Gratitude and Treasuring Lives: Eating Animals in Contemporary Japan

In March 2009, Gifu City began to celebrate the Thanksgiving Festival for Food and Animals, later renamed Thanksgiving Festival for Food and Lives in 2013. Initially organized by the United Graduate School of Veterinary Sciences of Gifu University in conjunction with a symposium on the safety and quality of meat, the festival promoted the consumption of beef, pork, and chicken produced in Gifu Prefecture. The following year, Think Gifu, a local citizens group, took over the festival’s organization in collaboration with a local agricultural college. This time, the festival highlighted locally produced beef, chicken, and rice, products that have remained the festival’s focus ever since. That same year, the festival featured a talk by Chisen Hori, the abbot of the locally renowned Nichiren temple Myōshōji. Abbot Hori’s sermon stressed the importance of being grateful for plant- and animal-based foods and the people who labored to produce them. Since then, the festival has become an annual event that promotes local culture and agricultural products. Visitors can sample food for free, purchase local produce, and enjoy song and dance performances. In addition, the festival usually includes a workshop led by area educators or intellectuals to raise awareness that the food requires taking animal and plant lives.

Over the past ten years, an increasing number of publications and public events in Japan have drawn attention to the fact that humans must rely on animal lives for food. The moral principle at the center of this discourse is gratitude. While the connection between animals and gratitude has a long history in Buddhism, in modern Japan the meaning of repaying a debt of gratitude has shifted from an emphasis on liberating animals to consuming animals with gratitude. In other words, as meat-eating has become normative in modern Japan, even among the Buddhist clergy, a sacrificial rationale that relies on ex post facto devices has replaced anti-meat-eating discourses that have remained central features of a Buddhist identity in other parts of East Asia. The contemporary Japanese discourse of gratitude envisions an interconnected chain of becoming sustained by animal lives and culminating in human lives. As animal bodies are consumed and transformed into human bodies, humans have the moral obligation to face this reality and express their gratitude.

Debts of Gratitude and the Principle of Retribution

Historically, gratitude has been a marker of both difference and kinship between humans and other animals. In Mahayana Buddhism, animals were often described as lacking gratitude (Jpn., on; Chn., en; Skt., kṛta), also meaning “kindness.” As Hoyt Long tells us, according to Nagarjuna’s Treatise on the Perfection of Great Wisdom, gratitude is a human prerogative that leads to the cultivation of compassion, and humans who lack this virtue degenerate into beasts. In his Ōjōyōshū (The essentials of rebirth in the pure land; 985), the Japanese Buddhist cleric Genshin (942–1017) likewise associates animality with the lack of gratitude. He explains that rebirth in the beastly realm is retribution for stupidity, doing evil without regret, and lacking gratitude for receiving alms. Yet even though animals were associated with the lack of gratitude, many didactic tales also featured grateful animals.

Paradoxically, animals were expected to lack gratitude but became paragons of this same virtue to teach humans a lesson. The Buddhist cleric Nichiren (1222–82), for example, uses this reasoning in The Opening of the Eyes (1272) when he argues that those who fail to repay their debt of gratitude to the Lotus Sutra are, in fact, beasts who know no gratitude. He juxtaposes this moral deficiency with the examples of Maobao’s white turtle and the great fish of Kunming Pond, both of which excelled at repaying their debt of gratitude to the humans who saved them. He ends by asking why, if even animals know how to repay a debt of gratitude, a person claiming to be worthy could fail to do so. Even though gratitude was presumably a human virtue and those who lacked it were regarded as inhumane and beastly, exceptional animals served to illustrate the moral imperative to show gratitude. Nichiren was alluding to a long tradition of gratitude tales that can be traced back to India and China. For instance, in the Golden Light Sutra, the Buddha, in his previous life as Jalavāhana, is generously rewarded by the fish he saved during a drought. After the fish are reborn in Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, they shower him with jewels and flowers. This scripture became one of the texts on which East Asian ritual animal releases were modeled.

In China, gratitude tales involving animals became a popular genre. In such didactic tales, animals were depicted as doling out generous rewards to humans who showed them kindness and as repaying debts of gratitude in kind—saving a human life for being saved from certain death or freeing from imprisonment humans who had released them. Conversely, animals wronged by humans would mete out equivalent punishment for the cruelty they had experienced. Such tales taught powerful lessons about karmic retribution and reward. They also carried strong messages against killing or harming animals and endorsed the release of living beings.

