Chasing Summer on Nantucket

Five years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur.

—William Wordsworth, “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey”

Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

On Nantucket, everyone seems to be chasing their own white whale.

The boomerang-shaped island of Nantucket, seemingly cast into this part of the Atlantic thirty miles off Cape Cod by an ancient Greek discus thrower, might as well be named for the god of bouncing back and forth, Janus. For in visiting there we are at once looking back toward history and forward into a wished-for future. The fact that life there is lived one season at a time and seldomly year-round (except for some die-hard locals) enhances the awareness of time a visitor feels while visiting a place known for its erstwhile whaling industry, ubiquitous baskets crafted by lightship watchmen to stave off madness, abundance of oysters as fresh as they come anywhere, and an almost mandatory, preppy fashion in the (uni)form of fading red shorts. Even as visitors, we cling onto these facets of Nantucket for dear life, for if we don’t, we may lose our grip on time itself; we may crash against the rocks in a shroud of fog, joining the legions of shipwrecks ringing the small island, making widows and widowers out of our loved ones who, from their roofs, scan for us on the horizon.

Like Melville’s Captain Ahab, we pursue immortality in the most absurd ways.

Chasing summer in a place like Nantucket engenders a compressed sense of euphoria. We pack so much into two weeks or a month in the woods of North Carolina, say, or in the mountains of Tennessee or Vermont—three places I hold dear for fostering my love of different forms of education throughout my childhood and young adulthood. A three-day visit to the Grey Lady, so named for the fog that so often engulfs this island, told me that this place would be no different in the questions it would ask me about a favorite theme of mine, getting away from it all. Wordsworth’s lines add to the contrapuntal nature of (re)visiting a place with a protracted absence between visits; in this shadowy space, we are temporarily adrift.

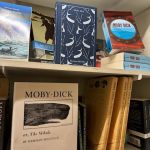

But in many ways Nantucket’s position as the historical hub of the whaling industry plants us firmly in the past. Turning a corner in a local bookstore, I encountered an entire shelf spilling over with numerous editions of Moby-Dick and assorted literature by and about Melville—who spent time in Nantucket only after writing about it—and his chef d’ouevre. Had I banged my head and woken up in the mid-nineteenth century? Since Melville never achieved much fame for his colossal novel while he was still living, I figured I had not. I greedily bought the last copy of Unpainted to the Last: Moby-Dick and Twentieth-Century American Art, a scholarly monograph grappling with the elusiveness of the whale in American art. Elizabeth Schultz, a scholar at the University of Kansas, brings Melville into the Modern. When she published this seminal work in 1995, it was almost a futuristic position to take. But looking at that shelf made me think that Melville was, here in 2024, high atop of the bestseller lists along with Elin Hilderbrand, a real-live famous Nantucket-based New York Times bestseller who has written thirty novels, many of which are set on this isle and adorn the shelves of every bookstore and the Atheneum. One of them, A Perfect Couple, became my guide to Nantucket leading up to and during my trip. The minute we landed I began to recognize places from my reading: St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, where a wedding in the novel is supposed to occur, the ritzy Monomoy neighborhood where a suspicious event takes place early on in the story, and The Nautilus restaurant.

Dinner at The Nautilus was nothing short of stunning; the crowd was giddy and buzzy. The island was in the throes of a film festival that drew some incredible talent who were in a celebratory mood. I didn’t make it to Monomoy to ogle the giant houses, but the little Episcopal church closer to the center of town impressed me, but then again, I’m always interested when I travel in seeing what form the Episcopal Church, the mothership of my faith, will take shape.

While somewhat humble in scale, the nave (designed very much in the likeness of an upside-down wooden ship as expected) boasts its horde of Tiffany windows and cools itself off not by air-conditioning but by little windows tilted open in the clerestory. Built in the early twentieth century, this church is the newcomer on the block compared to, say, the Quaker Meeting House and the Congregational Church that’s about to turn 300; but even so, it was so quaint I half expected to hear prayers canted for those who go down to the sea or for the harpooners or those who process the ambergris used to light the lamps. When I visited late one afternoon, the choir was rehearsing, and I joined in, mostly under my breath, on the harmony. The piece was a harmonious rendition of the old unison hymn, “Humbly I adore thee, verity unseen,” which I love for its focus on mystery and clouds. It sounded haunting, ominous. I guess that’s why it makes me think of incense and the Holy Spirit. And while I wasn’t in Nantucket on a Sunday, but in watching a recording of the service recently, it emerged that the gospel from Mark that week was about Jesus saving his disciples, out on the sea, from a windstorm. And the refrain of one of the hymns was “For those in peril on the sea,” widely known as the Navy Hymn, the one my grandfather, a World War II submariner, requested to be sung at his funeral. Was all this focus on the dangers of the sea just a coincidence of the lectionary? Was it making my essay easier to write? They really were singing for those in peril on the sea!

