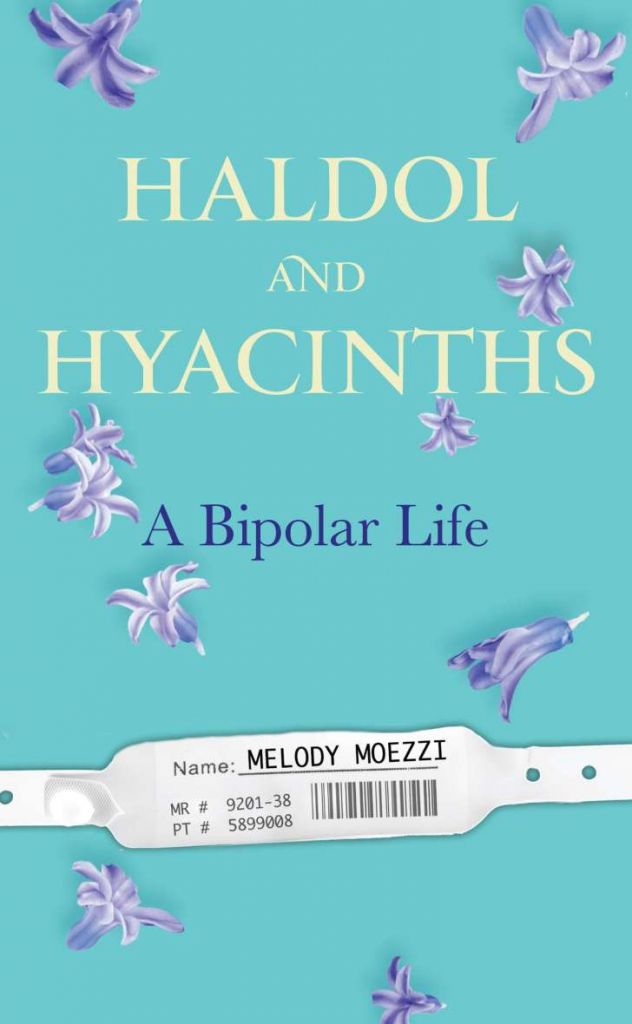

Haldol and Hyacinths

Excerpted from Chapter Five of the memoir Haldol and Hyacinths: A Bipolar Life (AVERY, August 2013)

United by helplessness, fear, fragility and common enemies, the Cottage E residents of November 2005 weren’t much different from those in myriad other residential psychiatric facilities across the country. We were, however, quite extraordinary as compared to our “normal” counterparts on the outside.

There was Compass (I never learned her real name), a middleaged schizophrenic teacher who’d stabbed herself in the jugular with, you guessed it, a compass. To her, I recommended dickies, turtlenecks and antipsychotics.

Then there was Ellie (not the elephant, but a teenaged girl), short for Elham. She was Iranian too and had a wicked case of bulimia. She came to Stillbrook after nearly dying from a ruptured esophagus. Subsequent to her statement that she’d do nothing more than buy a boatload of shoes if she won the lottery, I gave up on Ellie. Plus, she didn’t speak Farsi, so we couldn’t talk behind people’s backs together.

Eating disorders were painfully common within Cottage E. Besides Ellie, there was a thirteen-year-old cheerleader who refused to sit still, terrified she might burn one less calorie (She said she’d start a cheerleading camp if she won the lottery. I told her to eat and trade in cheerleading for debate or a sport with longer skirts and shirts. She declined.); a teenaged binge eater who was always eyeing the anorexics with envy (She said she’d give half her winnings to the Humane Society and spend the other half on a personal chef and trainer. I advised her to eat less and exercise. Being way too polite for her own good, the poor girl thanked me.); and a pregnant bulimic who was trying to stop vomiting to save her baby—forget herself (She’d have socked away her prize money for said baby’s college fund. In an attempt to scare her straight, I suggested she give up her antics, as she could be prosecuted for child endangerment if her baby was born retarded or even manslaughter if it died. She told me not to use the word “retarded.”).

There were a few cutters—most of whom were frequent flyers, refugees who took trips to psych wards the way most people take vacations. I counseled all of them to stop.

Most of the drug addicts boasted a dual diagnosis, as they were often self-medicating an underlying mood disorder: coke, meth or Ritalin for depression; heroin, Vicodin or Percocet for mania. Apparently the drugs work quite well before they rot your teeth, rob you of your life savings, chisel holes in your brain and/or stop your heart. Besides brilliantly advising the addicts to stop as well, I also suggested they refuse to accept there was anything they couldn’t change.

Overall, I couldn’t have given shittier advice had I tried. Still, most of my victims were patient with me, as I wasn’t deliberately nasty, just misguided and delusional.