Similar lessons also appear in ancient and medieval Japanese didactic tales. For instance, the Nihon ryoiki (Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition; late eighth or early ninth century) and the Konjaku monogatari (Tales of Times Now Past; ca. 1100) portray animals that save the lives of their human benefactors to recompense a debt of gratitude, while humans who harm animals find their lives imperiled. Such tales encouraged humans to emulate animal paragons of virtue and cautioned against killing animals. As the Nihon ryōiki explains, “Even an animal does not forget gratitude and repays an act of kindness. How, then, could a righteous man fail to have a sense of gratitude?” and “Even an insect which has no means of attaining enlightenment returns a favor. How can a man ever forget the kindness he has received?”

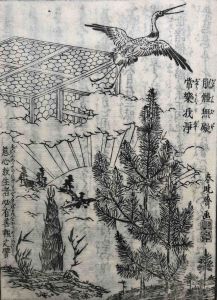

Significantly, as in medieval China, ancient and medieval Japanese gratitude tales about animals tend to link karmic retribution and repaying a debt of gratitude to not killing animals and releasing life. The following story from the Nihon ryōiki, which also appears in the Konjaku monogatari, is a good example of this connection. After his death, a man from Settsu Province who had previously sacrificed seven oxen to a Chinese divinity is brought before King Enma, the judge of the underworld. The seven oxen seek their revenge, but because the man had eventually given up such sacrifices in favor of releasing life, he is rescued by the countless small animals he liberated and is safely returned to life. In other words, killing or sacrificing animals was closely associated with illness and premature death, whereas sparing animal lives was thought to prolong life and lead to karmic rewards (Figure 1). This discourse of refraining from killing and releasing life became especially widespread in the early modern period under the influence of similar discourses in Ming-Qing China.

Illustration of the Karmic Rewards of Life Releases from the 1812 edition of Junshō’s Hōjō yorokobi gusa (Jottings on the Joys of Releasing Life). The image shows symbols of good fortune and prosperity: a crane, bamboo shoots, and pine saplings. Hinting at the subject of life releases, the crane appears to be emerging from an open cage in the upper left-hand corner. The background shows a setting sun, alluding to the promise of salvation in the Buddha Amida’s Western Pure Land (image in the author’s collection).

Gratitude and Animal Memorial Rites

At the same time, as animals became increasingly commodified in early modern Japan, new ritual technologies allowed people involved in killing animals for their livelihood to express gratitude for the animals whose deaths sustained them. Rather than supporting the abstention from animal flesh or avoiding killing animals, memorial rituals for animals canceled out the karmic burden incurred by such acts. Whaling communities, for instance, were among the first to conduct memorial rites for the animals they killed, acknowledging the animals’ death as a blessing for their communities while also averting potential retribution from the dead whales. While the whalers showed empathy for the plight of the whales, killing the animals was also regarded as inevitable, even fated, and as long as the whalers did not waste any part of the whales’ bodies, the whalers could atone for the violence against the whales by holding annual memorial rites for them.

Wooden grave tablets (tōba) memorializing pets and lab animals in a pet cemetery at a Buddhist temple in the Tokyo area. Several sponsors are pet stores, pharmaceutical companies, and research institutions (photo by the author).

Such animal memorial rituals have continued to the present (Figure 2). As Hirochika Nakamaki argues, public memorial rituals, including those for animals, serve as ex post facto devices that help the living deal with premature death, but in the modern period, such memorials tend to rely on the concept of gratitude rather than emphasizing the propitiation of potentially vengeful spirits. For Nakamaki, modern animal memorial rituals have played an important role in justifying the production and consumption of animal-based goods. In other words, the expression of ex post facto gratitude does not curb consumption but actually endorses it. Ikuo Nakamura has also critiqued the rationale behind such memorial rites. He argues that they support rampant consumption by providing participants with an opportunity to assuage their guilt without ever having to change their exploitative practices.

Arguably, in postwar Japan, the notion of vengeful retribution did not disappear entirely, but often it was not voiced explicitly. Instead, the concept of gratitude was embedded in a sacrificial rationale that cast animals as willing victims to their own destruction for the benefit of Japanese society and consequently forestalled negative repercussions from the act of killing. A survey of memorial services for laboratory animals published in the Japanese Journal of Human-Animal Relations illustrates the confluence of spirit propitiation (36 percent) and the expression of gratitude (43 percent) as the primary motivations for such rituals. It should also be noted that since rituals for laboratory animals are often conducted at public research institutions, they are sometimes termed a “thanksgiving festival” (kanshasai) rather than a “memorial rite” (kuyō) or “spirit-propitiation rite” (ireisai), both of which carry religious connotations. Thus, the commemorative rite is secularized to avoid violating the separation of religion and the state. In addition, the name highlights that the rite is a formal expression of gratitude.

