Antietam, Maryland. A lone grave. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-DIG-cwpb-01110 DLC]

Share This

Print This

Email This

Untrod Ground: Civil War History Today

Is there any better-trod topic in American history than the Civil War? In 2002 the Library of Congress estimated that 50,000 to 70,000 books and monographs about the conflict had appeared since its conclusion. In 2013, and nearly two years into the war’s sesquicentennial, that number is undoubtedly much higher. And then there are the dozens of Civil War journals and magazines, the hundreds of conferences, the thousands of lectures. It’s enough to make a book browser look upon the latest Ulysses S. Grant biography at Barnes & Noble and despair.

Yet the books keep coming, and somehow, they keep having something new to say. It is the nature of history, and history writing, and especially history writing about this seminal American story: if the war was what Robert Penn Warren called an “American oracle,” then its insights will by necessity change as America itself changes. The questions that a multiracial, globalized nation asks of its history in 2013 are very different from those asked by the same country fifty years prior, when it was a segregated superpower locked in a nuclear-tipped cold war.

During the 1950s, a time of often repressive national consensus, the questions revolved around proving that the war could have been avoided, the better to demonstrate that all was fine with America and always had been, save for the odd hiccup. A generation later, the country was reversed, and so were the questions: the war was inevitable, because conflict, not consensus, was endemic to the American political psyche—a view that came naturally to the ’60s generation. Traveling alongside were historians asking wholly new questions about slaves and gender and culture, things that their elders ignored but that the new, post–civil rights America made necessary to explore.

In asking different questions, historians not only get different answers; they come up with new evidence that feeds back on, and obliterates, received truths. Few historians in the 1950s cared to ask what women thought and did during the war; over the subsequent half century, new questions have led historians to examine previously overlooked sources, which in turn have shed new light on conventional wisdom about all facets of the war. Women, we now know, not only played important roles on the battlefront, but through their positions as informal political advisers and activists, they helped shape the course of the war on the homefront as well.

What sort of questions are historians asking today? If a consensus exists, it is that there is no consensus—if it’s not quite “anything goes,” it’s certainly a much more permissive, wide-ranging field of inquiry than before. The interest in culture, in women, and in the black experience remains, but they are less the ideological firestorms they were in the 1980s and ’90s. The radical, insurgent perspective has become the establishment.

At the same time, we do not yet see (at least in academia) a return to any sort of “great man” history; the war as seen by the average soldier remains more interesting to the latest generation of historians. Material culture and mass media are frequent subjects. In the New York Times’s Disunion series, we have published young scholars writing on Civil War music, Civil War humor, and Civil War literature, all of which points to further investigation in the coming years. Regional experiences are also of new interest—the war in the Appalachians, or the northern Ohio Valley, for example. That old chestnut about the Civil War pitting “brother against brother” is once again at the front of scholarly minds, as historians examine how communities along the north–south border navigated the violence of divided loyalties.

There is also a movement to put the Civil War in an international context. In part this involves a deeper investigation into the war’s diplomatic aspects, the view from London and Paris, as it were, embodied most recently in Amanda Foreman’s A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War. This is hardly new ground: Frank L. Owsley wrote King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America, still often considered the standard text on Civil War foreign policy, in 1931. But the staying power of that book, written by an avowed, if erudite, racist, demonstrates why a book like Foreman’s—and, hopefully, others to follow—is so needed.

Most significantly, scholars have clarified how deeply the Haitian revolution resonated through antebellum Southern society. The fear that a slave population could rise up and defeat a white master class—a fear underscored by the occasional domestic slave revolt—made Southern whites increasingly paranoid through the first half of the nineteenth century, to the point that any possible challenge to their social structure became a life-or-death threat. At the same time, they pushed endlessly for any avenue for expansion of slave-owning territory: the annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the invasion of Nicaragua by filibusteros. Indeed, it is impossible to understand the Southern fear of Republican power—culminating in Lincoln’s election—without understanding this international context.

This is hardly unique to Civil War history. Americans, including American historians, have long tended to see the country’s history in isolation, with any relationship to the outside world being relegated to subdisciplines like diplomatic history. But that has started to change. In recent decades scholars have insisted that the United States, from its earliest colonial moments, was a part of a transatlantic world, both influencing and influenced by events in Europe.

