figurative grounding. Buildings are places of course. So are mountains and vales but I’ll look most at buildings and townscapes. The design and making of a good structure ever compel. Look, love that hipped roof house!

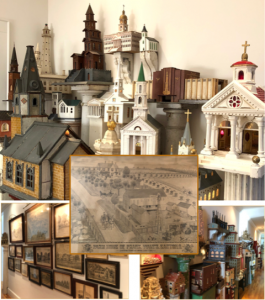

Our life here is daily and wonderfully place-based or, perhaps, place-obsessed for my part. Our American Places, seen in three ways. First, five white Greek Revival buildings. Upon our happily purchasing in 1992 a rare empty lot in this historic district, I began to design for us first a house then over time four other contiguous buildings. Greek Revival has a presentational clarity unmatched in American architectural history and seemed a right sensibility to house our growing collection and incidentally us too. Second of Our American Places: The house and two of the buildings are filled with the nation’s largest and only such collection of American Folk Art Buildings. Small three-dimensional structures inhabit purpose-designed, big three-dimensional structures. Third showing of our Places: two dimensionally, the walls are filled with nineteenth-century architectural drawings and pictures and pride of place bird’s-eye views. Look at my grand Ohio farm in 1895, commissioned in pencil from a skilled drawer of German extraction.

Here . . . it’s all in all a replete passion for American architecture and for making a place with structures large and small. Living here is revelatory and delighting, too, though dust falls insistently on 1300 small structures. Except for me, the building makers are largely anonymous . . . but we civilian architects all share passion to create places pleasing both to our vision and to others.

- Burke-Campbell home. Photo by W. Steven Burke

- Steven before one of two buildings housing the collection. Photo by Samia Serageldin

We have village connections and shared local projects like FAMILY SECRETS and IT HAD WINGS. So much of our lives have happened within the general atmosphere suggested by your buildings. Yes?

The best places give us swell people and good stories and revelations from both. You and I, Jane, and others have gained—by fate and will—enriching place junctures hereabouts. Sharings and artful expressions in this remarkable small Southern town, with learnings, clement gossip, and kinship stories over the years.

Look at you and me, unfolding in time and community, in endeavors and small structures. Friends for thirty-four years, brought together by shared friend Allan Gurganus. Among Allan’s wisest fictions is the incandescent short story It Had Wings. Upon building our Greek Revival house in Hillsborough twenty-seven years ago, Randy and I promptly named it It Had Wings to honor his friendship and that story. Allan subsequently moved up the street, a lyrical neighbor ever since. In the lovely film of the story, Jane, you startled with the strength of playing the tired old lady who sorta loves having the naked angel fall to her little backyard. You and I then found ourselves together in fellow Hillsboroughian Michael Malone’s play The Way She Died. You were better than I. Soon after, friend and opera singer Andrea Moore created the song cycle Family Secrets: Kith and Kin—a remarkable synthesis of word, commissioned music, singing, actressy narration, photos, and production, with projected photographs of Elizabeth Matheson and production direction by Fancesca Talenti . . . and also small-scale American architecture. The NC Opera Company world premiere gained you as that narrator, Jane, and Andrea as singer, and thirty-seven of our small buildings townscaping the set. We know stories live in buildings down the street. At a key juncture, you held and reflected upon one of the houses. (I do that too sometimes at home but usually to dust or reglue a piece.) Text came from Allan and other writers hereabouts: Frances Mayes, Daniel Wallace, Jeffery Beam, Michael Malone, Lee Smith, and the late Randall Kenan—friends in this richly dovetailed place. Allan observes in the work: Our village notices. Our village notices our village mostly.

Yes indeed. Ain’t that unfolding and noticing over the years great? Don’t we love such storied places and generously interactive friends. Wings overlap with artful ideas, imagination with things made and spoken, small town place making with song, you and I from 1987 until today. Also, thirty-seven American Folk Art Buildings happily got a showy performance and good notices. Isn’t that what any good building hopes?