Treasuring Life and Endorsing Grateful Consumption

Significantly, expressing one’s respect for life (15 percent) was the third-most-cited reason for memorial rites for laboratory animals in the survey mentioned above. This theme points to an emerging discourse linking the ex post facto expression of gratitude with valuing life—a rationale that also informs Gifu’s Thanksgiving Festival for Food and Lives. The combination of gratitude, valuing life, and meat consumption has likewise become a popular theme in several recent children’s books that are aimed to instill in the young a sense that they are valuing life by eating meat and not wasting food as long as they utter a heartfelt “Itadakimasu” and “Gochisōsama” before and after the meal.

One example of this discourse in contemporary children’s literature is the picture book Shinde kureta (They died for me; 2014) by award-winning poet Shuntarō Tanikawa (b. 1931). Nowadays, most people in Japan only purchase meat at supermarkets or restaurants without ever encountering the living animals whose flesh they are about to consume. Tanikawa, however, brings children face-to-face with the reality that meat is the flesh of animals. The text of the book, spoken in the voice of a young boy, is short enough to be cited here in full (translation mine):

The cow

Died for me

And became a hamburger

Thank you cow

Actually

The pig also died for me

As did the chicken and

Sardines and mackerel pike and

salmon and clams

A lot of beings died for me

I cannot die for anybody

Because nobody eats me

Besides if I died

Mother would cry

Father would cry

As would Grandma and my little

sister

That’s why I live

The cow’s share and the pig’s share

And the shares of the living beings

that died for me

All of them (Tanikawa 2014)

Shinde kureta strongly endorses meat consumption as a means of human survival. As author Tanikawa states on the dust jacket, “If living beings didn’t eat living beings, they would not go on living. Humans are actually living thanks to other living beings.” The narrative justifies meat consumption by depicting how animal flesh is transformed into healthy, strong human bodies.

The narrative of Shinde kureta conceals human agency in the animals’ death but does not shrink away from death itself. The animals are portrayed as willingly sacrificing their lives to sustain humans, who are described as inedible in contrast to other animals. Yet the book’s illustrations visually allude to the bloody reality behind the production of meat. The words “died for me” appear in white characters on a black background, suggesting death. On the opposite page, bold brushstrokes of red and white evoke splashing blood. A later double page spread shows the shady, yellowish outlines of various food animals against a brown background—hinting at the dark, lingering presence of animal spirits. Despite alluding to the deathly aspects of meat consumption, the book ends on a life-affirming note as the protagonist promises to live the animals’ lives in their stead. By choosing to live life to the fullest, humans can lead interrupted animals’ lives vicariously. The final illustration shows the young boy framed by a rising sun—a symbol of life, hope, and light, and a strong counterpoint to the images of death, darkness, and gloomy shadows. Shinde kureta suggests an interlinked chain of becoming that culminates in vigorous human lives.

These sentiments have also taken root in contemporary Japanese Buddhism. The clearest example is the new meal verses adopted by the Nishi Hongwanji branch of Jōdo Shinshū and published by the Doctrinal Mission Center (Kyōgaku Dendō Sentā) in 2009. The sectarian leadership decided to shift the focus from Amida Buddha to the sacrifice of lives. The sectarian leadership replaced an earlier version of the verse recited before the meal, “Thanks to the Buddha and to everybody, we were blessed with this feast;’ with the new wording “Thanks to many lives and everybody, we were blessed with this feast.” According to the official commentary, the substitution of “many lives” for “the Buddha’’ was intended to dispel the misunderstanding that the Buddha was like a creator divinity who had created animals so that they could serve as food for humans. Instead, the new phrasing was meant to highlight “that the sacrifice of ‘many lives’ and our indebtedness to the Buddha are different things” and to express remorse.

Jodo Shinshu may be singular in having officially incorporated the idea of gratitude for the sacrifice of plants and animals into its sectarian teachings, but clerics of other Buddhist schools embrace similar positions, as indicated by Nichiren cleric Chisen Hori’s participation in Gifu’s 2010 Thanksgiving Festival for Food and Animals. Similarly, the annual Gion Hōjōe in Kyoto, an event organized by the Tendai temple Sekizanzen’in, is performed to express gratitude toward the plants and animals consumed as food (Figure 3). The event typically features a Dharma talk by Kanshō Kayaki (b. 1946) (currently the vice-abbot of Zenkoji’s Daikanjin), in which Kayaki bemoans the waste of food in modern Japanese society and exhorts his audiences to be grateful for the animals and plants they consume.