While somewhat humble in scale, the nave (designed very much in the likeness of an upside-down wooden ship as expected) boasts its horde of Tiffany windows and cools itself off not by air-conditioning but by little windows tilted open in the clerestory. Built in the early twentieth century, this church is the newcomer on the block compared to, say, the Quaker Meeting House and the Congregational Church that’s about to turn 300; but even so, it was so quaint I half expected to hear prayers canted for those who go down to the sea or for the harpooners or those who process the ambergris used to light the lamps. When I visited late one afternoon, the choir was rehearsing, and I joined in, mostly under my breath, on the harmony. The piece was a harmonious rendition of the old unison hymn, “Humbly I adore thee, verity unseen,” which I love for its focus on mystery and clouds. It sounded haunting, ominous. I guess that’s why it makes me think of incense and the Holy Spirit. And while I wasn’t in Nantucket on a Sunday, but in watching a recording of the service recently, it emerged that the gospel from Mark that week was about Jesus saving his disciples, out on the sea, from a windstorm. And the refrain of one of the hymns was “For those in peril on the sea,” widely known as the Navy Hymn, the one my grandfather, a World War II submariner, requested to be sung at his funeral. Was all this focus on the dangers of the sea just a coincidence of the lectionary? Was it making my essay easier to write? They really were singing for those in peril on the sea!

Probably and no. I keep trying to focus on the danger inherent in Nantucket life; a video at the Whaling Museum taught me how perilous life here has been and can be over the centuries. But now, watching this YouTube video of a service I wish I had attended, I’m reminded that we can be saved. The first verse of the hymn confirms this stance:

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidd’st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

And even if we die on the perilous sea, the unspoken truth implied by the hymn and made known by the disciples’ recognition of Jesus’ power is that we can still be saved.

Also found at that bookstore were multiple works by Nathaniel Philbrick, another Nantucket writer and best-selling author of nonfiction, known for his In the Heart of the Sea, which recounts the fate awaiting the Nantucket whaleship Essex, which was attacked by a whale in the Pacific in 1820, killing most of the crew. Spoiler alert: that story inspired the climactic scene in Moby-Dick. In a book I already had on my own shelves, Philbrick asks one simple but colossal question in his 2011 work, Why Read Moby-Dick? My mother gave me a copy when, in grad school, I found myself reading the tome for the third time, once in high school and twice in this graduate program alone. (Who, may I ask, had their eye on that program’s curricular scope and sequence?) The gift was part joke but mostly for encouragement, and here I am fourteen years later confronting this question again. Philbrick writes:

Contained in the pages of Moby-Dick is nothing less than the genetic code of America: all the promises, problems, conflicts, and ideals that contributed to the outbreak of a revolution in 1775 as well as a civil war in 1861 and continue to drive this country’s ever-contentious march into the future. This means that whenever a new crisis grips this country, Moby-Dick becomes newly important. It is why subsequent generations have seen Ahab as Hitler during World War II or as a profit-crazed deep-drilling oil company in 2010 or as a power-crazed Middle Eastern dictator in 2011.

Melville, therefore, is pointing us, like Janus, simultaneously backward and forward. We can read not only ourselves, but America, through his lens. I dare ask, but I fear the answer, who is our Ahab now? Who is our white whale? Can we save ourselves philosophically and morally by reading Melville in this election year of 2024?

Changing gears completely from the sacred to the mundane, I think I get even further at the essence of this place, at least sociologically. Two such details could not escape my laser focus. First are the “oversand” permits proudly displayed on the bumpers of cars and SUVs. Each year, drivers whose tires can handle the beach are issued a sticker permitting them to drive on the beach. Many parts of the island are only accessible this way. Rather than scraping the previous year’s permit off, like I would do, the driver shows off her or his trophies. These stickers tell me that (a) this person spends every season at Nantucket in this very specific beach-driving way; (b) this person is creating an illusion of permanence by displaying for all (but most importantly for himself): Hey, I’ve made it through all these years. I’m expecting to make it through another ten to twenty. All I have to do is make it through the other nine months of this year without succumbing to something terrible happening to me or my loved ones. Same goes for my car.

Second are the Nantucket Reds, which I hadn’t heard of until reading Hilderbrand on the way here. These are shorts or a jacket, shirt, hat, or belt made of brick-red cloth whose sole purpose is to fade, to show quite demonstrably the passage of time. The more faded, the more, well, Nantucket. Similar to the oversand stickers, the Reds tell the casual observer: This person has spent a lot of time on or thinking about Nantucket. They have also survived the intervening year intact, and they probably have many years left not only of these shorts but also of living!