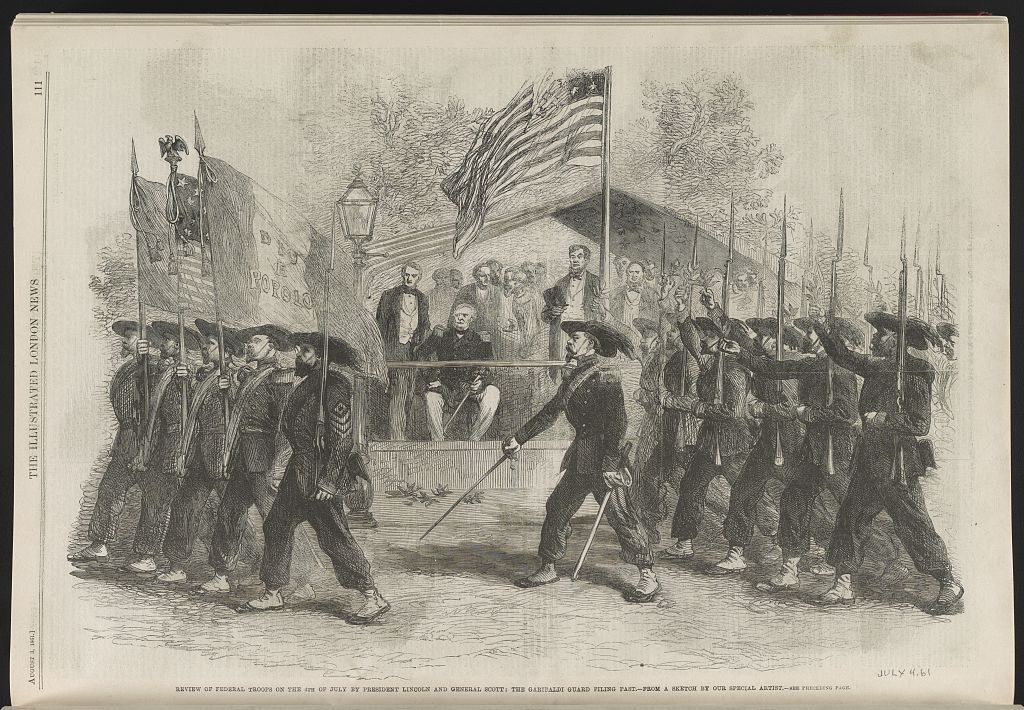

Review of Federal troops on the 4th of July by President Lincoln and General Scott; the Garibaldi Guard filing past. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-DIG-ppmsca-31563]

Thanks to improvements in information technology, historians can now ask questions that they never thought possible to answer. Scholars at the University of Richmond have shoveled thousands of Civil War–era pages from The Richmond Dispatch into a database, which they can sift through to find once-hidden patterns. For instance, they found that notices for runaway slaves tended to spike after Union victories, hinting strongly that slaves were not only well aware of the course of the war but willing to act on the news they received—conclusions that undercut conventional assumptions about slaves as passive, uninformed pawns in a white man’s war.

Yet, amazingly, there are wide swaths of Civil War history that remain poorly covered. Southern history, despite a few recent, groundbreaking works like Stephanie McCurry’s Confederate Reckoning, is woefully underappreciated. Perhaps this is one of the last vestiges of political correctness: taking the Confederate States of America seriously as an institution and the South seriously as a political culture is still thought by some to give them credibility, at a time when public displays of Southern pride and the Confederate battle flag still rub people the wrong way.

There is also much work to be done on the American West during the war. We tend to see the Civil War and the later settlement of the West as two discrete stories. But of course they weren’t: conflicts with Native Americans were frequent during the Civil War, most notably the Dakota War of 1862. Moreover, the war forced many Native American tribes to take sides, choices that reverberated through the rest of the century. At the same time, attitudes toward violence and power that were forged during the war helped ease qualms about massacring Native Americans later, a point brought home in recent books like Heather Cox Richardson’s West from Appomattox and Jackson Lears’s Rebirth of a Nation.

When we began publishing Disunion in November 2010, we weren’t sure how popular the series would be, or how much new there would be to say, at least to a general audience. Not only has the series been immensely popular, but we’ve also been impressed by the depth and breadth of new perspectives coming from young and old scholars, both inside and outside the university gates. While we like to think we’re publishing the best of what’s available, we also hope that the series inspires even younger scholars and writers to enter Civil War history. The field remains wide open, and ripe.