Who made the buildings and why? What do they suggest about human nature, human beings as makers of things, as claimers of and believers in the shared, visible, created, physical world?

Wondering is irresistible and inevitable. Though the buildings seem each to hold small stories of place and persons, stories about the makers seem actually most compelling. Also, mostly unknown. Of our 1300, we know something about fewer than 100: who made and where and why and for what reason and if a real building is conveyed. Reflecting the traditional anonymity of folk art in ages less self-referential than ours, the makers were apparently more impelled by task and pleasure than by provenance. They were not fine or academic artists either.

Given culture and era—mostly from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century—the structures were likely made by males. Guys in those years were prepared to make and make do, trained in shop class, on the farm, or by the father. They were surely found in cold winter climates or isolated places, possessed of more tools and will than money to buy—and before the distractions of post–WW2 life and electronic gizmos and shopping malls. The buildings seem mostly to spring from Minnesota and Wisconsin through Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, into Pennsylvania and New England. The largest number come from Pennsylvania and its German folk culture, with Scandinavian culture an impetus in the upper Midwest. Few are from the South or beyond.

As for any artful envisoners, these guys moved from will—I’m gonna make me a church, like Granny’s in town—to imagination, problem-solving, rendering, and pleased viewing by self and others. Materials were found about the basement or barn, from wood and cigar boxes or metal bits and things shaped to new purpose, always addressing the question: how do I make small that which is usually large. Here, I’ll start with a Velveeta Cheese box and green glass from the broken hall window. The dominant colors of red, green, yellow, and off-white are both dominant in American folk art and likely found in garage or workshop.

We know some of their reasons. To accompany early model trains. To be brought out in the 20s and 30s under a scraggly Christmas tree, again reflecting German influences on both folk art and Christmas stuff. To honor and preserve, even rendered small, a loved or lost building. As a project, or for a dusty local museum. To make a family house or local building or well-known edifice resonant to the maker or to national architecture. Look, I’ve made the US Capitol or Grant’s Tomb or Zahn’s lost Racine department store. Mostly, however, they likely sprang from desire to shape, even in small scale, a place of one’s own. Cultural and behavioral explanations are working here but also compelling mystery. Why were they impelled to make? Why haven’t you? More likely, your grandfather might have.

Mark Sloan, for twenty-five years director of the Halsey Institute in Charleston, speculates about another reason: the mistress in the basement, offering some escape from wife and daily life upstairs. Likely or not, the furrowed brow maker down there does suggest that impulses might be wider than we know.

Place-making is an impulse I understand, and passion for buildings, for the actual and personal landscape. Civilian architects try it large and small.

What do the buildings express? What is particularly American about the buildings? What values are implicit in the buildings? I sense a celebration of home, of community, a native affirmation of life, a wish to elevate particular familiar places, and a proud value placed on the homemade and the self-taught. Despite the terrible political divisions in our country, the buildings remind us of enduring values we all share. They bring me longing and hope.

Many of my other favorite words shape these structures. Architecture. Passion. Imagination. Skill and craft. Also purpose and surprise and revelation.

They express delight and passion and skill and problem-solving. Present over time, they convey also artifacts judged worthy of saving. Many seem to have found their way to family storage with other lost things, like later lava lamps, until the 1920s maker’s grandchild inherited the family place and its effluvia. Even if not right for 1950s house décor, they were kept somewhere with someone for some reason unable to toss.

In total they beautifully and accurately convey American architectural history from the late seventeenth century until that split-level house in which I, and possibly you, lived in the 1960s. Does it look better small? Laid in a long chronological row, the buildings present the eras, styles, and aspirations of what we built: Colonial and Federal, Greek Revival and Victorian, Queen Anne and Italianate, Beaux Art and bold new skyscraper, Deco and Moderne and Modern. Domestic architecture is most seen, for houses are the ever important structure in lives and communities. Churches, often with complete interiors, fill a good quarter of the townscape, reflecting visual and architectural importance and maybe faith too. Factories and Ferris wheels, bridges and the castles that Americans so love somehow, gas stations and town halls and carousels, fancies and follies and banks . . . America’s built environment and townscapes over a hundred years are fully seen.

