Holy Waters: A Ganges Baptism

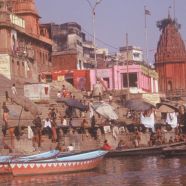

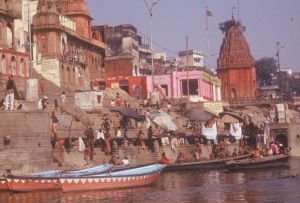

First I saw the iconic photos of the Indian holy river city—the wildly exotic skyline of the old maharajahs’ palaces along the Ganges, the smoking funeral pyres, the sunrise bathers at water’s edge. For me, the dusk and dawn pictures of Varanasi, with the turrets, fires, and smoke rising above the curved riverbank made the place seem almost a mirage, a watery oasis no traveler could ever reach. But for more than 2,500 years, Hindus have come here on pilgrimage. Varanasi is the home of Shiva: creator, destroyer, and sustainer of life. This city is the most auspicious place for a Hindu to die, the place to be released from the cycle of rebirth.

From the time I first saw the images, read the words “holy city,” I locked on with snapping turtle tenacity to the goal of getting there. I had no logical reason—there are other sacred sites and holy cities in India and elsewhere—I simply felt pulled.

My first attempt failed. In India to attend a convention of the Society of American Travel Writers, I tried to get to Varanasi but was stopped by severe monsoon flooding. I returned home to North Carolina with only the shimmering images of the place in my mind, a city sitting at the edge of “the other side,” at the edge of human life, otherworldly, the most exotic and wild frontier.

Twelve years later, I approached again, this time with a hard-won fellowship to do research for a novel set in this river city, the novel that was to become Sister India. When I left, I knew almost nothing of the story I would write, but I had argued that I should be funded to come because of my interest in comparing the religiosity of this place with that of the American South and its tradition of river baptisms. The funding won, I made my way to Varanasi. From the window of the plane, I could see land implausibly flat to the horizon, so huge it was as if I was looking at time zones, light years, or the curve of the earth, something that should only exist in the abstract, not rolled out beneath me. Immediately below, fields were green and cultivated, broken here and there by clusters of mud-colored, tile-roofed houses. Nowhere did I see the city. I didn’t fully trust that I was going to get to the Ganges.

The road from the airport was narrow through dense woods. The ride seemed far too long. When night fell, I started to worry and demanded to know where the cab driver—and the other man in the front—were taking me. The cab driver attempted to reassure me and kept driving. And driving. It was 1991—pre–smart phone, pre-texting. Sitting silent in the dark of the back seat, I was stiff with fear and anger.

Finally, a few lights appeared along the sides of the road. We came into traffic; the taxi’s lights flashed across a rickshaw, a bullock pulling a cart, people walking. A little farther along, a roadside vendor’s stall shone yellow for seconds as we passed. The air from the open windows was full of dust. There were no cars, only bicycle rickshaws. The roadside was dotted with tiny fires. This looked nothing like the edge of a city. We seemed to be driving into some kind of encampment.

The cab stopped. No river, but a sea of stalled rickshaws blocked the way. In Hindi, the driver questioned a passerby, then said to me, “Madame, we cannot go to your hotel.”

“What do you mean,” I kept my voice carefully level, “that you cannot go to my hotel?”

“There is a mela,” he said, “a religious festival, stopping all traffic on those streets. Not possible to get there.” A religious festival is one of the likelier targets for religious violence: the one situation that for my safety I must avoid. On the night of my arrival in New Delhi a week before, a terrorist bombing of a religious celebration in a nearby town killed forty-one people. I looked away from the driver to take a breath and think. A white cow stood with her face at my open window, her head filling most of the frame. In my current state, I was not even startled. She watches me, this cow, but with minimal interest. She is nursing a calf, her eyes contemplative.

“What am I supposed to do?” I said to the driver.

“We can all sit here and wait,” he said, “two hours, maybe three.” He offered an alternative, to find me a bicycle rickshaw, which would be able to travel through narrow lanes where a car could not and perhaps get me there sooner.

“The rickshaw, please.” He got out, left me with the cow and his silent buddy in the front seat. We waited, sitting, I’m convinced now, at the edge of the city. This was Varanasi, though what I saw seemed rural, like a village: the cow, the dusty road without cars, shadowy figures milling in the yellow light of a couple of stalls. My driver told me were here and I began to trust him.

He returned, bringing a young man with a rickshaw. I and my baggage for my three-month stay are transferred onto the seat behind the bike. I am at least out of the dark woods, presumably at the “gates” of the holy city. Almost instantly, we’re going fast in a new direction into dense and fast-moving traffic and I’m gripping the side of the bench with all of my three months’ worth of stuff.

None of the rickshaws had lights. The narrow lanes had no lights. Each overloaded vehicle was a shadow in the dark. A high-pitched bell rang and a shape careened toward us, wheels passing as close as an inch, then away.

