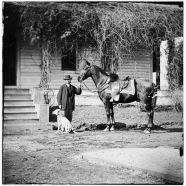

City Point, Virginia. Gen. Rufus Ingalls’ horse and dog. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Share This

Print This

Email This

Interview

South Writ Large interviewed Dr. Earl J. Hess about his new book, Animal Histories of the Civil War Era.

Your new book, Animal Histories of the Civil War Era, reveals the importance of different kinds of animals throughout the Civil War. Could you tell our readers what prompted you to organize and edit a volume on this unique topic?

I have always been interested in animals, having grown up on a farm, and my wife and I have always loved wildlife. But I had never thought to incorporate the topic into my scholarship until the rise of animal history began to become prominent. A short article by Susan Nance, “Animal History: The Final Frontier?,” published in American Historian in November 2015, alerted me to the possibilities of applying this concept to the Civil War. Three years later my wife and I attended a panel on animals in the Civil War organized by Joan Cashin for the Southern Historical Association annual conference and I decided then to push forward with an anthology, inviting the presenters at that panel and recruiting others to take part as well.

Why do you think the history of animals has been largely overlooked by scholars of the Civil War?

I think the primary reason is the relative lack of an interdisciplinary awareness among Civil War historians. I am sure they are not taught to think of cross-disciplinary reach in graduate school and there is little incentive to learn it after they become established as professors. Other disciplines, such as archaeology, and even sub-specialties of history, such as animal history, emphasize the value of interdisciplinary thinking. But most historians are not exposed to the idea. That is too bad because cross-disciplinary research has the possibility to greatly enrich our scholarship. Another reason may be that people in general tend to think only about humans affected by war rather than the other sentient creatures that inhabit the earth.

Which animal story within the book would most surprise readers?

That is not easy to answer, but I think the more surprising stories would be the varied interactions with many different types of wildlife, discussed in my essay on that subject; the ruthless use of dogs to suppress slaves and freed Blacks, discussed in Joan Cashin’s and Lorien Foote’s essays; how camels became intertwined in efforts to spread slavery before the war, which appears in Michael Woods’s essay; and the concept of animal agency, the idea that animals can have opportunity to shape the contours of their lives within the human sphere of action, discussed in my essay on artillery horses.

To what extent did the use of animals like horses and mules contribute to the military strength of the Union or Confederate armies?

Very soon after warfare first developed thousands of years ago, horses and mules became an integral part of military affairs. The military strength of both armies in the Civil War would have been almost neutralized without horses and mules. There would have been no cavalry arm of the army; no food for the foot soldiers (because mules pulled supply wagons), no field artillery (because horses pulled it). Also, without horses, officers would have had to walk. They could not have traveled quickly, as they did on horseback, to survey the terrain and maintain contact with far-flung units. David Gerleman’s and Abraham Gibson’s essays deal with the important role played by equines in the war effort.

Did animals shape the contours and influence the character of the Civil War?

Yes, animals shaped the Civil War in many ways that have typically not been appreciated in the past. The introduction of railroads and steamboats did not lessen the significance of horses and mules for army mobility. Any movement away from rail lines and rivers was solely dependent on animal power. An army could not project itself into enemy territory without adequate numbers of draft animals. Also, animals as food had a profound effect on the character of the Civil War. The army ration was heavy on meat, and the desire for a meat-based diet was strong among the young men in both armies, as discussed in my essay on meat-eating and the vegetarian perspective on army food in the war. This unbalanced diet made a number of soldiers pine for vegetables and fruits; worse, it led to many horrible diseases such as scurvy. Jason Phillips’s essay also deals with this topic as it relates to hogs. The Civil War created a huge demand for beef and pork that led to the depletion of farm animals in the theater of war and in many areas of the North as well. Fighting to gain access to resources of food became a major feature of the conflict. In a wholly different area, pets and mascots were widespread throughout both Union and Confederate armies, offering comfort, companionship, and a source of unit pride. Those pets included dogs, squirrels, raccoons, and various birds, the most famous of which was Old Abe, the bald eagle mascot of the 8th Wisconsin. These pets and mascots attained veteran status after the war as they were remembered and commemorated by human veterans, as discussed in Brian Matthew Jordan’s essay. From companion animals to masses of horses and mules, animals in effect became warriors in the Civil War. Some of them, such as artillery and cavalry horses, were trained as rigorously as were soldiers. Sometimes dogs were literally weaponized—used by a few Confederate units in battle or as sentinels.

