The Past Shapes the Future

Excerpt from Time and Tide: The Vanishing Culture of the North Carolina Coast (Blair, 2023)

The year was 1524, and Captain Giovanni da Verrazzano and his crew of fifty were just off the coast of what would many years later be named Cape Hatteras[, North Carolina]. The ship was La Dauphine, a Spanish 100-ton caravel on a voyage to find a northerly route to China for Francis I, the king of France, and his syndicate of Florentine merchants and bankers of Lyon.

The presence of the small ship, captain, and crew from Europe brought with it the beginning of the end for the Hatterask Native Americans who had called the Outer Banks home for 1,000 years. It was also the beginning of a new and different civilization that was forced to adapt over the next five centuries to violent storms and a powerful ocean that often sank every kind of boat and ship to its floor. In this time, there were human conflicts, including revolutions, war, and slavery; there were advances, such as the first flight of man in a powered aircraft; and there were the endless battles of man against the sea, including the first life-saving station in the United States, commercial and sport fishing, boatbuilding, and lighthouses to guide sailors. And finally there came the endless buttressing of sand in an attempt to hold back a relentless ocean from reclaiming the land, homes, and lives of the people of the North Carolina coast.

The Coast’s First People

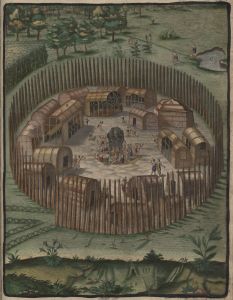

Today there is very little evidence left of Native Americans’ presence along the coast. There was a large shell burial mound on Harkers Island at one time, but the shells were used to build a new road. About all that remains are place names: Hatteras for the Hatterask tribe, Core Banks for the Coree tribe, Roanoke Island for the Roanoke tribe, and the Neuse River for the Neusiok tribe. During the Woodland period (roughly 1000 BC–AD 1600), these original North Carolinians were Iroquoian, including the Tuscarora, who occupied the coastal plain between Ocracoke Island and Topsail Island, inland all the way to the central Piedmont. The Neusiok and Coree, also of the Iroquoian group, occupied the Cape Lookout area of modern Carteret County and the waters of Craven County. Algonquian tribes settled and hunted the northeastern region of the state, including the Outer Banks north of Ocracoke and the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds, inland to the approximate western limit of the coastal plain. Representative tribes of the Algonquian group included the Chowanoke, Hatterask, Moratuc, Croatan, Secotan, Pamlico, Roanoke, and Weapemeoc (Yeopim). The Frisco Native American Museum and Natural History Center in Frisco is a good place to visit for more information on Native Americans on the Outer Banks. Unfortunately, there are no ideal sources for reconstructing the early coastal environment that the Native Americans lived in, but understanding their uses of the land and the later European perspectives can be instructive. Knowledge of Native American culture along the coast is limited to archaeological evidence and sparse accounts from colonizing expeditions from the 1580s to the 1590s. Algonquian tribes that early explorers encountered were unified only by similar language, not similar culture. They were hunter-gatherers to the extent that they used the barrier islands to fish, hunt, and forage. The first coastal residents lived on the shores of the Outer Banks and the coast southward to what today is South Carolina. Artifacts such as hooks made of bone provide evidence that they were fishermen and were agrarian, growing a variety of vegetables.

They made permanent settlements only along the denser stretches of maritime forests, such as behind Cape Hatteras (Cape Hatteras Woods), which provided protection from storm surges and gale force winds. The Croatans settled in these wooded and safe areas. The Croatans were likely the first Native Americans to befriend the first European settlers. Many but not all historians agree that they were known for their openness to early British settlers and explorers. It is believed that Manteo, one of their chiefs, was the first Native American to be baptized and actually travel to Europe. The Roanoke Island town of Manteo is named for him. Although the relationship between Native Americans and white Europeans was in general less than positive, the early explorers and settlers along the North Carolina coast would have had it much worse if the natives had been hostile instead of generally hospitable.

