Bath in The Light. Photo by Martin Gommel. https://tinyurl.com/2p84sdpc

Share This

Print This

Email This

The Edward Tales: Introduction

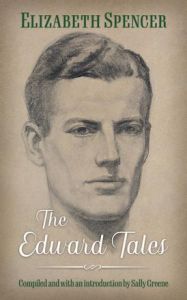

Excerpt from the Introduction by Sally Greene to The Edward Tales by Elizabeth Spencer, compiled and with an introduction by Sally Greene, University Press of Mississippi. Forthcoming Spring 2022.

Lee Smith once got drunk on Elizabeth Spencer. It was the mid-1960s, and she was a student in the writing program at Hollins College. Beer and “besottedness” with this writer who seemed to have pierced her own inner being fueled her drive from Roanoke, Virginia, to Ship Island, Mississippi, some eight hundred miles due south. “It took me a long time to get there,” she recalls. “All I did then was just sit on the beach feeling awful and looking out at the flat, shallow Gulf which turned out to be somehow exactly the way I’d thought it would be. I didn’t even go out to Ship Island. I didn’t have to; the point was the trip. It was a pilgrimage.”

Two features characteristic of Spencer’s work inspired Smith’s impulsive response. The first is the psychological precision with which she conveys the inner lives of her characters, particularly her women. She “articulated my own feelings,” Smith recalled, feelings that were “often dark, inchoate, and scary.” The second, which alone might have prompted her to take to the road, is the way such inward anxiety translates into outward restlessness. In the story “Ship Island” (1964), for example—the destination of Smith’s pilgrimage—college-age Nancy Lewis rejects the middle-class society that her own family is desperately seeking to enter. Slipping away from a young man who is the perfect social match, she accepts the invitation of two dubious older men who agree to spirit her off on an adventure more suitable to her mood. Just before slipping away completely, dissolving into the sea as a mermaid, she says without apology to the perfect young man, “I guess it’s just the way I am. I just run off sometimes.”

In the decades following Smith’s dramatic escapade, Spencer burnished her reputation for daring and subtlety in the art of narrative. Whether setting her work in her native Mississippi or in such far-flung locales as Italy and Canada, following the trajectory of her eventful life, she continued to introduce us to women making rash decisions in some cases, strategic compromises in others, as inexpressible longings complicate their responses to perplexing moral circumstances. She “proved herself an indispensable witness to the difficulties of having a home and then leaving it, to the struggles of smart, sexually alive young women trying to find their way in the world,” observes Allan Gurganus.

Yet her men can be equally complicated. In a crucial way, in fact, her relationship to her male characters is more foundational. Unsurprisingly for a writer who came into her own in a place and time dominated by Faulkner, the plots of her first three novels—Fire in the Morning (1948), This Crooked Way (1952), and The Voice at the Back Door (1956)—hang upon the wills, the fortunes, and the tangled psyches of men.

The male character who most fascinated Spencer is Edward Glenn. From the time he first walked onto the scene of her only play, For Lease or Sale, he troubled her imagination, returning to her pages in search of something, perhaps also to escape from something, in every case leaving turbulence in his wake. This volume brings the play together with the three stories she subsequently published about him—narratives that Spencer described as “disjointed parts of a novel that will probably never get written.” Taken on their own terms, however, these selections, spanning twenty years of Spencer’s remarkable six-decade career, confirm her place among the nation’s most accomplished writers.

For Lease or Sale grew out of an opportunity that arose in the 1980s while Spencer and her husband were living in Montreal. Like many novelists, she once reflected, she had always wanted to see her characters come alive upon a stage. So when a planned English-language theater approached her about writing a drama, she embraced the challenge. By the time she had a draft in hand, however, the theater’s prospects had died. The play gained new life in 1987, soon after she and her husband moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. A staged reading of the play attracted the notice of David Hammond, artistic director at PlayMakers Repertory Company at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He and Spencer worked closely together to refine the play’s shape, and under Hammond’s direction, in January and February 1989, it was performed to warmly appreciative audiences.

The play’s title reflects its central dilemma: the forced necessity of a Mississippi family to sell the generational home place. Once a grand estate on the outskirts of a small town, by the time of the play’s mid-twentieth century setting it faces the threat of sprawling suburbia: the land has been rezoned to allow residential subdivision, and consequently its tax value has skyrocketed. The elder Mrs. Glenn, a widow raising a granddaughter in what might euphemistically be called reduced circumstances, beckons her son home to negotiate a resolution.

Many southern narratives, including some of Spencer’s, take as their point of departure the aristocratic white Protestant family in decline. In this case the family story came second, constructed to frame a particular situation. The first image to form in Spencer’s mind was that of an older man talking with a young girl. The man was Edward (the son), the girl his niece. The play’s working title was “Edward.”