Releasing sweetfish during the Gion Hōjōe in Kyoto

Conclusion

Meat-eating has long been considered problematic in Buddhism: many East Asian forms of Buddhism categorically reject meat-eating as a whole, whereas the orthodox vinaya, such as the Ten Recitations Vinaya, only allows the consumption of so-called clean meat and prohibits as unclean any meat that has been killed explicitly for the monastic community. In contrast, as Richard Jaffe has demonstrated, the consumption of any kind of meat has become commonly accepted in modern Japanese Buddhism. Once considered an antinomian practice peculiar to Jōdo Shinshu, meat-eating became a potent symbol of a strong modern nation and modern Buddhism from the Meiji period (1868–1912) onward, as Richard Jaffe has shown.

Contemporary Japanese arguments for the consumption of meat, including those made by Buddhist clerics, have adopted a sacrificial reasoning. Unlike earlier Buddhist discourses that stigmatized meat consumption or averted the human gaze from the slaughter, contemporary Japanese discourses propose that witnessing the killing of animals makes consuming meat wholesome as long as humans avoid wastefulness and express their gratitude for the animals’ sacrifice. Recognizing the indebtedness of humans to animals creates an opening for reflection that makes it possible to see animals as subjects and destigmatize the labor involved in animal slaughter and the manufacture of animal-based products. Yet while the expression of gratitude validates the deaths of animals, it does not necessarily better their lives. On the contrary, the expression of remorse and gratitude can serve to spur consumption without the need for altering any exploitive practices inherent to the modern animal-industrial complex.

This essay originally appeared in Dharma World, January–June 2017, pp. 15–19.

Further Reading

Ambros, Barbara. 2012. Bones of Contention: Animals and Religion in Contemporary Japan. University of Hawai’i Press.

Ambros, Barbara. 2014. “The Third Path of Existence: Animals in Japanese Buddhism.” Religion Compass 8, no. 8: 251–63.

Ambros, Barbara. 2019a. “Cultivating Compassion and Accruing Merit: Animal Releases during the Edo Period.” In The Life of Animals in Japanese Art, edited by Robert T. Singer and Kawai Masatomo, 16–27. Princeton University Press.

Ambros, Barbara. 2019b. “Partaking of Life: Buddhism, Meat-Eating, and Sacrificial Discourses of Gratitude in Contemporary Japan.” Religions 10, 279 (April), https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040279.

Ambros, Barbara. 2021. “Tracing the Influence of Ming-Qing Buddhism in Early Modern Japan: Yunqi Zhuhong’s Tract on Refraining from Killing and on Releasing Life and Ritual Animal Releases.” Religions (Special Issue: Chinese Influences on Japanese Religious Traditions) 12, 889 (October), https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100889.

Jaffe, Richard M. 2005. “The Debate over Meat Eating in Japanese Buddhism.” In Going Forth: Visions of Buddhist Vinaya, edited by William M. Bodiford, 255–75. University of Hawaii Press.

Kyōgaku Dendō Sentā, ed. 2009. Shin ‘Shokuji no kotoba’ kaisetsu. Dōbōkai.

Long, Hoyt. 2005. “Grateful Animal or Spiritual Being? Buddhist Gratitude Tales and Changing Conceptions of Deer in Early Japan.” In JAPANimals: History and Culture in Japan’s Animal Life, edited by Gregory Pflugfelder and Brett Walker, 21–58. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan.

Nakamaki, Hirochika. 2005. “Memorials of Interrupted Lives in Modern Japan: From Ex Post Facto Treatment to Intensification Devices.” In Perspectives on Social Memory in Japan, edited by Tsu Yun Hui, Jan van Bremen, and Eyal Ben-Ari, 44–57. Global Oriental.

Nakamura, Ikuo. 2001. Saishi to kugi: Nihonjin no shizenkan, dōbutsukan. Hōzōkan.

Nakamura, Kyoko M., trans. 1973. Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The “Nihon ryōiki” of the Monk Kyōkai. Harvard University Press.

Ōue, Yasuhiro, et al. 2008. “Nihon ni okeru seimei kagaku gijutsusha no dōbutsu jikken ni kansuru ishiki: Seimei kagaku jikken oyobi dōbutsu ireisai ni kansuru ankēto chōsa no bunseki.” Hito to dōbutsu no kankei gakkaishi (Japanese journal of human-animal relations) 20: 66–73.

Pu, Chenzong. 2014. Ethical Treatment of Animals in Early Chinese Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices. Cambridge Scholars Press.

Tanikawa, Shuntarō. 2014. Shinde kureta. Kosei Publishing.