Inspired by Ex-Wife

Stumbling into the Pages of Ex-Wife, Marsha Gordon

When I first saw the name Ursula Parrott on the cover of an unproduced MGM screenplay draft written by F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1938, I had no idea who she was. All I could deduce from this initial, brief encounter was that she had written a story that bore the intriguing title “Infidelity,” that the celebrated novelist Fitzgerald was hired to adapt it for the screen, and that she had a fantastic name. The internet revealed some scraps of information: she was from Boston, she was a writer, someone had written an MA thesis about her in the late 1990s, and she had died decades before (in 1957 to be precise).

I found that none of Parrott’s books were in print, so I bought a used copy of the 1989 Plume reprint of her first novel, Ex-Wife—the only book of hers that had ever been republished. It arrived in the mail a few days later and changed my life.

“My husband left me four years ago. Why—I don’t precisely understand, and never did. Nor, I suspect, does he.”

Those catchy, confessional first sentences of Parrott’s largely autobiographical debut novel—so frank and succinct, so achingly glib, so crisp and modern—drew me into a single- sitting-read, cover to cover. I devoured that copy of Ex-Wife not just once but twice that week, sure that I had stumbled into a fascinating writer’s pages but not knowing that I would end up spending the next few years of my life reading every word she ever published or wrote that I could get my hands on, researching her life, and writing her biography.

Ex-Wife—which, thankfully, is now back in print in the US and UK with translations available in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Poland, France, Sweden, and Germany—is at its core the story of a woman whose marriage has failed, infused with all of the sadness, anger, blame, and regret that goes along with it. The novel has some of the best descriptions of life in New York City in the 1920s that I’ve ever read. It also has Sex in the City vibes, as many young women told me during my book tour when they also expressed their amazement that they had not been assigned this book to read in high school or college. Ex-Wife, in fact, brilliantly describes women’s lives at this time—their work, living arrangements, and conversations among girlfriends; their clothing and the cocktails they drank and where they consumed them and what too many of them could lead to.

But underneath the martinis and blue velvet is a mournful book about a young, hopeful marriage and its tragic undoing. As many of the book’s reviewers in 1929 noted, it seems that modernity and its excesses are to blame for the demise of Patricia and Peter’s nuptials. Feminism, too, has its share of the blame, which Radcliffe-educated Parrott benefitted from even as she dared to probe the movement’s unintended consequences for her generation. “Ex-wives . . . young and handsome ex-wives like us,” Pat tells her similarly de-husbanded girlfriend Lucia, “illustrate how this freedom for women turned out to be God’s greatest gift to men.” “We are free, Applesauce!” Lucia later scoffs in the sarcastic patois of her times. “Free to pay our own rent, and buy our own clothes, and put up with the eccentricities of three to eight men who have authority over us in business, instead of having to please just one husband.”

Touché!

As I read Ex-Wife those first two times, I was struck by the way that Parrott’s novel explicitly indicted male characters—most of whom derived, in one way or another, from real men in Parrott’s life, as I would later learn. The novel itemizes and dramatizes their bad and maddening behavior. Don’t get me wrong: this is not just a male bashing book, nor is it merely an airing of Parrott’s personal grievances. But it is a flashlight shining in the dark corners of Jazz Age New York City life, a cautionary tale that was often misunderstood at the time as a shallow and flippant celebration of hedonism. In fact, the novel depicts its male characters’ moral hypocrisy and double standards (the root cause of the novel’s titular divorce), potential for brutality (verbal, physical, as well as sexual), and callous, predatory behavior. I read Ex-Wife as a warning penned for women of her generation, written by a woman who had lived almost every awful incident in its pages.

What really fascinated me, though, was that instead of just accepting or dwelling on their hurts and traumas, Ex-Wife’s female characters were possessed of a tenacious capacity for reinvention and survival. That was really the moral to this scotch-soaked story: get ready for the bumpy ride of modern life and don’t worry, ladies, you can handle even the worst parts of it. Patricia navigates her way through a hurtful and loss-filled marriage, a divorce she doesn’t want to go through with, supporting herself financially, surviving both an abortion and a brutal rape, and many other hurdles large and small. But Pat puts one nicely heeled foot in front of the other and carries on.

