Christopher Columbus’s logbook of the Voyage of Discovery of the New World.

Share This

Print This

Email This

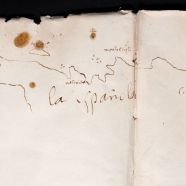

Half-Drawn Hispaniola

In February, I found myself in Nashville with a few hours to kill before my reading at Parnassus Books. It was terribly cold, and weird pellets of slush were pinging off my windshield; I asked the audience that night about the phenomenon, and they told me it was sleet. I felt a renewed gratitude for my New Orleans home. In the midst of this frigid, wet assault, seeking shelter, I made my way to the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, a museum encased in an Art Deco former post office that’s marbled with glamour. The exhibition on display didn’t matter—I just wanted to thaw my toes—but it ended up being quite beautiful, pulling together a private Spanish collection that included works by Goya, Rubens, and Titian. This noble family also owned a folder of Columbiana, documents from those initial expeditions to the Americas in the 1490s: a ship manifest, a decree from Ferdinand and Isabella, and a travel diary from the winter of 1492–93 with a sketch of the northern coastline of Hispaniola.

I hovered over this map for a few moments, then continued around the gallery, gawking at Goya’s Duchess of Alba in White with its hilariously stoic lapdog. But a few minutes later I was standing again at the glass case, peering in. Just a simple sketch. Probably, though not certainly, by Columbus. Probably, though not certainly, the first map of the Americas drawn by a European. I was impressed, against my better judgment. (Where was the first map of Europe drawn by an indigenous American?) The image was captivating because it represented one of those flash points in history after which everything was irrevocably changed. That line in ink, drawn by a single man on a single ship sailing slowly past a coast, was also a line through the heart of the continent. Not a sketch but a garrote.

The map is small, but it takes up two pages of Columbus’s travel diary, as if he misjudged the proportions when he began and ran over the crease in the binding with some chagrin. I can’t help thinking he could have turned the diary 90 degrees and used his white space more efficiently. He may have thought the same. But this was more a placeholder than a piece of art. The line starts around the present-day town of Gaspar Hernandez in the Dominican Republic, then snakes around the bumps in coastline (more prominent here than in actuality) until it rounds the western corner of Haiti and fizzles out near the present-day town of Gonaïves. Columbus is taken with the islands: Île de la Tortue is here (“Tortuga”), but also a cluster of three small islands near Cap-Haitien and a veritable archipelago near the peak of “Monte Cristi”: a larger bean-shaped island and four whimsical satellites, each drawn counterclockwise. He calls the western cape “San Nicolas” and marks a single mainland town: “Natividad,” or Villa de la Navidad, the fort his men built after the Santa María floundered on the reef. He was stuck there three weeks before finally escaping on the Niña. (When he returned a year later, the thirty-nine men he’d left had vanished, the settlement burned to the ground. Archaeologists are still poking around the Haitian coast, searching for the ruins, the Hispanic Roanoke.) In and among the lines representing actual features are eight brown inkblots that exist in a cartographic twilight zone between island and bloodstain. They’re precise enough for the former, and brown and clotty enough to shiver anyone who knows what Columbus brought to the Caribbean. From one of the stains a small cross grows: a sign of faith? A compass rose?

Christopher Columbus’s logbook of the Voyage of Discovery of the New World. Map of La Española (detail), 1492 (?). Paper, covered in parchment, double folio. Dukes of Alba Collection, Columbus Vitrine, Liria Palace, Madrid. Photograph from the Frist Center for the Visual Arts. http://fristcenter.org/calendar/detail/treasures-from-the-house-of-alba-500-years-of-art-and-collecting.

I didn’t know what else was in the diary, and I wasn’t particularly interested; Columbus’s notes didn’t hold any fascination for me. It’s the map that was magnetic. It marked a story that had just begun; the continent’s fate was being outlined—messily, hesitatingly. The fact that the map was unfinished drew the viewer in like a morbid counterfactual. Could things have gone differently? He’s only half there. He’s only so far in. No one knows what comes next.

This map only pops up in a few places when you search online. One is Yale University, on a webpage nestled in their Genocide Studies Program. Another is Southern Methodist University, where it advertises an exhibition on campus “celebrating Columbus Day weekend.” It occurred to me that Columbus is kind of a Southern story, if we embrace our Caribbean neighbors in a shared past. And what do Southerners do if not remember things problematically?