Pomeiooc Village, Theodor de Bry, 1590, originally published in Thomas Harriot’s 1588 book ‘A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia’. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Arrival of the Europeans

Rich and powerful European monarchs and wealthy merchants, who were keen on finding new resources for their subjects (and filling their own coffers), contracted with explorers to find riches in the New World—getting richer, more powerful and thus ensuring themselves a place in history. Some explorers were successful, others not so much. And some fell somewhere in between becoming famous in their time and vanishing into obscurity. An explorer important to the North Carolina coast was Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian sent west by King Francis I of France to search for a northwest passage to Asia. In 1524 Verrazzano found what he thought was the Orient: what was to become over 200 years later the coast of North Carolina (statehood was granted in 1789). His mistaking the Outer Banks for the Orient was considered factual until cartographers finally corrected his error a century later. Obviously, Verrazzano’s navigating skills left a lot to be desired, since the North Carolina coast is just about as far from China as you can get. Accidentally or not, Verrazzano was responsible for opening the Atlantic coast to the world while at the same time sealing the fate of the original inhabitants.

When Verrazzano left the Cape Fear River somewhere around Bald Head Island and sailed his caravel La Dauphine north to Hatteras Island, there may have been as many as 2,000 natives, Algonquians and other tribes, living along the coast. Believing that they were looking at the “Western Ocean” and China, Verrazzano and his crew of fifty thought the coastal Native Americans were “Orientals.” They reported on the characteristics of the coastal plains peoples by describing the natives they encountered on Bogue Banks and at the mouth of the Cape Fear River as “of a russet color,” tall, strong, and sporting long black hair worn “like a little tail” (da Verrazzano, 1524). The Native Americans were at first uneasy but soon became tolerant of if not exactly friendly toward the visitors.

Giovanni da Verrazzano, gravure de F. Allegrini. Scanne de Coureurs des mers, Poivre d’Arvor, via Wikimedia Commons.

Other voyagers to the North Carolina coast included Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, a Spaniard, and the Italian Amerigo Vespucci. Ayllón is credited with finding the Cape Fear River, what he called the “Rio Jordan,” in 1526, although this discovery has been debated by historians. The ill-fated voyage completed by Vespucci between May of 1499 and June of 1500, as navigator of an expedition of four ships sent from Spain under the command of Alonso de Ojeda, has been authenticated, unlike some other voyages. During this voyage to North America, he came upon the Cape Fear by accident and reported the terrible conditions, since the expedition was met by mosquitoes and unfriendly native people. Since Vespucci took part in it as navigator, he must have been experienced, but it does not seem plausible that just the year before, between 1497 and 1498, as some historians believe, he had made a voyage up the coast from Florida to Chesapeake Bay. It remains uncertain and unverified that this earlier voyage ever happened.

A half century after the first exploration of the North Carolina coast by Europeans, the coastal region attracted primarily English immigrants, including indentured servants transported to the colonies and descendants of English who migrated from Virginia. In addition, there were waves of Protestant European immigrants, including Irish, French Huguenots, and Swiss Germans who settled New Bern. A concentration of Welsh (usually included with others from Britain and Ireland) settled east of present-day Fayetteville in the eighteenth century. For a long time, the wealthier, educated planters of the coasts not only held sway over the region but also dominated local government. This was possible, in part, due to the influx of thousands of Black enslaved people from the West Indies and Africa. By the late 1700s there were over 40,000 enslaved people in the colony. Many ended up being “sold south” to the over 450 plantations with 1,000 acres or more in South Carolina.

The Lost Colony of Roanoke

During the growth of European immigration to the Atlantic Seaboard, an historic and ageless mystery of epic proportions occurred along the coast of what was to become North Carolina. The disappearance of over one hundred of some of the first English settlers in North America from their settlement on Roanoke Island is one of the most intriguing mysteries in world history; it’s also the name of a famous outdoor play by Paul Green, called The Lost Colony, set in Manteo, not too far from the actual location of the original colony on Roanoke Island. The play is famous in part because it was where Andy Griffith (Sheriff Andy Taylor of The Andy Griffith Show TV fame), buried on Roanoke Island in 2012, got his start as an actor. He acted in the outdoor drama from 1947 to 1954.