Although I don’t care much for the novel’s not-quite-happy and definitely-too-tidy ending, which takes the form of Pat’s dispassionate, practical second marriage, I know enough now about Parrott’s sense of realism and cynicism to think it was likely suggested or imposed by the publisher, perhaps in the same way that the Academy Award–winning 1930 film adaptation, The Divorcee, had its original sin remarriage ending foisted on it (MGM’s penchant for concluding their sinful stories with a traipse down the aisle nicely aligned Hollywood’s ascending culture of moral policing).

“It is not true that, in time, one ‘gets over’ almost anything,” muses Patricia toward the end of Ex-Wife. “In time, one survives almost anything. There is a distinction.”

Parrott’s first novel is filled with many such poetic and moving insights, which a reader or reviewer might be forgiven for missing if they are looking for the next taxicab grope or negligee description. On my second read, I noticed the way that Parrott uses parentheses in the novel to express any un-modern feelings that her female characters are too embarrassed to express—fear, longing, and disappointment, for example. But Patricia’s clarifying explanation about the difference between “getting over” something and “surviving” it doesn’t suppress or conceal the truth. Here she details a fact of life, earned honestly by its author. I’m certain that Ursula Parrott herself persisted by exorcizing her demons on the page, as she does so beautifully in Ex-Wife.

I am moved by Ursula Parrott’s literary courage, by her decision to bare the hurts and perceived failures of her young life (she was thirty when the book was published, which seems young to me but she considered it a rather advanced age), which she so thinly disguises in Patricia’s tale. Looking at that used copy of Ex-Wife now, with its front and back cover long-liberated from the book’s pages from overuse, I see that I made five handwritten notations in the front matter after I read it for the first time: divorce, infidelity, abortion, freedom, and women’s work. What impressed me then continues to impress me, and other readers, now. This is a novel that, for reasons both understandable and not, remains relevant today. I feel fortunate to have stumbled across it the way that I did, and that others can now come by it more easily.

Ursula’s Rhapsody Anew, Andrea Edith Moore

When I attended Marsha Gordon’s book release event in the spring of 2023, the subject was totally unfamiliar to me: a writer I had never heard of named Ursula Parrott.

Marsha had done the discovery, the research, the writing—the heavy lifting for the rest of us. I had the distinct advantage of encountering Ursula Parrott almost in reverse, beginning not with her books but with her life story. My first “meet-cute” with Ursula came at that very launch, when Marsha paired her talk with a screening of the 1930 film The Divorcee. It was a star vehicle for Norma Shearer, who won her sole Academy Award for the leading role. The film was based on Parrott’s novel Ex-Wife, published anonymously just a year earlier—a bestseller transformed into a Hollywood version for the silver screen.

This screening, paired with Marsha’s fascinating lecture at the Cary Theater, led me to buy my copy of her comprehensive biography Becoming the Ex-Wife: The Unconventional Life & Forgotten Writings of Ursula Parrott. When I read it, it became clear to me that Marsha had unearthed a paragon of the Jazz Age with her own story of cinematic, no, operatic proportions.

And then I finally read Ex-Wife. I was floored. Quote after quote, page after page, Parrott lured me into her world. Her insights about 1920s womanhood, love, work, and social expectations felt astonishingly modern and fresh. I kept asking myself how it was possible that she—and this book—had vanished from the literary canon. This should really be taught instead of, or at least alongside, The Great Gatsby, I repeatedly muttered as I read.

The most inspiring chapter for me comes about two-thirds of the way into Parrott’s tale of a woman’s divorce, work, and dating life in the 1920s. Ursula Parrott’s fantastic writing abilities were matched by a clear musical literacy and the capacity to pace a scene with rhythm and tempo as exacting as the music of George Gershwin she chose to weave into her debut novel. The musical mood of this chapter portrays the leitmotifs of urban life as Patricia, the novel’s impending divorcée, embarks on a twenty-four-hour day-in-the-life episode that reads like a Hollywood film.

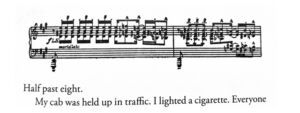

From the very first paragraphs of this chapter, Parrott establishes her method: Gershwin is the clock and the score, the emotional barometer. On the hour, the reader sees, and thus “hears,” printed measures of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924), which are embedded throughout the chapter’s text and lifted directly from the plates of the original score. Parrott treats Gershwin’s main themes like the canonical offices of daily life, giving her chapter the feel of a liturgy for the modern girl’s new way of living in the cacophony and wonderful chaos of a city like New York. Instead of matins, lauds, and vespers, Patricia has taxis, the office in which she works, the Ritz, and after-hours cocktails, each illuminated by snippets of Gershwin’s score. The result is a pitch-perfect response to modernity itself: witty, musically sophisticated, and unapologetically female.

