House Lives, No. 4 by Laura Frankstone, part of the series dedicated to Cecelia

Share This

Print This

Email This

House Lives: An Art of Love and Grief

On September 26, 2022, the past tense blew my world apart. Three thousand miles from home I was awakened to be told that Cecelia was dead. My beautiful, brilliant, deeply cherished daughter had taken her own life, while I was far away and sleeping. This was horrific, a loss so searing and so vast, I was unable to breathe. How could it be that I would never see her again, hold her again, talk with her again, be with her again in the present tense?

From her birth, Cecelia, like her older sister Kate, had been a star, a light in the world and in my heart. She was a supremely gifted painter and designer, a fluent speaker in six languages, a world traveler, curious about everything.

Cecelia and I had much in common. Not only were we both artists, we shared a deep wanderlust. She and I traveled together throughout Europe and the United States and it was she who introduced me to Norway and Sweden, the luminous Scandinavian world, which I loved immediately.

Cecelia was, simply, a glorious human being. It has been the highest calling for me to be the mother of my two girls and I have given them every ounce of love and care I have. Surely, surely, this news of Cecelia was the cruelest nightmare of my life; surely I would awaken from it, fall to my knees, and sob with gratitude and relief.

Over time and with the words of her careful suicide note shedding light on her heartbreaking decision, it became clear that Cecelia had been suffering from intermittent periods of depression, the velocity and depth of which I could not have fathomed. Though it had been over fifteen years since she lived at home, we talked almost every day on the phone. I knew she had spells of depression, as both sides of our family do, but we often talked at such times and she was always able to ride them out. I had no awareness of how skillful she had become at hiding her darkest times. And it was that darkness that stole her from life and stole the light from mine.

Still now, almost three years later, I weep when I write the words, “Cecelia’s death.”

Love and support and condolences came immediately from family and friends all over the world. Cecelia was greatly admired by those who knew of her, beloved by those who knew her best. My community of Hillsborough wrapped us in their loving arms then and continues to do so.

There is such a thing as “grief brain,” and I was living it. I was numb when I wasn’t crying, confused, lost, emotionally naked, desperate at times, and angry.

I had no choice but to go on with my own life the best way I could. I had every reason to do so. My surviving daughter, Kate, my husband, my grandchildren, and my stepchildren needed me.

And then, a book I received from two separate friends, friends on both coasts, showed me a way to begin to move forward while living with unspeakable loss.

The Dark Interval: Letters on Loss, Grief and Transformation by Rainer Maria Rilke, the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German poet, is by far the most original and profound book on grief that I have read. Rilke addresses all aspects of grief and death in the letters he wrote to his friends in mourning.

The passages below were particularly revelatory for me:

But as to the influence of the death of someone near to those he leaves behind, it has long seemed to me that this ought to be no other than a higher responsibility. Does the person who passes away not leave all the things he had begun in hundreds of ways to be continued by those who outlive him, if they had shared any kind of inner bond at all? (xviii)

You must . . . this is the task that this incomprehensible fate imposes upon you, you must continue his life inside of yours insofar as it was unfinished, his life has now passed onto yours. You, who quite truly knew him, can quite truly continue in his spirit and on his path. (14)

Rilke’s exhortation to carry forward the work of the lost loved one struck me hard and gave me a desperately needed sense of purpose. Because we are both artists, I can carry my daughter’s work forward in a way not available to others living with traumatic loss. Although Cecelia and I worked in different ways and for mostly different purposes, there is a genetic connection stylistically, especially in our drawings, less obviously so in our painting, but there, nevertheless.

Cecelia’s art career involved painting gorgeous bespoke murals and designing wallpaper for clients in New York, Palm Beach, and New Orleans, among other places. Floral imagery was her specialty. This was an exciting but very stressful career, especially when the pandemic made fulfilling commissions at clients’ houses difficult. She needed to establish an income source that was somewhat reliable and this was hard in such a career, especially at such a time.

I have painted for many years, but not for the kind of client and under the same pressure as Cecelia’s work entailed. Floral imagery for me was mostly confined to sketches of gardens, including my own, or places I traveled.

Rilke’s book gave me the idea to engage in a collaboration with Cecelia, to create a series of paintings with her spirit, with the energy of her life and work, with my love for her. I would start this project by using her images and her color palettes, but I would paint in my own gestural, more abstract style. I would start with peonies, her favorite flower, and I would use a palette of pinks, her favorite color, her spirit color. It was a leap for me to paint flowers in a way that was relatively realistic in terms of the conveying of volume and mass. This had never been a goal of mine and when I struggled to paint my first pink peony in the first of my series devoted to Cecelia, I could clearly hear her say, “Mama, that is adorable,” in a voice that was loving and slightly amused. She herself was a master at painting perfect peonies.