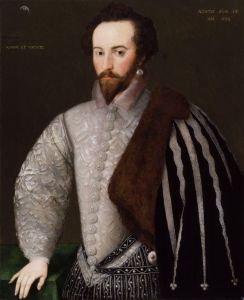

A brief version of the story known by most North Carolinians as the Lost Colony starts with some pretty brave folks setting sail from England for the “New World” that had been “discovered” by their fellow countrymen in 1524. An early supporter of colonizing North America, Sir Walter Raleigh, a landed gentleman, soldier, and explorer, sold his family business in Ireland, returned to England in 1581, and took part in court life, becoming a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I. In 1584, she granted Raleigh a royal charter authorizing him to explore and colonize America and any “. . . remote, heathen and barbarous lands, countries and territories, not actually possessed of any Christian Prince or inhabited by Christian People,” in return for 20 percent of all the gold and silver found there (Thorpe, 1909). This charter specified that Raleigh had seven years to establish a settlement, or else lose his right to do so.

Sir Walter Raleigh, circa 1590. Collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, via Wikimedia Commons.

One expedition of two ships directed by Raleigh and under the command of Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe left England on April 27, 1584. The ships landed on the coast of North Carolina on July 13, 1584, arriving first around the Cape Fear River and later on Hatteras Island, possibly around Oregon Inlet. This landing marked the first encounter of English people with native people on the Carolina coast and the first time the English flag waved in the New World. However—and this is open to speculation—this first encounter with native people may not have gone well. The English ran out of food upon arrival and would or could not get resupplied by the local inhabitants. So they sailed back to the queen to report that they had “discovered” the New World, and because she was known as the “Virgin Queen,” the new land should be called “Virginia.” Raleigh wasn’t too happy about this less-than-successful trip, and even though he stayed behind in England for a time, he didn’t give up. In 1585, Raleigh was knighted, appointed Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall, and made a vice admiral. He was also a member of Parliament. Although he himself never visited North America again, he invested in a number of additional expeditions across the Atlantic to North America between 1585 and 1588. These expeditions were funded primarily by Raleigh and his wealthy friends but never provided the steady stream of revenue necessary to maintain a colony in America. (Raleigh did lead expeditions in 1595 and 1617 to South America in search of the golden, mythical city of El Dorado.)

The second expedition Raleigh sent to Roanoke Island was in 1585. This group was led by Ralph Lane and included Thomas Harriot, a scientist, and John White, an explorer and artist sent to sketch New-World plants. After the Algonquians probably scared off the first colonists, White and his new group tried to befriend them. He figured that this was essential if their group was going to make it in the New World. The group gathered much information about the indigenous people. Reflecting the attitude of most Europeans of the era, Harriot described a people who were “very ingenious” and yet clearly inferior and in need of being brought “to civilities” (Harriot, 1590). The two groups got along for a while. The Englishmen even baptized an Algonquian named Manteo and crowned him Lord of Roanoke, which no doubt came with few privileges. However, supplies ran low again, and so, after just a short stay in 1587, White and a small group returned to England. He had planned on returning to the New World within a year, but that didn’t happen. Instead, the rest of the colonists were left on Roanoke Island for three years. Delayed because of war with the Spanish Armada and privateering forays south toward Cuba, John White finally landed on Roanoke Island again in August of 1590.

When White returned, and this is the mysterious part of the story, the 115 colonists—including his wife and daughter, his infant granddaughter (Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the Americas, in 1587), and the other hundred or so settlers—were nowhere to be found. The only signs of them were the letters CRO carved on a tree and the word CROATOAN carved on one of the colony’s wooden fence posts. When White had left the settlers, he had made an arrangement that if they had to move from the original site, their destination would be carved into a tree or corner post. White figured that they had moved to Croatoan Island (modern Hatteras Island), but a hurricane prevented him from looking for survivors.

