John J. Audubon’s depiction from the 1820s of two female and one male Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, courtesy of the John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove, Montgomery County Audubon Collection, and Zebra Publishing.

Share This

Print This

Email This

A Place for Ivorybills in the Present and Future South

The story of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, resident of bottomland forests in the American South and Cuba and object of many human desires, is fascinating and frustrating. The natural history of Ivorybills and the history of people interacting with this woodpecker and its forest ecosystems are the fascinating parts for me; the frustration is in knowing we have damaged the species and its habitats severely through past actions and failures to act. But even with this history, I believe we have a chance still to ensure a future for Ivorybills.

To get there, I see at least six important actions and ways of thinking. For example, we should assume, for now, that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are not extinct—they are extremely scarce but not extinct—while we continue to seek scientifically convincing evidence.

This woodpecker species probably was never abundant, and it has been listed as “endangered” by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) since 1967; however, the FWS proposed last year that it was time to rule the Ivorybill extinct, with a final decision expected in the spring of 2023. This proposal is the latest chapter in a long story of confident conclusions that the species was gone, new claims of Ivorybill encounters and moments of hope, and then another fading of prospects and awareness. Meanwhile, sharp disagreements about this bird’s fate have kept rolling on right to the present.

As mentioned above, we first need to assume that at least a small number of Ivorybills indeed exist—foraging for beetle larvae and other food, communicating with mates, roosting, nesting, possibly raising young, and most definitely avoiding humans. If reports of Ivorybills are like smoke rising from swampy southern forests, quite a few billows of smoke have appeared over many decades and into the present, and surely a few wisps have indicated living Ivorybills.

Even figuring that most reports were mistaken—someone saw a bird that in fact was a Pileated Woodpecker or some other winged creature; or maybe no bird was there at all—some sightings have been with living Ivorybills, probably among reports from Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and/or Florida, in my view. These birds have kept a small fire going for their species, and our job is to sustain and strengthen the fire.

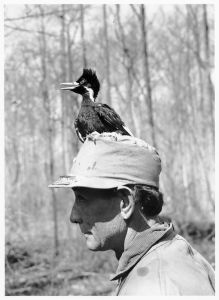

Nestling ivory-billed woodpecker and J.J. Kuhn, March 6, 1938. Courtesy of Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records (Mss. 4171), Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, LA.

Second, the FWS should keep the species listed as “endangered” and therefore entitled to federal protections and continued efforts to conserve potential habitat. The agency would have to decide that some of the information it is currently reviewing, or evidence that emerges over the next few months, likely shows living Ivorybills. Making this call would be tricky for the agency, but it already has acknowledged “substantial disagreement” about the Ivorybill’s status.

The FWS initially had until September 2022 to finalize its decision. But after receiving a raft of public comments and information related to the Ivorybill, the agency pushed back its deadline by six months. And even if the agency ends up ruling this species extinct, it likely would be less a conclusion than the latest point of contention in the debate going back at least to the 1920s, when the claim first gained traction that this woodpecker was gone.

If the Ivorybill is not gone already, then declaring it extinct surely would be its death knell, a Texas man argued in a written comment to the FWS. “We have done this bird so wrong [so] why not let it be an example of something we’ve at least tried to do right,” he urged. Many others made similar arguments to the agency. “Americans have failed over and over in our responsibilities to the natural world, and to this creature in particular,” asserted a woman in New Jersey. “At crucial points choices were made by American citizens, corporations, and agencies that were later deeply regretted.” To rule the Ivorybill extinct now would be a “final, tragic mistake,” in her view.

I started learning about this woodpecker a few years ago as a historian trying to better understand relationships between people and the rest of nature, and as a native southerner who values deeply the animals, plants, ecosystems, and landscapes of our region, even creatures large and small that are best avoided or fled with alacrity, like, say, irritable wild hogs, angry Angus bulls, red ants, southern black widows, or yellow jackets fiercely defending their nests.

Growing up in Georgia, just beyond the suburban satellites to the south of Atlanta, I tried briefly to become a serious birdwatcher, walking around my family’s farm a few times with a bird guide, binoculars, a pack of crackers, and a Coke. Lacking the necessary patience, I never got beyond recognizing the birds common around the farm, from red-winged blackbirds, blue herons, blue jays, and cardinals to the red-tailed, red-shouldered, and sharp-shinned hawks that hunted there. My go-to happy place was the farm’s lake, where I fished from a canoe, alone or with siblings or friends, and felt more at peace with myself and the world.

The tension between loss and hope can draw one into the Ivorybill story, along with this bird’s attributes: its size as the second-largest woodpecker in North America and third largest in the world, with a wingspan around 30 inches; its pearly, chisel-like bill and other distinctive features; and its elusiveness within southern bottomland forests of old hardwoods. It is tempting to see the Ivorybill as a charismatic southern character; the species inspires human imaginations more readily than other woodpeckers and many other birds.

But it is good to remember that Ivorybills never asked to be iconic or semi-famous. They never tried to impress us with their appearance and abilities. They never sought to become symbols of environmental destruction nor symbols of hope for preserving and restoring nature. We humans direct such desires at the species, often with conservationist intentions, but still grounded in our perceived needs.

What Ivorybills really needed, starting in the late nineteenth century, was for people to stop shooting them as specimens for museums and private collections and demolishing their living spaces by cutting so many of the ancient bald cypress, tupelo and sweet gums, oaks, and pines. This species evolved to rely on old-growth hardwood forests in river bottomlands and swamps, and at times the nearby pine forests, with most of this habitat located between southeastern North Carolina and East Texas.