- Cecelia’s gorgeous peony wallpaper

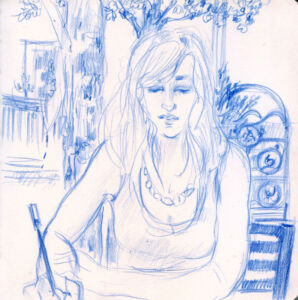

- House Lives, No. 4 by Laura Frankstone, part of the series dedicated to Cecelia

With this project, I felt that the deep connection I had with my daughter was not completely lost. Not only would this work be of her and about her, but it would to a great extent mend the tragic severing of our intense emotional bond.

Along with flowers, the central image of a house emerged spontaneously in the work, superimposed on a ground of open space around which her flowers would float. It was an emotionally important symbol and it also served a valuable aesthetic purpose. The geometric simplicity and purity of the house shape was a powerful counterpoint to the loose, organic shapes of the floral imagery.

The notion of house/home was deeply important to Cecelia and to me. This manifested in our lives in different ways. When my girls were little, we loved to ride around town looking at houses, trying to imagine the lives of the people who lived there. I had a sizable collection of books on home decor and both girls spent hours poring over them. With this early interest, it is no surprise that she chose as her profession the beautification of house interiors.

My experience of house and home was different. Because my father was in the Air Force, my family moved often, frequently after only a year, to the next place he was posted. In those years of midchildhood, I made my little brother sit down at the kitchen table with me so we could draw what we thought our next house would look like. I needed this, needed to know there would be another place for us.

Cecelia also moved house often, but as an adult. Her search for the right place for her restless spirit to take root was never to be finished.

Cecelia sketching in Asheville in the summer of 2021. We were there for the 40th birthday of her sister Kate. I often drew her drawing.

As I write this, I am struck with the realization of what I am saying in this painting series. The house shape in the paintings, fragile, primal, transparent though it is, is my way of trying to provide safety for my precious daughter, a home for her spirit. It is the house I have been imagining all my life, a kind of womb, a place of protection and comfort.

I have completed almost nine paintings in my series and I have no plans to quit soon. The shifts in tone and nuance of my grief are evident in the works, as you would expect, in their changing colors, compositions, mood. The rhythm of change is erratic, just as is the nature of grief, new every day.

The rectangle of the painted surface, and within it, the rectangle of that ethereal house, create a space where Cecelia and I are together again, surrounded by love and beauty, in the past, present, and future.

Cecilia

Laura. I think you would have found this path through the wilderness even without Rilke, but what a North Light to follow just when you needed it most. And now here you are in radient collaboration with Cecelia, to be that light for others. This is a gift.

Thank you, my dear friend. You are right that the light came at just the right time.

And isn’t it perfect that the Rilke book came from Jeffery and Rafael within days of each other. I am moved by your comment.

Thank you for continuing your artistic conversation with your daughter. May it continue to bring experimentation, creativity and maybe even solace.

Thank you, Pier, for your kind and thoughtful comment. This “conversation with my daughter,” as you beautifully put it, is saving me.

What a beautiful, direct way you have of translating into words what your deep process is in images first. Thank you!

Thank you very much, dear Francesca, friend and neighbor.

What a beautiful way you have of translating into words what your deep process is in images first. Thank you!

Laura, your tragic journey has become a beautiful one in your collaboration with Cecilia, even more so with your willingness to share it here. I pray that your grief, like mine, becomes softer. . . and that you continue to feel her very real presence in the love that lives on, and the tender work that you share.

Jo Ann, thank you so much for writing. Of all things in life I wish we didn’t share, our devastating losses are paramount. I am very eager to get up to Blowing Rock to meet you and take a hike together with Elizabeth, among other things. Thank you again for your comment full of compassion and understanding.

Yes and yes to all of the comments above, Laura. Thank you for this beautiful expression of your painful, healing journey after such an unfathomable loss.

Thank you, dear Sally, for you kind and supportive words. Writing helps me. Painting in collaboration with my precious daughter’s spirit and in her honor saves me.

Sadly, I share your experience. Although my son did not commit suicide, but rather he was murdered. He was a wonderful and caring young man. Strangely, he had a premonition that he would die young and told this to a friend. He. said that his mother would write a book and that he would have a chapter in it. I did write a book, but the sorrow never leaves.

Dear Gabriele, I am so deeply sorry that you lost your beloved son so tragically. It is left to us to find a way to live our lives after experiencing the worst thing that could happen to a parent. I send you my heartfelt condolences.

Laura, such profound narrative transforming your loss, co-creating new works with your Cecilia. PaInfully moving but full of devotion and hope.

Thank you for sharing your heart, honoring and celebrating the deep love-bond you have with her.

And those peonies… the life and movement they gives us ! Thank you

Dear Rafael. Thank you for being the loving and compassionate friend you have been for so long. 🩷🩷🩷🩷