Etching depicting John White’s discovery of the word CROATOAN carved at Roanoke’s Fort Palisade in 1590. Public domain.

Whatever the fate of the colonists, the settlement is now remembered as the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island, a mystery that’s lived on for centuries. Over the years, there have been conspiracy theorists and a few legitimate scientists who were convinced that the colonists tried to sail back to England and were attacked by Spaniards. Others have said that a disease killed them, but there were no bodies reported found and their houses had also disappeared. Some believed that they had drowned and been swept away during a bad storm in 1588. Still others have said that they ran out of food and starved. I think I see a theme here. But none of them had any valid proof, so the disappearance continued to be a mystery. One theory that has endured is that the settlers were absorbed into friendly Native American tribes, perhaps after moving farther inland seeking food and shelter. Since the late sixteenth century, explorers, archaeologists, and historians have investigated the mystery of the Lost Colony of Roanoke, all failing to find truly definitive answers.

Recently, two independent archaeological teams have found remains suggesting that at least some of the Roanoke colonists may have survived and split into two groups, each of which assimilated itself into a different Native American community. One team has excavated a site near Cape Creek on Hatteras Island, around 50 miles southeast of the original Roanoke Island settlement, while the other has focused on a site on the mainland about 50 miles northwest of the Roanoke site.

Cape Creek, located in a live oak forest near Pamlico Sound, is believed to be the site of a major Croatan Native American town center and trading hub. In 1998, archaeologists from East Carolina University stumbled upon a unique find from early British America there: a 10-carat gold signet ring engraved with a lion or horse, believed to date to the sixteenth century. The ring’s discovery at Cape Creek prompted further excavations at the site, which produced a small piece of slate that may have been used as a writing tablet and part of the hilt of an iron sword similar to those used in England in the late sixteenth century, along with other artifacts of European and Native American origin. The slate, a smaller version of a similar one found at Jamestown, bears a small letter m still barely visible in one corner and was found alongside a lead pencil. Unfortunately, in 2017 it was discovered that the signet ring was actually made of modern brass, not gold, so it could not have been associated with the Lost Colony.

In addition to these objects, the Cape Creek site yielded an iron bar and a large copper ingot, both found buried in layers of earth that appear to date to the late 1500s. At the time, Native Americans had no such metallurgical technology, so these objects are believed to be European in origin. Some of the artifacts were thought to be trade items, but others may well have belonged to the Roanoke colonists themselves, who could have assimilated with the Native Americans but kept some of their needed goods.

The discovery in 2012 of a watercolor map drawn by none other than John White inspired the search at another site, known as Site X, located on Albemarle Sound near Edenton, some 50 miles inland. Known as La Virginea Pars, the map now housed at the British Museum shows the East Coast of North America from Chesapeake Bay to Cape Lookout, including several “Indian” outposts and villages. White began drawing the map in 1585, two years before he became governor. Researchers using modern imaging techniques spotted a tiny four-pointed star, colored red and blue, concealed under a patch of paper that White had used to make corrections to his map. The star was thought to mark the location of a site some 50 miles inland that White alluded to in testimony given after his attempted return to the colony. If such a site did exist, it would have been a plausible destination for the Roanoke settlers. Based on these more recent findings, scientists think the Roanoke colonists may have moved inland to live with Native American allies sometime soon after White left.

However, it should also be taken into consideration that, at the time, relations with several other tribes were less than amicable. Roanoke was in the center of friction between the colonists and local Secotans and Chowanokes, who controlled access to nearby waterways. Though these discoveries don’t solve this historical mystery, they do point away from Roanoke Island itself, where researchers have failed to come up with definitive evidence of what really happened to members of the Lost Colony. Archaeological teams are hopeful that new finds will yield more clues. Despite the lingering mystery, it seems there’s one thing to be thankful for: the lessons learned at Roanoke may have helped the next group of English settlers, who would establish their own colony at Jamestown about 100 miles north some 17 years later, on May 14, 1607.

