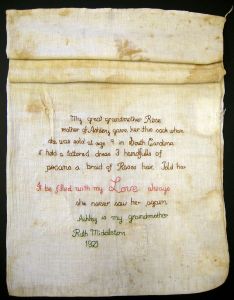

Ashley’s Sack, Courtesy Middleton Place. https://tinyurl.com/y2r5dajw

Share This

Print This

Email This

Interview

South Writ Large interviewed Tiya Miles, historian and author of All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake, winner of the 2021 National Book Award for Non-Fiction and selected as One of the Ten Best Books of the Year by The Washington Post, Slate, Vulture, and Publishers Weekly and as One of the Best Books of The Year by the New York Times, NPR, Time, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Smithsonian Magazine, Book Riot, Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, and Booklist.

Could you tell our readers about your first encounters with Ashley’s sack, and how this incredible artifact inspired you to write this book?

I first saw a photograph of Ashley’s sack on an iPad screen after following a link sent to me by the Savannah, Georgia–based journalist, Ben Goggins. The embroidered textile, which told the story of the lifelong separation of a daughter from her mother through an inhumane slave sale, was painfully profound even through the distance of a modern technological device. The sack was simultaneously beautiful and mournful, in many ways a reflection of the shared human experience. It was impossible for me to turn away from such a gripping symbol of life and love, of what it means to face hardship and nevertheless persevere. I felt compelled to set aside my other projects so that I could learn more about the object. At that time the sack was in storage, as it had been loaned out by its home institution and would soon be displayed among the inaugural exhibitions of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. I had to wait several months to see the sack in person, and during that waiting period I plunged into preliminary research. I finally got the opportunity to see the sack up close in the winter of 2016. Although by then I had been thinking about the sack for a long time, I was not prepared to absorb the emotional force of a faded fabric embroidered with words that spelled out the heartbreak not only of one parent and child, but also of an entire people.

In your book, you dive deeply into the history of Ashley’s sack, a journey that reveals much about her family history. What were some of the discoveries that surprised you most during your research?

One of the discoveries that surprised me most will probably surprise you! Before working on this book, I thought pecan trees were native to the Southeast because they are everywhere in that region now and because pecans are sold and enjoyed across the South as a regional food. The embroidery on Ashley’s sack says that Rose packed pecans for Ashley. I delved into the history of the nut and learned from food historians that in Rose’s day the pecan was transported from the Texas and Louisiana area (where pecan trees are indigenous and flourish along rivers) to South Carolina. The pecan was therefore a delicacy that graced the tables of Charleston’s wealthy residents and visitors in the antebellum era. Learning this made me see that it was even more remarkable that Rose had gotten her hands on a supply of pecans, saved them somewhere, somehow, and packed three handfuls for Ashley before the two were tragically separated.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced as you sought to reconstruct Ashley’s story as well as those of other enslaved Black women in the United States?

At the beginning of my research journey, I thought that I would be able to identify the precise location of Ashley’s birth and early childhood years, as well as the maker and original use of the cotton sack that Rose gave to Ashley. After around six months of intensive research with the aid of a Charleston born-and-raised genealogist and library specialist, Jesse Nelson, I realized that these details would not be forthcoming. The archival record was just too thin. I was coming up against the hard reality that some African American genealogists refer to as the “wall” of slavery, which severely limits our ability to trace Black individuals and family lines back to the centuries between the colonial era and federal emancipation. I knew then that I would have to approach this project in a different way, in a more creative way, and that I would have to cast a wide net to gather the necessary source materials. That epiphany inspired me to try to come closer to the sack’s history by zeroing in on the objects once packed inside (such as the pecans discussed above); it also led me to incorporate writing (memoir, fiction, poetry) by many African American women of the past and present. This rich chorus of voices lent context, depth, and insight to my interpretation of Ashley’s sack and the women who carried it.

Were there stories that you wanted to include in this book, but there may not have been space?

I wanted to write more about the theme of enslaved Black girls and the environment, but I found that this subject was taking me further away from Ashley’s particular story than was right for this book. I am currently working on a little book that is satisfying my urge to follow that conceptual track. The working title is “Trail Ready: The Little Known-History of Girls Outdoors,” and the book is forthcoming from W. W. Norton in a series of short takes on key cultural issues.

How does your book reshape the ways in which we understand the history of slavery and the experiences of enslaved women in the United States?

I hope All That She Carried offers readers many new ways to understand the history of slavery and the experiences of unfree women at that time. To choose one example, this book foregrounds the role of emotions, especially love and loss, in human history and in Black women’s lives of the past. I was struck by the reaction of a reader who pointed out how deeply she has been affected by negative stereotypes that present Black women as careless mothers who have too many children and refuse to be responsible for those children. For this reader, learning about the multitude of loving mothers in the book felt healing. Indeed, the experience of Rose and Ashley tells an oppositional and corrective story about a Black mother’s eternal love for a single child, and it helps us to see a specific case, representative of many others, in which Black family bonds persisted in the face of slavery’s assaults.

Could you share more with our readers about the role that archivists and curators have played in preserving Ashley’s sack and sharing her story with different people?

I tend to say that Ashley’s sack—its preservation and interpretation—reflects the work of many hands in the present as well as the past. A flea market shopper rediscovered the sack in the early 2000s and donated it to Middleton Place, a foundation and plantation in Charleston that shares a surname with the sack’s embroiderer, Ruth Middleton. Curators at Middleton Place analyzed and displayed the sack before loaning it to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where more curators were able to lend their insights to our collective understanding of the artifact. Scholars from various fields—anthropology, museum studies, art history, and history—have also taken part in this process that now feels like a collective endeavor of caretaking. The thousands of people who have seen the sack on exhibit in Charleston or New York City or Washington, D.C., are now part of that process too. This February 2022, Middleton Place will display Ashley’s sack in honor of Black History Month. And soon, the sack will be on view at the new Charleston International African American Museum. I encourage everyone who can to see this stunning textile in person and to become part of the living story of the sack.

What new avenues might historians follow—perhaps in examining other forms of material culture—to illuminate the untold stories of marginalized people?

Historians, humanities scholars, and creative writers can certainly look to artifacts as windows into the lives of marginalized people. In writing All That She Carried, I found numerous kinds of material things to consider, and at different scales. I looked at articles of clothing, household textiles, edibles, architectural structures, and whole cityscapes. I also thought quite a bit about quilts and beads, which did not appear in the inscription on Ashley’s sack but did turn up frequently in my archival research. If readers would like to engage more with my thinking on material culture as a means of understanding the past, they might look for my article, “Packed Sacks and Pieced Quilts: Sampling Slavery’s Vast Materials,” featured in the special issue Slavery and Its Legacies of Winterthur Portfolio: A Journal of American Material Culture (winter 2020).

What might your next project be?

I am working on several projects right now, but my next full-length book will be an intimate study of two mothers who shaped the women’s abolitionist movement in the U.S. through their writing—Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Although Stowe is more famous by far, Jacobs was every bit her literary and political contemporary. I hope to demonstrate just how enmeshed these two women’s experiences were and just how critical the analysis of enslaved women like Jacobs was to the political consciousness of free women like Stowe. The book, which has the working title “Harriet’s Mirror,” is forthcoming from Random House.