Can you tell us about your central findings in your fascinating chapter on wildlife during the Civil War?

I had been struck while reading the literature on animal history that no one wrote about wildlife except as symbols (for example, wolves). That is an important take on wildlife. Mark Smith’s essay on bees in my book surveys how they were used as metaphors for battle and for industrial societies at war by contemporaries of the Civil War.

In addition to the symbolic interpretation, we should be aware that warfare greatly affected wildlife and that wild creatures affected the soldiers as well. In fact, the most important point of my essay is to help us become aware that wild animals of all kinds share the earth with us and are involved in our wars without meaning to be. Soldiers experienced actual contact with wild creatures. They lived and worked in the outdoors, dealing with deer, rabbits, raccoons, alligators, and insects. It really changes one’s perspective to realize that many wild animals and insects see us as sources of food for themselves. The ideal Civil War campaigning season, late spring and early summer, happens to be the peak time of the year for the proliferation of many insects that prey on humans, and that is when soldiers invaded their habitat and slept on the leaf clutter that was their home. Of course, soldiers sometimes hunted and fished to supplement their army ration and in doing so encroached upon wildlife. Battles fought in heavily wooded areas severely disrupted the lives of wild creatures living in that environment, leading to the unintended death of many of them.

Did African Americans share in the animal culture of the Civil War era?

The animal culture of the South was multiracial and this anthology deals with race and culture in several essays. Daniel Vandersommers’s piece on congressional discussion concerning the creation of a national zoo after the war shows how references to animals created humor and sectional rhetoric that mirrored the sectional and racial divisions that had been created by slavery, war, and Reconstruction. Paula Tarankow’s essay discusses a former slave who trained a remarkable show horse called Beautiful Jim Key and whose career navigated around and through racial barriers in post–Civil War America. African Americans did share in the animal culture of the era, both as slaves and as freed people. They kept dogs for many of the same reasons as whites, for companionship and to supplement their diet through hunting. It is tragically ironic that in other ways African Americans became the victims of dogs, which were used by the white power structure to enforce slavery. In particular, the infamous bloodhounds of the slave South were used to track down runaways. During the Civil War, Union soldiers came to detest these dogs and killed them as a matter of course when encountering them on plantations. But when animals were not used as coercive agents, the animal culture of the South was remarkably shared across racial lines in the Civil War era.

What was your favorite part of the experience of editing this wonderful volume?

The best part was working with ten top scholars in the fields of Civil War and Animal History on an anthology that was very timely in terms of introducing an important new perspective on Civil War scholarship. These aspects made editing this volume a rare joy.

Are animals an important part of your own life?

My wife and I very much enjoy the role that wildlife plays in our life. We have woods in the back and on the side of our house, a small backyard, and a cove across the street. We have always kept the outside as a wildlife-friendly space, which means no chemicals, encouraging wild grasses and wildflowers, trees and plants with berries, and a well-filled birdbath. With a kitchen dining area that has lots of big windows we are treated to a cavalcade of animals, including deer, rabbits, squirrels, chipmunks, and groundhogs. In the warmer months we enjoy butterflies and hummingbirds during the day and watch fireflies and listen to tree frogs at dusk. In the cooler months we hear owls hooting at dawn and see foxes during the day. Throughout the year, a variety of birds honor us with their presence and birdsong, including mockingbirds, woodpeckers, finches, bluebirds, turtle doves, robins, wrens, chickadees, and cardinals. On the cove in front of the house we enjoy watching herons, ospreys, geese, and ducks. Every wildlife sighting or sound is a special gift for us.

Might you have any new research projects in the pipeline?

I have long worked on several projects simultaneously and especially so since I retired from teaching two years ago. Current projects include a study of camp sanitation and preventive health care in the Union army, and another study on food and hunger in the Civil War.