Think of a Wonderful Thought: On Cuba, Nostalgia, and What Might Be Next

They called it Operation Pedro Pan, in a nod to J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. But the children who took part in Operation Pedro Pan were not Londoners, and they had no pixie dust to help them fly, nor very many happy thoughts to go along with the dust for that matter. From December 1960 to October 1962, more than fourteen thousand unaccompanied Cuban children came to the United States. Their parents, fearing Marxist indoctrination of their children on the island, packed up their kids and sent them off, alone, to Miami. The Catholic Welfare Bureau took over from there, placing the children in foster homes, with the firm belief that Fidel Castro would be gone very soon, and the children could return home.

But unlike Wendy, John, and Michael Darling, the Cuban children never came home. They were Lost Boys and Lost Girls in the Neverland that is the United States.

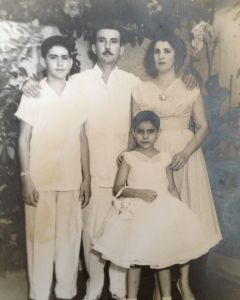

My mother-in-law, a feisty and loving woman, was a Pedro Pan child. Because she had family in Union City, New Jersey, she skipped the foster parent part of the experience. Her own parents joined her years later, leaving Cuba via Madrid. I think of her often as a little girl in a strange world, an unknown language in her ear, through that first winter which must have seemed so terrifying and so beautiful. And to think that there were so many Pedro Pan children! Until last summer, Operation Pedro Pan represented the single biggest exodus of unaccompanied minors. Their number was dwarfed by more than twenty thousand with the flood of children who came alone to the United States in 2014, fleeing Central America. The Pedro Pan kids are some of the most successful Cuban-Americans. They include senators and musicians, CEOs and doctors. One wonders what the story of the Central American child refugees will be.

All of this brings me to one very famous Pedro Pan child—the salsa singer Willy Chirino. Born in Consolación del Sur in Cuba, Chirino earned his Lost Boy badge at the age of fourteen. In the United States, he’s become a household name in many Hispanic homes, but especially among Cubans and Cuban-Americans. His hit “Nuestro Dia (Ya Viene Llegando),” or “Our Day (It’s Coming),” is an anthem for Cubans in this country. I’d wager money that most Cubans have likely shed a tear at least once while listening to the song. I know I have.

The lyrics tell of Chirino’s Pedro Pan experience. “Just a boy,” he sings, “my father dressed me in a sailor suit. I had to sail ninety miles to begin my life as a foreigner.” Later, Chirino tells us what’s in his suitcase, including coloring books and a book about José Martí, the famous poet-patriot of the nineteenth-century Cuban War of Independence (I cannot bear to call it the Spanish-American War, which lasted only four months compared to nearly two decades of the Cuban struggle against Spain. Secretary of State John Hay called it a “splendid little war.”). In Chirino’s suitcase is also “a dream and a danzón,” a traditional Cuban dance.

As the song progresses, the contents of the suitcase go from the specific to the hazy and abstract or the downright impossible. In his luggage he also brings a palm grove, and a bohío, a kind of thatch-roof house found in the Cuban countryside. Chirino even sings about relocating an entire city—Pinár del Rio—from Cuba to Miami. That’s quite a roomy suitcase.

It is an intensely nostalgic song, and one that replicates Miami’s fifty-year transformation into a kind of Alt-Cuba, or Cuba North, as I like to say. Private schools on the island, shut down by Fidel Castro in 1961 (coincidentally, the same year Ernest Hemingway left the island he called home for many years and killed himself back in his hometown, Oak Park) were reborn in Miami, down to the school songs in Spanish and the school shields. I attended one of these resurrected institutions, Champagnat Catholic School in Hialeah, Florida, stuck between a Sedano’s Supermarket and El Rincón de San Lázaro, a shrine to a character from a parable where people leave their crutches in thanks. Restaurants in Miami are called things like Old Havana and El Malecón, after the famous seawall in Havana. And an annual conference, Cuba Nostalgia, draws thousands of visitors. At the conference, one can traverse a huge map of Cuba that’s laid on the ground, and each year during the conference, my Facebook feed gets clogged with friends and family and friends of friends standing on the city they came from, or their parents came from, or even the cities their grandparents and great-grandparents called home.

That’s how far back it goes. Nostalgia in the Cuban diaspora is palpable. You can stick your tongue out and taste it. It’s in a cuisine that can no longer be found on the island thanks to rations, in the way Cubans cook in their homes (“This is how it used to be seasoned in Cuba”), in statements overheard while at the beach (“The beaches are more beautiful in Cuba. Let me tell you about Varadero . . .”), and even at our parties, where DJs still play oldies like Beny Moré’s “Castellano que bueno baila usted,” which was recorded in the 1950s.