A few facts about Edward Glenn are clear enough. A well-educated and articulate small-town lawyer, he is thirty-eight years old. He has been in Mexico, nursing wounds from a bitter divorce, when his mother calls him home. But much about Edward is encased in mystery. He womanizes. He sometimes speaks of himself in the third person, as if acknowledging that he is a problem to be solved. His answers to reasonable questions are rambling and contradictory; his emotions swing from scornful to self-pitying. He treats his eighteen-year-old niece Patsy with kindness, condescension, contempt, and at times a menacing suggestion of sexual control. His current love interest, Claire, is moved “to wonder if Edward really exists.”

Edward’s efforts to find a buyer appear genuine at first, however unsuitable Mrs. Glenn finds the prospects. But when he rejects even a generous offer that would leave his mother with a life estate in the property and the house intact, the truth emerges: he never intended to let the house go. This offer is being advanced by his ex-wife, Aline, whose unexpected appearance at the house sends him into a fury over past resentments. Edward and Aline had spent their marriage living here. And yet despite that history, beneath his anger, we see paradoxically that he cannot escape the mythological pull of the southern home. “Now that I’ve gone and laden it this way with other people’s blood and tears,” he vows, he has no intention of selling.

The play ends softly, with Edward and Claire alone in the house, dancing. One interpretation might be that they will stay together here and begin a new life. But their bodies are swaying to “Dancing in the Dark,” a song that once “belonged” to him and Aline—suggesting that such romantic closure is illusory.

Local critics reacted positively to For Lease or Sale. One reviewer called it a “subtle, adroitly written play” marked by “witty lines” and “delicious non sequiturs.” Another commented that the play “provides a uniquely endearing look at a family that is at once odd but also strangely familiar.” Though the same critics did register minor complaints that the play was too dominated by talk, that the concept might have lent itself better to the short story, Hammond identified a strength in Spencer’s playwriting that he saw paralleled in her prose fiction.

Elizabeth’s dialogue is what I call “loaded.” You know everything you need to know about her characters because their pasts are present in their words and actions. . . . We are all made from what we were, and what we were is thus present in what we are, but few writers can capture moments in which the full natures of our beings reveal themselves. I think Elizabeth does that, and I think she’s now found a way to do it on a stage.

In later years, feeling that Edward had more to say, Spencer did follow him into the short story, where she is on surer ground. With room to spread out on the page, she makes skillful use of point of view, manipulations of memory, atmospheric detail, and dialogue to draw us further into the project of reading Edward Glenn.

“The Runaways” (1994) finds Edward in Mexico. Here Spencer controls the point of view to convey his enigmatic personality. This brief story is told in third person, funneled exclusively through the mind of Joclyn, a single woman staying in the same low-rent cottage resort. She knows of Edward only what she observes or he chooses to reveal: she doesn’t even know his last name. Although readers familiar with the play can assume that this story fills in some background, without that context even the time of the story is unclear (for there is something rather timeless about a rustic setting high above a Mexican village, where iguanas lounge in the sun). This Edward, like the one who will return to Mississippi, thrives on emotional manipulation, and again we see that the root of his anger is the breakup with Aline. Joclyn seems to see through him, and yet she cannot dismiss him. The revelation that Joclyn is dying brings about a surprisingly tender conclusion.

With “The Master of Shongalo” (1996) comes the sense that Spencer is assembling threads of a more sustained narrative, for this story involves a second Mississippi home and family, and the central drama does not hinge upon Edward. Rather, he is a shadowy figure, unseen by anyone except Milly Weldon, a guest in this imposing home with the evocative name of Shongalo. A high school English teacher, Milly has come to spend a summer weekend at the request of an admiring student, Maida Stratton. A fully self-sufficient story about a girl with a crush on her teacher appears ripe for the telling, especially given her parents’ superior attitude toward this “spinster” whose class upbringing is decidedly beneath their own. (Practiced in the art of deflating pretensions, Spencer does not spare the Stratton family. When a boy at their country club parades his ignorance about Milly’s home town, which lies below the Delta in the state’s poorer region, Milly thinks: “What did they recognize except each other?”) But then Edward intrudes upon the scene.

Milly, struck by the opulence of this Colonial Revival-style house (complete with formal sunken garden), sets off on her first afternoon there to look for the library. She finds instead a strange man, “tall and rather messily dressed,” whose startled annoyance signals that he did not intend to be seen. In an exchange as charged with the power dynamics of sex as any in For Lease or Sale, he buys her silence with a kiss. She comes to believe that this man must be Edward, the Strattons’ mysterious cousin. His family once owned this home, among their other holdings. “He does unexpected things,” says Mrs. Stratton, grasping for words to explain him. “He wants unexpected things,” her husband adds. Milly had found him unexpectedly searching for things, pieces of paper, documents concerning the house, clues to his own past.