“Sam gave Lucia an Orthophonic Phonograph for a birthday present.

Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ was almost the only record we ever played on it.”

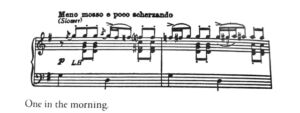

The chapter begins with a literal fanfare. Parrott inserts the opening bars of the Rhapsody’s “Ritornello”

as if to wake her reader with “Pat” herself, summoning her downstairs for coffee with her housemate Lucia at seven in the morning. This “Reveille” signals the start of a new day by way of the modern technology that enabled listening to music at home, while also underscoring the coffee klatsch about the night before and Lucia’s impending engagement to an undazzling but wealthy and more faithful older man (which is to say a sure bet).

“The tune matches New York… it has gaiety and colour and irrelevancy and futility and glamour as beautifully blended as the ingredients in crêpes Suzette . . .

It makes me think I’m twenty years old and on the way to owning the city,” Lucia said. “Start it over again, will you?”

At eight in the morning, after cold cream, stockings, earrings, and handbags, the “Train” motif from the Rhapsody propels Patricia into motion, not by train, but by taxi through New York’s crowded streets and on the way to her job in a copywriting office.

Once at work, she mentors her young protégée, a toiling copywriter torn between the urge to keep working or give up the independent life she loves as a young writer in order to get married—which she confesses that she probably will do.

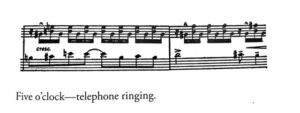

After work and back at home, the 5 o’clock music “Stride” rings in a jaunty and improvisational telephone call that results in an impromptu dinner invitation.

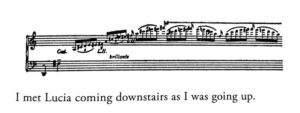

Pat accepts a cocktail date at Giacomo’s bar in lieu of supper due to later dinner plans with a famous painter. What follows is a cascade of “Clover Clubs cold as ice cream and pink as fingernail salve.” By the time Pat is ready to return home to freshen up for her dinner date, Gershwin’s chromatic scales notate her tipsy stumbling up the stairs (note that scale is the Italian word for stair, something the Radcliffe-educated Parrott was likely to know by way of her Latin studies) while Lucia drifts downward in counterpoint, a marvelously literal form of text-painting.

The chapter’s wit sparkles in the roommates’ banter on the staircase. Lucia floatingly muses that great lovers are like musicians who take one lesson on every instrument but can play none of them. From below she delivers the prophetic punchline before Pat’s date with the supposed Cassanova painter —“He couldn’t play a tune on any of them in the end, Pat.” Parrott punctuates the bitingly accurate remark with three full measures of the Rhapsody’s Full Orchestral “Ritornello” at top speed and laughing.

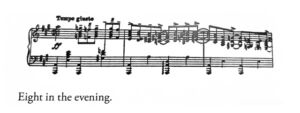

As Pat dines and dances at the Ritz, the score modulates again. Parrott marks the painter’s endless monologues about art and women with the “Scherzando,” a theme that slyly undercuts his bluster. The music follows them home, where the evening reaches its absurd climax: her date offers Pat the beautiful maple lowboy she admired in exchange for her company, quid pro quo. But he’s chased off by Pat’s friend Kenneth, who bursts from the bathroom, declaring himself to be her manager.

The scene unfolds like a farce, and Parrott’s clever use of the musical marking Scherzando—“jokingly”—underscores Pat’s rescue by yet another man. But at a deeper level, Parrott also seems to ask: is the joke still on the woman? Do the same social constraints that once held women back still play tricks on us as we step into new roles?