We failed over generations to take a step back, and the scarcer this woodpecker became in the early twentieth century, the more eager were museums and collectors to acquire dead Ivorybills. And today, many of us following the story continue to want this bird to represent nature victimized by human greed, and at the same time, to persist through our depredations; we hope this species can give reassurance that we have not messed things up beyond recovery.

I admit to finding it slightly surprising that no one has come forth with a photo or video that leaves virtually no doubt for leading experts and others paying attention to this story. But it is not too surprising when you consider that the home turf for Ivorybills is not easy to access and search, and that surviving Ivorybills surely learned and taught their young to stay as far away from people as possible.

In other words, looking for Ivorybills often is no stroll along a wooded trail with binoculars and a picnic lunch. Technologies such as drones and automated cameras are important today in the study of birds and other wildlife; but the search for Ivorybills still can require paddling down bayous and streams with dense tangles of branches overhead, hoping that a water moccasin does not drop into your lap or an alligator does not get too curious and treat you as a threat; or sloshing through murky water and traversing ground with few blessed dry spots, in woods that rarely allow you to see far into the surroundings, as insects dine relentlessly at your expense.

Most of us will need to see an Ivorybill with our own eyes, through clear camera images, and perhaps in the wild for an extremely fortunate few. Rightly or wrongly, photographic images that require a hard squint and tilt of your head to see even a suggestion of an Ivorybill, sound recordings, analyses of bird calls and flight patterns, or impressive piles of bark chiseled from trees are not going to convince enough people that they exist.

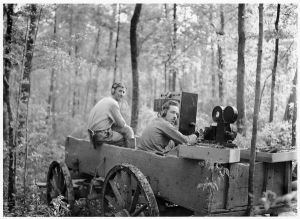

Paul Kellogg and J.J. Kuhn when sound recording of ivory-billed woodpecker was being made, April 1935. Courtesy of Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records (Mss. 4171), Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, LA.

“The only thing that’s gonna really move the needle is a very clear picture of an obvious Ivorybill,” observed biologist Geoff Hill during an online discussion last fall. “It’s one GoPro away from changing the whole story,” said Hill, who led a search in northwest Florida in 2005–6 in which his graduate students reported several sightings of Ivorybills.

Since the mid-twentieth century, people expressing belief that this species persists often have faced aspersions from others questioning their credibility and motivations. Skeptics sometimes assert that folks claiming Ivorybill knowledge and encounters do not know what they are talking about, and that, really, they need to accept that the last of the species died somewhere along the way; they should quit creating distractions from the work of protecting birds and other fauna and flora that do exist.

My third point is that we should not be too quick to dismiss or disparage people continuing to search and report their experiences, folks who are taking the FWS proposal as the next challenge rather than the end of the story. Fair enough, reports of possible sightings and recordings from searches have not been convincing to all the people who need convincing, from federal officials to leading experts to other members of the public; but the reports can be valuable if they encourage folks to keep an open mind and keep looking.

Fourth, we need a more thorough and coordinated search for Ivorybills in the most promising habitats across the Deep South, and conservation leaders from public and private organizations must summon the resources and energy for conducting that search. At the same time, we must get more comfortable with not knowing for sure yet whether this species remains; to hold this uncertainty along with the desire to know for sure. Accepting that uncertainty gives us a better chance at working together and reaching correct answers.

Tensas River near Dishroom Bend, June 1937. Courtesy of Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records (Mss. 4171), Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, LA.

The fifth point is that more of us need to acknowledge fully that human actions and inactions are responsible for the Ivorybill’s plight, and more broadly, to recognize that the world is losing something deeply meaningful, ecologically and spiritually, as we drive species to extinction. This is not about stewing in regret, but rather to take a clear, honest look at how we pushed the Ivorybill to this point and find wisdom there for creating the future.

Finally, it is crucial to remember how much remarkable natural beauty, diverse life, and wonder remain in ecosystems across the South. We have vast unrealized potential for allowing and encouraging other species and their ecosystems to thrive and for directing the human drive to build and create toward actively restoring the lands, forests, and streams that support life.

Perhaps compelling evidence will be presented soon that several or more Ivorybills are living, and enough people will see clear images so that most agree this woodpecker still exists—down but not out. Would it have any significant impact on global environmental predicaments, such as the climate crisis and extinctions around the world?

Maybe only a little. Yet we do not know really how much a widely convincing Ivorybill report or reports could energize people and boost the work of addressing the biggest environmental problems. If we gave Ivorybills more of what they need to increase their population, especially further protection of bottomland forests in the South, the story could juice our confidence for taking on those toughest challenges, like a timely word from a good friend or mentor who encourages you not to give up on a project, as great things still are possible.

Definitely let’s not give up on the ivory billed. What a fascinating story.

Intriguing! I do hope we can keep the search alive!

This is a situation I am not familiar with and I am grateful to the author for making me aware of the plight of the Ivorybill Woodpecker in such a comprehensive and well written article.

It seems to me very foolish to consider the Ivorybill gone forever when there is possible evidence to the contrary.

It is imperative that rigorous research be done over time to substantiate the claim this bird is no long with us. It also seems to me that protecting habitat associated with the Ivorybill must be done as well.

I’m a friend of Mary Jo. I’ve been a birder for over 80 years and I get your message. To have ivory-billed woodpeckers listed as extinct would certainly be The End. It would be interesting to consult a geneticist about the minimum number of I-b woodpeckers that are needed to maintain a viable species.

This is my comment. I don’t want to edit it but want it sent as is.