As disruptive and potentially derailing as Edward’s appearance is, the primary story of Milly and her student moves steadily forward until the two dramatic conflicts resolve, for Milly at least, in a moment of equilibrium.

We might call it a dynamic equilibrium, however, since “The Master of Shongalo” is told in Milly’s voice, and at a remove of forty years at that. With the shift from the focused third-person narration of “The Runaways” to the first person, we become even further distanced from Edward’s own psyche, and further removed from objective report, reliant now completely on Milly’s observations filtered through memory. The genius of Spencer’s narrative technique is on full display here. Not until the end do we learn that the story we’ve just heard unfolded decades earlier. This surprising revelation sends one back to the opening passages to discern precisely at what moment the story slipped so far into the past.

The slippage begins, as it turns out, at the beginning: with Shongalo, the name not just of a home, but of a lost Mississippi town, “long since absorbed into another one,” Milly tells us. (Situated in Spencer’s native Carroll County, the actual Shongalo was incorporated in 1850, only to be abandoned in 1859 when nearby Vaiden became a railroad stop. After the Civil War the town’s old buildings fell to arson, once a community of formerly enslaved people was found to be living in them. As to Shongalo the home, Spencer said it came to her in a dream.) The source of the name, likely Indian, is lost as well. “But the name,” Milly continues, “though I dream about it, is a real name. In the dream I know its reality without doubt, though when waking I doubt and am glad to have it proved. Once I see it proved, I can return to the dream. I can see it all.” Dreaming, she is certain of it; awake, she needs proof; the proof lets her dream again.

Inviting the reader to join her in the sunken garden, where she will relate her story, Milly proceeds to enact one of Spencer’s central propositions: that people rarely live entirely in the present. Her aim, as Hammond had observed in working on the play, is to show that “we are all made from what we were, and what we were is thus present in what we are.” Milly remembers her adventure at Shongalo, her secret encounter with Edward, with the clarity, the immediacy of last night’s dream.

Not for over a decade would Edward Glenn return to Spencer’s pages. This time, in “Return Trip” (2009), he can’t be missed. With his entrance, the past bursts in upon the present in full view of everyone involved, quietly roiling the foundation of a marriage.

The story is set in a mountain cottage on the New River north of Asheville, North Carolina, where Patricia and Boyd Stewart are vacationing. Patricia is a distant Mississippi cousin of Edward’s; though they had grown up together, they haven’t seen each other for years. Edward now lives in California, where he was recently widowed. On a day’s notice, he flies to Asheville, hoping to see the couple as his first stop on a cross-country trip to assuage his grief.

A wary unease sets in from the first register of Edward’s voice—the phone message announcing his plan to fly in for a visit, “if at all welcome.” His tentativeness suggests that he is “more than slightly aware that he might not be,” as Patricia reflects. The reassurances she offers Boyd that “he won’t be a bother” serve as thin veneer for a deep, unarticulated apprehension. When their son Mark rolls up on his motorcycle, paying an unannounced visit from college, the tension sharpens.

The unspoken is made plain in the image of Mark’s face. He looks like Edward.

Hiding beneath the surface is an incident that happened right after Patricia and Boyd’s wedding, in Mississippi. A wedding party at an aunt’s home stretched into a stormy night, electricity out, drink and family talk flowing freely. Patricia and Boyd had been assigned the bedroom that Edward, one of the guests, was accustomed to taking. Eventually Patricia found her way to bed and quickly passed out. An hour later, she awoke to Boyd standing in the middle of the room, railing at the sight of Edward lying next to her. “You’d have to see he hadn’t even undressed,” she retorted, maintaining her innocence from that point on.

During an awkward dinner that evening in North Carolina, Edward confides that the death of his California wife has unmoored him. He would move back to Mississippi, he says, “if it weren’t for Aline”—a knowing remark that sends him and Patricia down a tunnel of shared memories. Next day, he and Mark start to work on Mark’s motorcycle; needing parts, they drive down to Asheville. After a pleasant afternoon together, Edward abruptly announces he is taking off—and heads to the airport.

Alone that night, Patricia again tells herself that nothing did happen, “both drunk as coots. No, it wasn’t possible.” But she can’t be certain. What happened that long-ago night remains an open question. It may not be the most compelling question, though. The return of Edward has left her longing for reunion with her entire family, the old embrace of the close-knit world from which marriage to Boyd uprooted her.

She kicked off her shoes, sat on the boat pier and put her feet in the cool, silky water. It was then she heard the Mississippi voices for the first time. She knew each one for who it was, though they had died years ago or hadn’t been seen for ages. Sometimes they mentioned Edward and sometimes herself. They talked on and on about unimportant things and she knew them all, each one. She sat and listened, and let the water curl around her feet. She knew she would hear them always, from now on.

“All but adulterous” is what one reader called this concluding passage—with reason—and yet it bears much more weight than that.