Chirino’s “Nuestro Día” brings me to tears. Real, sloppy, choking ones. What triggers that? It must be the same soft spot that makes me get weepy during the hymns at church. It’s something about family, and loss, and feeling loved in spite of everything. Something like that. But as a writer, I’m torn. On the page, I want to tell the truth about a place, and I know that even in Neverland, things weren’t perfect. Even in Neverland, a dastardly captain can package a bomb as a gift, and a gaggle of boys miss their mother, even though they’ve forgotten what a mother even is. I want to know yesterday’s Cuba in all its glory and all its horrors. And there are plenty of both, to be sure.

As I write this, U.S. representatives are in Cuba, engaged in talks to bring about a normalization of relationships between my two embittered countries. There are those who see this as a total failure on the part of the United States. They are hoping for a complete turn-around on the island, á la East Germany. Others seem to think that this will lay down the pavement for a Cuba that will come closer to the Chinese model, except the economy will be tourist-based and not plastic tchotchke-based. I hope for the former, but I’d put money down on the latter.

What will be the effect on the diaspora? And on nostalgia? That remains to be seen. In a sense, the Cuban grip on nostalgia has been made even firmer by the isolation of today’s Cuba from the United States. Diasporic Cubans are a bit like that guy in high school, the one who peaked in eleventh grade. He’s still wearing 1990s-era flannel and listening to Pearl Jam, know what I mean? While we’re still thinking about how Cuba used to be, Cubans on the island have their own kind of traditions. A new nostalgia is being fomented today among a new generation.

A minor example: there’s a comedy duo, the Pichy Boys, who put out videos on YouTube about Cuba and Cubans. They’re living in Miami, but from what I can tell, are fairly recent arrivals in the country. They are funny as hell, but half the time, I have to Google the Cuban slang they’re using. It’s different from what I heard growing up. I have a book of idiomatic expressions here in my house called Así Hablaba Cuba, or “This Is How Cuba Talked.” Note the past tense.

A major example: Back in the 1980s and ’90s, a popular bumper sticker adorned many a Cuban American car. It was bright yellow, with a silhouetted Cuba, and the words “Yo no voy,” or “I won’t go.” In other words, the bumper sticker declared the owner’s insistence that to visit Cuba would be to put U.S. dollars in the hands of a dictatorship, cementing many a Cuban-American’s refusal to return to a Cuba that was not free. I haven’t seen one of those bumper stickers in years. Many recent arrivals, taking advantage of the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 that basically says that Cubans fleeing the island can stay in the United States, return to Cuba as soon as possible for a visit. What is exile, then, many people ask, if you can go back anytime you want? But many “new” Cuban exiles don’t seem to see it that way. Many of them wouldn’t put a “Yo no voy” bumper sticker on their car. The times (and the exiles), they are a-changing.

At the end of Chirino’s anthem, he begins to call out the names of former communist countries. “¡Checoslovaquia!” followed by the shouts, “¡Libre!” “Nicaragua, Polonia, Rumania, Alemania Oriental,” all sung enthusiastically, the “¡libres!” that follow getting louder. Then he shouts, “¡Cuuuuba!” which is, for Chirino, the hopeful apotheosis of the list. In the background, the Cuban national anthem kicks up, softly at first then gaining strength, and at last, the chorus comes back, “Ya viene llegando.” Our day is coming. That’s when I cry hardest. I don’t think it’s nostalgia that’s making me sad. It’s the force of history, and how that history feels so insurmountable. It’s the knowledge that Chirino released this song in 1991, and yet, here we are. Still in the same boat (pardon the pun).

Perhaps, nostalgia is a good thing. When it comes to Cuba, Cubans and Cuban Americans have really complex feelings about the island, the politics, the history of the place. The talking heads on the cable news networks show no such complexity, regardless of whether they think the embargo is an excellent idea or wish that McDonald’s would hurry up and put roots in Havana (McLechón Asado, anyone?). But in Cuban homes, and in our hearts, there is no clear-cut answer. Nostalgia, however? That’s pretty clear. It’s a hopeful looking back. It’s a sentiment that suggests a foundation of peace and prosperity in the timeline of the island. Bear with me if I indulge on occasion, or get misty during a pop song. It’s fortifying, in a sense, for when I return to the page, the work in progress, and must turn a clear eye on the story.

Besides, the occasional dose of pixie dust never really hurt anyone anyway.

very timely and interesting

Wow – I would love to see this place and hear the music in person. Gorgeous photos.