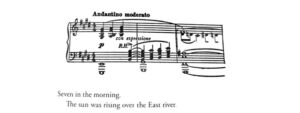

Parrott closes this day with Gershwin’s love theme at sunrise. After a “gargantuan dinner,” too many drinks, and her one-night-stand escape, Pat and her rescuer Kenneth walk together by the East River as the music softens. The twenty-four-hour liturgy closes with a poetic “Amen,” an exhale from the bright blast of the “Ritornello” resolves into tenderness— the beauty of the city and these friends both exhausted yet renewed by Kenneth’s poetic reading of Swinburne:

From too much love of living—

From hope and fear set free

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever Gods there be

That no life lives forever—

Indeed, one of the astounding things about this book is the way it shows the exhausting pace of modern life for working women in the city. In this one chapter, Parrott does more than borrow Gershwin—she conducts him. She treats the Rhapsody as both metronome and mirror, calibrating her narrative against the rhythms of modernity. The chapter is not just about a divorcée’s day. It is about how music, literature, and city life interpenetrate and how the Jazz Age demanded new forms to capture its distinctly forward-moving American tempo, and for Ursula, especially, in the changing lives of women.

Ursula, A Musical Portrait

As is evident from our individual contributions, we find much to admire in Ex-Wife and are equally fascinated by the life of its author. So much so, in fact, that we have begun collaborating on Ursula, a musical melodrama that will bring Parrott’s words to life. Blending music, text, and archival visuals, this new work will illuminate Parrott’s life, philosophies of modern living, and literary contributions set against the backdrop of the Jazz Age.

Drawing on both Parrott’s published and personal writings, Ursula will not only tell her story but also capture the power of her first novel through music and lyrics infused with the spirit of her time and place. We will collaborate with a contemporary female composer to develop and write a new theatrical work for soprano and chamber music ensemble that highlights Ursula’s world in the vibrant musical colors evocative of the Jazz Age. Our goal is to premiere this work with opera companies and chamber festivals in 2029 to mark the 100th anniversary of the publication of Ex-Wife.

While our point of departure is Parrott’s 1929 bestseller, with George Gershwin as a cultural and sonic touchstone, we also trace her era through another overlooked and parallel female figure of her time: the prodigy composer Dana Suesse. Though celebrated in her lifetime, like Parrott, Suesse has also slipped into obscurity. A 1932 recording of her Jazz Nocturne brought her to the attention of bandleader Paul Whiteman, who had famously premiered Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue eight years earlier. At her publisher’s urging, Suesse composed her own jazz piano concerto in just ten days and auditioned for Whiteman in Chicago. Impressed, he featured her in his “Fourth Experiment in Modern Music,” where she premiered her Concerto in Three Rhythms at Carnegie Hall on November 4, 1932, as piano soloist with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. In their December 8, 1833, issue, published when Suisse was “only 21,” the New Yorker called her “the girl Gershwin” for her rare ability to move between Tin Pan Alley and the concert stage.

As an initial foray into the project, Marsha and I fused these two forgotten women of the Jazz Age and adapted one of Suesse’s melodies, My Silent Love (1932) with lyrics drawn from Parrott’s prose. We created a scene about Ursula’s relentless struggles with debt and overspending, rendered in the musical language of the period. The lyrics, all taken from Parrott’s personal writing and adapted into the song, include the following verse:

Excerpt from: Ready Cash, sung to the tune of My Silent Love

My Dear Mr. Bye,

Intro:

Seven in the morning,

I feel I owe you—

An explanation of myself.

One of those Great Tragedies

That may be traced in

The plots, and which seem to punctuate,

The lives of female authors . . .

Verse:

How am I off for ready cash?

No more extravagant clothes!

But just stake me to this month?

How am I off for ready cash?

Could use a hundred or two

If you could mail it [direct]

Of my two virtues

One, I never cry

Over split milk,

Right, my dear Mr. Bye?

Ursula may yet again be herself

At five minutes past the twelfth

Who can tell?

How am I off?

How am I off?

How am I off for ready cash?

This excerpt from our work in progress demonstrates our methodological approach for this project: telling Ursula’s story through the creative re-ordering and contextualizing of her own words. Set to the rhythms and tunes of her era, in this case to music written by another tremendously successful woman, Ursula will use Parrott’s unique combination of wit, skill, honesty, and personal drama to capture her spirited, unconventional life and times, and to celebrate the contributions of modern women to this era of popular American culture.

Note: On January 18, 2026, Marsha and Andrea will hold an event at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Hillsborough, North Carolina, to speak more about Ursula Parrott’s life, writings, and films, and also share their progress on this project.