Second are the Nantucket Reds, which I hadn’t heard of until reading Hilderbrand on the way here. These are shorts or a jacket, shirt, hat, or belt made of brick-red cloth whose sole purpose is to fade, to show quite demonstrably the passage of time. The more faded, the more, well, Nantucket. Similar to the oversand stickers, the Reds tell the casual observer: This person has spent a lot of time on or thinking about Nantucket. They have also survived the intervening year intact, and they probably have many years left not only of these shorts but also of living!

The beauty of these symbols of belonging—if not exclusivity—are illusions, memento mori, just as the oysters brought straight from the water to our table, devoured in one gulp before they have a chance to sour. The hydrangeas and roses that adorn almost every yard and trellis, too, remind us that this beauty, while succulent in June, will not last. We hasten to savor their faint colors.

For in a place built on shifting sands, at the mercy of wind, rain, even fire, everything is painfully temporal. So we create and cling to the illusion of immutability. We slap stickers on our car, we wear the faded and fading shorts, we worship the great nineteenth-century novelist, and we visit the Tiffany windows in a balancing act of honoring the past while wishing for a healthy, successful, eternal future. And all of that is more obviously in focus when you live season to season. Even at the height of summer, winter is on its way.

Because in the interim, during those gestational nine months of regular life, knowing that the summer is on a distant but attainable horizon, you have to live for it in order to attain it again in an endless series of syncopated seasons. On Nantucket, we look for Wordsworth’s soft murmur, but it’s hardly inland. It faces out into the sea.

You can memorialize your visit to Nantucket, then, with a belt or keychain embroidered with a repeating pattern of oversand permits, but I shied away from this sartorial choice. It’s too of the place. Too in-jokey. I would feel like a poseur, just as I would had I bought my own Nantucket Reds at Murray’s Toggery Shop, where the back room is filled almost cloyingly and exclusively with Nantucket Reds. Instead, I settled for some shirts and a sweater from Vineyard Vines, one of which boasts the outline of Nantucket and that people will mistake for a boomerang, and a belt ringed with lobsters. I just didn’t have the cojones to buy the more hyperlocal symbols of belonging.

But the locals we met were friendly and welcoming as were the hotel and restaurant staff, many of whom are technically outsiders themselves. One server was from Macedonia and studies in Bulgaria. She and many other island workers, many of whom are Jamaican, are here on J-1 visas for university students. They chase jobs from season to season, a fiery hunt in and of itself. I felt right at home listening to their stories.

Whether we hunt here on a real or imaginary visa, locals and visitors alike, we can all agree on one inescapable thing: the transience of this earthly existence. When we climb the proverbial rickety ladder to our rooftop, when we grasp the rail of the widow’s walk to brace ourselves against the salt-laced wind and take in our vista of the shore to see what the tide might have brought in through its great magnetic pull toward home, or what it might have cast into the chasm of the sea along with the great Leviathan, we know that eventually our oysters will turn, our overland passes will expire, our shorts will fade into oblivion, and the hydrangeas and roses will curl up against winter’s imminent blast. And while we know we could only be buoyed for a season, it is truly worth knowing that the intervening winters will come. Having that knowledge provides us with sublime tension and beauty. It is the inverse of the Romantic ideal captured in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s final lines of “Ode to the West Wind”:

O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

Each year we hold dearly onto this hoped-for beauty that each summer brings, and each year the white whale will elude us yet again.

*All photographs taken by the author.

Really enjoyed this essay. You too me to Nantucket with you, a place I have never been! Loved the imagery, history of Moby Dick, the atmosphere of the place and comparison’s to our political landscape in 2024. Well done!

Thanks, Linda! I’m just seeing your comment. I really appreciate your reading this!

Beach thoughts

Hello Mark! I know you are a writer, but it’s still impressive that three days on Nantucket generates such output – as though you spent the entire season there!

For regular beach goers, why do we take such ownership of a place we only visit once a year? I’m thinking of all the OBX and Salt Life bumper stickers I notice in traffic. And your Nantucket Reds.

Is there something about the beach and ocean, the vastness of it all, that wipes clean one’s mental slate? Is it the level of relaxation that can’t be achieved in one’s home? I like your idea of “compressed euphoria.”

Thanks for the prompt to ponder…

Hi George! I’m just seeing this comment, and it’s wonderful to think about the beach here in a bleak January. I like your questions, especially that perhaps our mental slate gets wiped clean not just by water but by the relegated, special time we set aside for a true vacation. Thanks, as always, for reading.

I loved your essay, Mark. I have read so many books set ion Nantucket, I hope I will eventually get there!