Of all the other patients at Stillbrook, Rachel troubled me the most. She was always smiling and showering people with compliments, but visibly uncomfortable when any were returned. A lot of the other patients oohed and ahhed at Rachel’s missing eyebrows and eyelashes, not to mention her nearly bald head when it peeked out from under the pink bandanna she wore to conceal it. I expect what distressed me most about Rachel, the reason I didn’t ooh or ahh at the consequences of her compulsion, had to do with the fact that I was intimately acquainted with it. I understood Rachel’s disorder, trichotillomania or “trich,” because I’d dabbled in it as well. While I managed to avoid such extremes, I recognized what it was like to have a bizarre and embarrassing habit that baffled and revolted the general population. My mom, on the other hand, didn’t. Her first response upon meeting Rachel: “Vai, tanks God that never happens to you.”

At thirteen, I began pulling out my eyelashes. I had no idea why I started, and I certainly didn’t expect that it was a real “disorder” with its own name and patient cohort. As far as I was concerned, I was the first person on the planet to pick up this strange and disgusting habit. I tried to hide it, but eventually I couldn’t. When I came to the dinner table one evening looking like an early-stage cancer patient, my parents were appalled. Their solution was no different from the one I’d suggested to so many of my companions at Stillbrook: “Stop.” They threatened to send me to a psychiatrist if I kept it up—an empty threat by all accounts, but effective nonetheless. Undoubtedly repulsed by the unsightly consequences of my new habit, they nevertheless failed to view it as anything more than an unfortunate alternative to nail-biting or hair-twisting.

Thoroughly petrified at the prospect of seeing a psychiatrist at 13, I stopped. This is rare with trich, but given the mild nature of my case and my mounting vanity, I managed to beat the odds—sort of. I still attack my lashes on occasion, usually when I’m particularly nervous. But it’s never been as bad as it was back then, when every day seemed full of new and ever more excruciating humiliations.

There is little in life more anxiety inducing at that age (f**k it, at any age) than being subjected to a shirtless scoliosis test in the girls’ locker room when you’re the only girl in the class who doesn’t wear or need a bra; or wearing shorts in gym class when you’re the only girl in the class not allowed to shave her legs—and bonus, the hairiest of the lot; or being asked if your dad regularly beats you thanks to the untimely release of Not Without My Daughter; or being told to go back to IraQ thanks to Desert Storm. I mean, who wouldn’t start pulling out her eyelashes when faced with such daily degradation? Don’t answer that.

Sure, there are far more devastating fates, but at the time, I was certain there was nothing worse than enduring the seventh grade as a staggeringly skinny, flat-chested brown girl in Ohio, with a budding unibrow and a faint mustache—not to mention a seemingly endless array of unusual lunches intended to fatten me up.

My mom was obsessed with getting me to a more “normal” weight, dragging me to countless specialists, all of whom told her that I was fine despite missing most of my physical “milestones.” Still, she continued stuffing me with kabob, rice, steak, potatoes, various stews, casseroles and sweets. On the weekends, she fed mehaleem (a mixture of barley, wheat, onions, sugar, lamb, butter and God knows what else) or, worse yet, kalleh pacheh (a soup containing an entire lamb’s head, including the tongue, brain, and eyes, feet and a whole series of other segments of the godforsaken creature). Nothing helped. I remained an increasingly hairy, pencil-sized mutant who was force-fed lamb’s brain on the weekends. Again, who wouldn’t start pulling out her eyelashes? Again, don’t answer that.

Still, if only I’d felt compelled to pull out my leg, arm or a few eyebrow hairs instead, I might have saved myself a lot of grief. Thankfully, though, my lashes grew back, and by high school, I’d dropped the habit for the most part, gained a few pounds and picked up a razor.

Repri nted by arrangement with AVERY, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © MELODY MOEZZI, 2013.

nted by arrangement with AVERY, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © MELODY MOEZZI, 2013.

I have been hospitalized so many times that up seems down,back seems forth and right seems wrong.when I was twenty i experienced my first seventy two hour hold and learned what the Thorazine shuffle is.i never personally allowed myself to engage in the therapy offered as being thrown to the wolves so many times i knew it wasn’t worth the effort because lord knows i wouldn’t ever be seeing anyone from where I was again.eventually you wind up where I reside today.forty four on disability trying to deal with PTSD. From multiple hospitalizations and learning what being bi polar 1 is and how I need to manage my life and not let others who have no real intimate knowledge of the pain I have seen in my young life.boundaries where something that where constantly crossed all my life.the more you allow this to happen the less you know where you begin and others end.