The disappearance of the members of the sixteenth-century Roanoke colony has mystified local residents, tourists, history enthusiasts, archaeologists, and even park personnel for decades. The original 1937 Lost Colony play by Paul Green that is enacted on the waterside site of the original colony has been changed many times over its 85-year run, yet its plot and narrative continue to attract thousands of visitors every year and provide theatergoers a suspenseful and historically valuable experience. A new score and a reworked script now more accurately present Native American traditions and characters. Using white actors in bronze makeup was common for many years in theater. Today, the Tony Award–winning play includes several cast members from the Lumbee tribe and other Southeastern tribes, and the score incorporates more Native American–oriented themes.

Privateers, Pirates, or “Pyrates”?

Algonquians and other native tribes along the North Carolina coast experienced much loss and pain with the arrival of the colonists, but they also witnessed the making of history. They were still around when Edward Teach (or Thatch, as some historians call him) captained a ship, Queen Anne’s Revenge, that was sunk in waters around Beaufort Inlet about a mile from Fort Macon State Park, on Bogue Banks next to Atlantic Beach. Whether or not the Algonquians and other tribes made contact with pirates like Teach, better known as Blackbeard, or even paid them much attention is not known. What is known is that the piracy of the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century, called the Golden Age of Piracy, lasted for only a little over a year on the North Carolina coast: off and on from 1713 to 1715. It’s hard to believe that piracy was actually so short-lived when it remains so celebrated today. In most bookstores, gas stations, and food marts just about anywhere along the coast today, shelves are filled with books about Blackbeard, Captain Kidd, and other famous pirates who hung out on the Outer Banks and a few points south. The truth is that pirates known to have visited the North Carolina coast spent most of their time roaming the waters farther south, along the shores of South Carolina, Florida, and especially the Bahamas.

In the summer around Ocracoke Island, up and down the Outer Banks, and even around Morehead City, it’s common to see kids in three-pointed pirate hats and eye patches growling “AARRHH . . . matey!”—a pirate’s saying kids never seem to tire of. Flags with the skull and crossbones, silhouettes of Edward Teach with his beard on fire, and T-shirts emblazoned with sayings like “Pirates only want me for my booty” and “I’m a Pirate. Just add rum” collectively add to the popularity and moneymaking prospects of mock piracy, but are not based on sound history. There is nothing wrong with this kind of commercialism. It’s just that it tends to support misconceptions about who pirates were, what they were really like, and what they actually did. They were nothing like Johnny Depp’s portrayal of Jack Sparrow, the Pirates of the Caribbean film series pirate who was inspired by Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards, not the real Blackbeard. And as far as what a real pirate was like, few T-shirts show the face of Peter Pan’s Captain Hook staring in terror at a bloody hook (for the uninformed, in the story by J. M. Barrie, Hook was afraid of his own blood). It turns out that not only are familiar pirate stories misleading, but a few are outright fabrications.

Ocracoke Pirate Jamboree, 2015. Photo by Natasha Jackson

Pirates (or “pyrates,” the Old English spelling) were by and large ruthless, greedy, cheating, nasty, carousing, merciless, and doubtless not all that amusing. Simply put, many were bad dudes (and a few dudettes). Luckily, the “Golden Age of Piracy” along the North Carolina coast lasted only a few months, not for an entire age. And truth is, with the exception of a few gold flakes found on the ocean floor off Ocracoke Inlet, it wasn’t very golden either.

Although we think of pirates as being lone figures roaming the seas, loyal to none but themselves, many were actually privateers—captains of ships authorized by their governments (primarily England and Spain) to attack and raid enemy ships. Privateers operated independently, apart from the royal navies, but were an accepted part of naval warfare from the 1500s to the 1800s. Private investors paid for privateering in hopes of profiting from stolen goods, while governments appreciated the damage they did to enemy commerce. They were simply mercenaries.