As such, the collection is both a compelling and invaluable rendering of American architectural history. Rich in shape, color, and detail. Unique, instructive, and unprecedented.

What emotions do the buildings evoke in you?

Three. Enduring pleasure, thoughts about America’s architectural carelessness, and rueful reminders that three cats are indifferent architectural preservationists.

Things can compel and have totemic calling. Looking at these structures—when I do so, for our life about them goes on and normal days pass—gives often pause and pleasure. I’m reminded that someone somewhere sometime purposefully set out to render an object, possessed of passion and pleasure and probably scant expectation of how his work might move through people and years before arriving in our hallway. I’m captured by details and skill, ever wondering about intent and maker, charmed by the mystery, and often a bit moved. I admire that earnest productive guy. I bet I’d like him too.

Evoked also: a saddening or angry reminder of this nation’s large lost architectural heritage. No nation has been as shamelessly destructive as America. Few nations have so much mistaken the new and the modernized for the valuable and the necessary. Townscapes and buildings have fallen to inattention, greed, and a pervasive belief that America expresses best with the Not Old, that building new in mean sprawl is more Manifest Destiny.

Recognition of such loss, either articulated or unconscious, seems to inform the pleasure and thinking that many viewers bring. Because made mostly between 1860 and 1950 or so, the buildings show their era and earlier architectural grounding—and convey to viewers a wistful sense of how right somehow were those houses or bungalows or fine brick factories or handsomely spired churches. Looking here, an older or even young viewer recalls the (lost) grandparent farmhouse; looking there, another wonders why that small store, like so many of these buildings, looks so much nicer than those of today. The buildings evoke atavistic feelings. Is it scale or architecture or idiosyncratic touches that compel? Do we regret the loss of earlier, appealing architecture as we compare with today’s charmless large developments and big box centers?

Some viewers report they just feel better for seeing these things; others seem to almost initiate a kind of embrace of one. Something is evoked if not always articulated. Do we always know or care why a building moves us and demands another look?

The imperative for architectural preservation has in recent decades found stronger place in America. Older or historic places are visited and protected and valued, which explains why many new developments look like our earlier porched houses and display architectural nuance or pointed Gothic-y window. Reflecting this gained or regained appreciation, persons often thank us for architectural preservation, smaller but still true to our history and earlier places. We relish this take.

With territorial ascendancy and leaping, cats display an inexplicable inattention to architecture about the house. Occasional property damage, uninsured, occurs. So can human yelling. To accept and work through these untoward events, unmoving to the cats, I started to take pictures of them where they shouldn’t be and added the Cats Kong page to our website. Everyone feels better for it.

How did this psychosis—I mean satisfying obsession—start?

My first small-scale real estate was found in 1985 at a Durham, NC, antique shop. On a shelf a $165 structure called to be mine. Having in my back pocket (this is a true story) my tax refund check for (large then, for me) $185, I promptly applied the specious financial logic gymnastics that have assisted ever since: it was sort of free. No mortgage. I liked it much and wondered if I could get more, later recognizing these to be the two hallmarks of obsession and benign addiction.

Could I find more small structures? Characteristics were set soon, seeking buildings created for whatever reasons but not as dollhouses, birdhouses, or architect models. American by making if not of architecture, for castles and deliberate Palladian sorts joined vernacular bungalows and those white New England churches. Years passed and, like Rome under Caesar, a new city arose.

This ongoing satisfying imperative found grounding in earlier years, as does happen. Some childhood was spent in Europe, through which my family passed in our big 1956 Buick and I looked through its big windows at buildings. In our five story Kensington London row house the second-floor drawing room was not much used except for my parent’s diplomatic needs, yielding a fifty by twenty feet domain on which I could lay out trains. Here and there on the overwrought Persian carpets sat bought or made small buildings.