What do we think we’re “celebrating” on Columbus Day? That half-drawn line? The unknown that lures any explorer? The darkness that needs our own enlightened gaze? It’s the impulse behind Manifest Destiny, colonialism, the Apollo missions: white people be conquerin’! Columbus’s partial map is a drawing that invites our participation not only in the thrill of discovery but in the horror of what was to come. On the island of Hispaniola alone, 80 to 90 percent of the Taíno population died within a generation after Columbus’s ships arrived. Some estimates put that at three million souls. As the great navigator bent over the desk in his cabin, tracing out the contours of a foreign land, his men were twisting through the forests, carrying guns and swords and viruses and Christianity and racism. For the Taíno, this was a story of genocide, not celebration. Yale got it right.

But the South, for all its memory problems, has a wealth of stories to draw from; Europeans aren’t the only ones telling us what the world is shaped like. What about early American Indian maps? What do they look like? Circles upon circles upon circles, each linked by umbilical cords. Where Columbus drew a line and abandoned it, that being as far as his own knowledge reached, early maps from Catawbas and Chickasaws show the intricate relations among whole communities. There was no individual; there was no unknown territory. On a Catawba deerskin map from 1721, beyond the circles of towns, the English settlements to the north and south sit on the periphery, represented as squares. “This is our country,” the map implicitly says, “and you are over there.” (In addition to these sociopolitical maps, Native peoples created pictorial facsimiles of their physical environments as accurate as any European’s; Columbus himself encountered a Mayan man in 1502 who could chart sections of the coastline of Honduras.)[1]

West from Hispaniola, at about the same time Columbus was poking around the islands, the Aztecs were engaged in an interdisciplinary mapmaking venture of their own. The Codex Xolotl shows not just the mountains and rivers of the region, but its history: the arrival of the Chichimecs to Mexico, their exploratory jaunts through the terrain, and all the intricate dramas of a people in migration. There are speech bubbles, flipbooks of action, secondary plots. These maps are very much alive; the Aztecs had no interest in creating a static record of an unchanging natural world.

Maps reveal what a person, and the culture looming behind that person, thinks is important. Columbus wanted a precise rendering of Hispaniola’s coastline, as far as his pen could reach. Why? So he knew where to land, how to retrace settlements, what he could claim. The Catawbas wanted a holistic picture of the peoples of the South; they needed to know where their friends and enemies stood, along what lines resources could be shared or traded, what a Catawba identity meant in a region of many identities. The Aztecs recounted a conquering history in order to legitimize their enduring presence in Mexico, link the people with the land, and shape communal memory. The indigenous mapmaking of the Americas tended to prize stories over data, a sense of fullness and completeness rather than the line that trails off because the individual’s knowledge comes to an end.

And I, as an individual, standing over a glass case in an old post office to escape the sleet of downtown Nashville—what did I need directions for?

I don’t travel as much as I’d like. As a writer, I tend to be fairly stationary. Maps to me are games for the imagination: alternate worlds, a different set of eyes, might-have-beens. I imagine myself a tiny ink person traveling along this wiggly ink coastline—at a certain point, I fall off, like people told Columbus he would. His line takes me to the Caribbean. A map that depicts a location. His messy inkblots carry me to the cabin of his ship. A map of a man’s body, the upset of his stomach, his shaky hands, a whispered “mierda!” His looped labels—“Natividad,” “Monte Cristi”—funnel me inside his brain: a map of the conqueror’s hubris, a last flashing attempt at Civilization before the ignorance and cruelty of his own people eradicate an entire culture, all those alternate maps destroyed before they could even be drawn.

I left the glass case and retreated to the far side of the gallery, where I pretended to look at a portrait of a woman in flounces while I watched the other patrons glide past the Columbiana display. Most glanced in the case for a second, scanning. Some, uninterested in pieces of paper, walked on by. One man stared for quite a while, then gestured excitedly to his wife: “Honey! Come check this out!” Could I blame him? I, too, hadn’t been able to look away.

[1] Gregory A. Waselkov, “Indian Maps of the Colonial Southeast,” Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, rev. ed., ed. Gregory A. Waselkov, Peter H. Wood, M. Thomas Hatley (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2006). See also Mary Elizabeth Fitts, “Mapping Catawba Coalescence,” North Carolina Archaeology 55 (2006): 1–59.

And maps are supposed to be objective in the picture they present. This reminds us that we view a map in the way we view anything created by human beings, with our own subjective story, experience, values, and general perspective. A map can turn out to be a blank sheet of lines and information inviting us to enter into an experience of our version of history, art, literature — life.