During the many wars fought between England and Spain from the 1580s to the 1760s, Spanish privateers frequently raided the coast of North Carolina. In 1747, Spanish privateers anchored around Cape Lookout sent men ashore to capture the town of Beaufort. They immediately ran into the very unfriendly local militia, which forced the overpowered and shocked invaders back to their ships.

Legitimate privateers (if there really was such a thing) and experienced sailors employed during the Spanish War of Succession turned to piracy when they found themselves out of work after the signing of the conflict-ending Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. They didn’t stay unemployed for long. Because of the acceptability of privateering, it happened to be a great time to be a pirate. Shipping lanes were filled with rich cargo bound for European cities, and with the exception of the English and Spanish navies, there were fewer and fewer European ships monitoring the waters where pirates roamed. Colonial forces were generally too weak to fight off well-armed pirate ships operated by shady yet seaworthy captains and crews dead set on getting rich.

Most of the infamous pirates of the day took advantage of excellent hideouts created by inlets and harbors along North Carolina’s coast. For example, Stede Bonnet, known as the “Gentleman Pirate” because he was from a prominent family in Barbados, sailed with Blackbeard. He battled in the Cape Fear River with a ship sent by South Carolina’s governor and was hanged in 1718 for piracy in Charleston. And there was Charles Vane, an especially nasty pirate, who tortured and killed captured sailors and cheated his own crews. His stint in North Carolina included partying on Ocracoke Island. He befriended fellow pirate Calico Jack Rackham before being hanged. Calico Jack was famous for introducing the Jolly Roger skull and-crossbones flag, and for sailing with two female pirates, Anne Bonny and Mary Read. Like his colleagues, he was executed in Port Royal, South Carolina, in 1720 by hanging.

Captain William Kidd, another renowned privateer and pirate, was immortalized by stories of buried treasure, including treasure reportedly hidden on Money Island off Wrightsville Beach (next to Wilmington). However, his actual presence along the coast is disputed. He too was tried and hanged for piracy in 1701. And the truth is that Kidd was probably more a privateer than a pirate.

Since the late eighteenth century, pirate treasure hunters have dug, trenched, dynamited, bailed, and pumped thousands of gallons of water and mud with little success. As recently as the 1950s, treasure hunters searched around Elizabeth City and Edenton for Blackbeard’s and others’ booty. Surprisingly, thousands of dollars’ worth of old coins and artifacts were actually found around Bath at Plum Point. But as with most treasure claims, the booty was never very much, and it was never officially tied to Blackbeard or any other known pirate, for that matter.

Unlike gold and gold coins, some pirate treasures are so historically important that assigning monetary value to them is impossible. Hundreds of historical objects have been found, including a diminutive signal gun; turtle bones (possible remnants of a favorite pirate food); a funnel-shaped spout that served as a urinal; and an intact piece of window glass, blue-green and rippling like a sculpture from the sea. A dive in 2010 yielded an ornate sword hilt made of iron, copper, and an animal horn or antler. Even though riches have been sparse, a few determined folks still dig for pirate treasure.

Blackbeard: Half Man, Half Legend

Legend has it that Blackbeard, whose real name is thought to have been Edward Drummond, later changed to Edward Thatch, Tatch, Teach, or Teache, was a giant of a man. Some accounts put him at just under 7 feet tall and barrel chested. He was named for his impressive facial hair, which fell to his waist and was styled in braids—allegedly on occasion soaked with grease and caught on fire to scare his enemies. He seized his best and biggest warship, La Concorde, from French slave traders in 1717 and renamed his prize in honor of the English monarch, calling the big ship Queen Anne’s Revenge. He spent the next several months privateering/pirateering in the Caribbean and along the coast of South Carolina, amassing a veritable navy of smaller boats and a huge crew of fellow pirates.