I never stopped looking at buildings there and here, worldwide and around the house.

When did you realize you had a unique and major collection?

The collecting impulse has been endlessly addressed for its psychology and impulses and history. The impulse is mistakenly assumed to seek just numerical increase as imperative and obsession. The impulse is better understood to spring from revelatory gain. From more, we learn and can better shape understanding and analysis. One American folk art church tells something, sort of; five or fifty or . . . more . . . reveal endless richness of possibility, intent, and style. Did we expect so many ways to small render crosses and spires and stained glass? Why were maker guys in Pennsylvania more inclined to start with cigar boxes than found wood?

We collected and wondered about these things. Sellers were queried. What did they know about this Pennsylvania steel mill with blast furnace towers made from . . . car parts? In that narrative way of dealers, they reported something like got it off a fella who said it had been in his grandfather’s attic. The attic made sense, though I hated it sitting isolate all those years awaiting me, but revealed nothing about reasons for making. I soon learned that nothing had been written or studied, by curators or normal people, about the making of such buildings.

We learned: a unique juncture of architectural history, imagination, and folk art, American Folk Art Buildings (we so named them as no one else had) were a remarkably and inexplicably unexplored area and expression of American material culture. The oversight seemed regrettable and also curious, for the things—not common but also not rare and all about the house atop shelves and pedestals—clearly were shaped from personal and regional culture and were also wonderful presentations of American history.

Early talks with curatorial types were unrewarding, often showing surprising disinterest in items not in their collections or expertise. We don’t have any of those seemed insufficient an observation. A younger generation of curators and folk art respondents fortunately displays curiosity and unequivocal recognition that these buildings reveal a rich, identifiable, and defined area of national expression.

We’ve necessarily learned, surmised, asked, and posited, to bring understanding and explanation for us and others. No one else had done that, either.

Rendered Small, the so-engaging short film about us and the structures, was made by Raleigh married couple Marsha Gordon and Louis Cherry—she a NCSU film professor and he a lead modernist architect. Shown at festivals nationwide and in other settings, it elicits from viewers both questions and the surprised recognition that, even in our informationally full age, nothing like these buildings in total has ever been seen before. Also, everyone likes seeing our large bull’s-eye tabby sitting beside the yellow baroque-y church made from dress boxes from the gone Laubach’s department store in Easton, PA.

Growing attention and learning also affirmed that we have by chance first fallen upon and gathered a collection unique and nationally significant.

In our riven age of chip-based preoccupations and variant allegiances, all types and ages and persuasions find delight and often offer responses or ruminations. How rare is that? Visitors try, with mixed success, not to turn a Ferris wheel. The desire to touch is understandable.

The future of the collection?

Collections are everywhere and mostly do not survive intact. Where would they go, and why? However, responses to this collection strongly exclaim its singular importance to American architecture, history, and material culture—and that it should remain intact for viewing, learning, and pleasure.

As acceptance and presentation of hundreds of artifacts is unlikely by an existing institution, we are joined by increasing others to grant need for a new museum. I’d visit more than once the Museum of American Folk Art Buildings. Wouldn’t you? Naming opportunities will come! Friends have already offered to work in the museum shop. A site for wonderfully new artifacts will be gained—as will be substantial economic and cultural gain for the location. While New England and other states have traditionally displayed a cultural climate more attentive to such American artifacts, varied places are to be explored.

Do people have questions when they come here?

Visitors ask about all the above questions. Five others are habitual: do you have a favorite and how do you dust and where will the collection end up and is your husband as crazed as you and do you love living with the buildings.

Answers are easy: no and peripatetically and dunno so far and no, fortunately and yes indeed . . . life with American Folk Art Buildings is endlessly happy-making and revelatory.

www.americanfolkartbuildings.org

Steven’s and Randy’s lives in Hillsborough are just as magical and fascinating as their collection of American Folk Art Buildings.

Immense pleasure to be among these enchanting structures!