Edward Teach, commonly known as Blackbeard, 1736. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Queen Anne’s Revenge, a French-made frigate, along with one or two other boats loaded with Blackbeard’s pirates, blockaded the Port of Charleston, holding prominent citizens hostage in return for a cache of much-needed medicines and some gold. In June of 1718, Blackbeard then retreated to the hidden coves and inlets of the North Carolina coast, where Queen Anne’s Revenge foundered on a sandbar, it is believed, and slowly sank just off Beaufort Inlet. According to a deposition given by David Herriot, the former captain of Adventure, “the said Thatch’s ship Queen Anne’s Revenge run a-ground off of the Bar of Topsail Inlet.” Herriot further stated that his own ship “run aground likewise about Gun-shot from the said Thatch” (Queen Anne’s Revenge Project, n.d.).

Details of how the ship ran aground remain a mystery. Some believe that Blackbeard’s ship was just another victim of the treacherous waters and sandbars that tend to shift during storms, confounding even modern captains. Others, however, think Blackbeard deliberately abandoned his ship, which was too big to navigate North Carolina’s shallow inlets and sounds, in order to minimize his crew, transferring whatever treasure he had amassed to a couple of the smaller ships known to be in his fleet at the time. He then rested his crews, probably did some drinking, and made repairs to his ships on the Outer Banks and the Crystal Coast.

Blackbeard lived only a few months after he abandoned Queen Anne’s Revenge. He used his newly possessed ship, the Adventure, to capture French, Spanish, and even British ships’ spoils, amassing quite a treasure. During this time, he halfheartedly tried to give up the pirate’s life by settling down, marrying a 16-year-old girl, and buying a big house in Bath, North Carolina (he already owned a large house on Ocracoke Island). His stint as a landlubber lasted only a few short months, however, as he apparently stayed drunk, mistreated his young bride, and yearned for the sea and life aboard ship. He was also planning to turn Ocracoke into a haven and refuge for his fellow pirates. But his plan was foiled when Governor Eden in Bath sent a delegation to Governor Spotswood of Virginia imploring him to capture and finally do away with Blackbeard. Spotswood agreed and sent two British warships after him. On November 22, 1718, Blackbeard was ambushed on the Adventure by a Royal Navy lieutenant from Virginia, who sailed home with Blackbeard’s head dangling from his bowsprit, the long pole that extends from the ship’s bow.

The pirate’s legend, though, swashbuckles on. The story lives on that during a full moon Blackbeard’s headless body still swims around Teach’s Hole, the place near Ocracoke Inlet identified on maritime maps as where he was killed. His popular exhibit at the North Carolina Maritime Museum has been supplemented with dozens of never-before-seen artifacts that excavations of the wreck of Queen Anne’s Revenge continue to reveal. Since 1996, when Queen Anne’s Revenge was discovered and became the property of the people of North Carolina, archaeologists have found hundreds of historical objects, including a small signal gun and a pewter syringe allegedly used by Blackbeard to treat his syphilis. Not long ago, archaeologists recovered several large cannons from the wreck. The site is 25 feet underwater, and less than a mile and a half from shore. Over the centuries since Queen Anne’s Revenge met its demise in 1718, hundreds of commercial and sport fishermen and pleasure boaters, including the author, have unknowingly cruised and even fished around the waters within only a few hundred feet of the wreck.

However limited along the coast of North Carolina, the Golden Age of Piracy still had an impact on the character and distinctiveness of the culture of the coast. With their adventurousness and often rowdy natures, pirates and privateers alike caroused with and even lived among local citizens. And still today, some 300 years later, there is evidence of the impulsive and sometimes wild temperament of piracy. Few events, especially those that were so short-lived, have had the longevity of influence as has piracy. From Beaufort’s Pirate Invasion, based on the Spanish invasion of Beaufort in the 1700s, held each year in August, to tours of Blackbeard’s home, the Hammock House (also in Beaufort), to tourist outlets selling eye patches and plastic swords, piracy continues to have an effect on visitors and locals along the coast of North Carolina.