We came to a stop: rickshaw traffic jam in a welcome patch of light. Loosening my grip on my bags, I leaned back. The air was nice, the heat of the day softened, and there was a tropical-night feel on this dirt street, walls rising straight up from the edge of the roadway. I was in Varanasi; I had no doubts now. Here’s Bimal’s Tailoring for Gents. A storefront orthopaedic surgeon’s office. A hammer and sickle painted on a wall. In a narrow open space, a few men sat on blocks and boards around a tea kettle on the coals of a little fire.

The rickshaws moved forward a few yards, then stopped again. I heard the steady beat of men’s voices, chanting in unison, from a little distance.

Another half hour, and, all at once, the traffic jam broke. In only minutes I was standing beside my bags at the front door of the Hotel Diamond, so grateful to be there that I paid the driver significantly more than he’d asked, pushing bills into his hand. “Dhanywad,” I kept saying. Thank you. “Bahut bahut dhanywad.” Thank you very very much.

I dragged my bags into the hotel lobby, blessedly ordinary, with a front desk and rows of numbered boxes for room keys. I hadn’t seen a river yet, but I had at last put my bags down in the holy city.

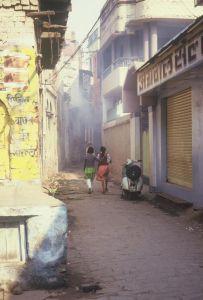

My first morning in Varanasi was the hottest since I’d been in India. It was like breathing dishwater. As I edged along the outer walls of the buildings, pressed there by the furious flow of traffic through narrow streets tight-packed with bike rickshaws and motorbikes, the three-wheeled auto-rickshaws. There were hardly any cars; yet the traffic was fierce, it felt aggressive, lawless, and loud.

My first morning in Varanasi was the hottest since I’d been in India. It was like breathing dishwater. As I edged along the outer walls of the buildings, pressed there by the furious flow of traffic through narrow streets tight-packed with bike rickshaws and motorbikes, the three-wheeled auto-rickshaws. There were hardly any cars; yet the traffic was fierce, it felt aggressive, lawless, and loud.

But I wanted to walk, to start off here on foot, not knowing where I was going. (Starting with a clear goal on this adventure had tended to lead to a circuitous route, anyway.) I fended off the rickshaw drivers who followed me, offering to show me the sights of the city: “Come . . . this way, madame . . . here, please, come . . . this way to the burning place.” I assumed they meant the famous cremation pyres by the Ganges, the must-see for travelers. I wasn’t ready yet to see bodies burning; I wanted to get a sense of where I was first.

Once out of the area of the thickest crowds, I took one branching lane after another, peering into doorways, hole-in-the-wall vendors’ stalls, nodding at people who stared blankly at me, watching me pass. The city seemed dense and endless. The heat made New Delhi’s scorching sun feel mild.

Once out of the area of the thickest crowds, I took one branching lane after another, peering into doorways, hole-in-the-wall vendors’ stalls, nodding at people who stared blankly at me, watching me pass. The city seemed dense and endless. The heat made New Delhi’s scorching sun feel mild.

It was almost noon when I came out onto the bank of the river, finally here after my twelve-year wait. On the far edge of the city near the end of the famous stone bathing ghats, the paved stairstep bank rose from the water up to the center city’s lanes. Before me lay the Ganges. Personified in scripture as the goddess Ganga, purifier, cleanser of sins. The river seemed flattened by heat, stretching out wide, bluish-gray-faint-green to the empty white sand and distant forest on the opposite shore. And quiet; it was hours past the early morning ritual baths.

I picked my way down the big stone steps to the water, each the equivalent of two to three ordinary stairs that drop to the river for several stories. No one was close by, a few people were here and there at a distance. Not only was I out of the crowd, I was alone. Halfway down the ghat, I saw to the left the longed-for postcard view: the whole curve of river shore, the ghats reaching down to the water, the spires of temples and domes of a mosque, the massive riverfront palaces. The sight seemed to float before me, seemed less real the longer I stood looking at it. It’s too still, feels unnatural, inhuman. Staring, I waited for something to move, but the heat seemed to have burned the city into a brilliant still photograph, now fixing an image of me onto that same photographic plate.

Finally I stirred myself into motion, turned to take a closer look at the water, inches from where I stood, sliding smoothly along the concrete lip of the ghat. This is the holy river: dirty, garbage floating at the edge, dead garlands of flowers, and what looked like household trash.

Walking along the edge, I crossed to the next ghat, the next set of steps, passed a pipe trickling a sewage-smelling liquid, and walked on for maybe five hundred yards. Still no sign of people or movement, and the center of the city seemed a far-distant painting I was walking toward. The riffle of the water’s edge and a bird overhead made the stillness seem heavier and more absolute. There was no one to watch, nothing to do but go forward in the heat toward a seeming mirage. I didn’t like it. The river’s bobbing garbage, the weight of the heat, the silence felt wrong. Not sacred. Instead, creepy, the silence engulfing. I started a hurried climb to the top of the ghat, back toward street level.

At the top step, I plunged back into the traffic, glad to see it. I slid onto the bench of the first empty rickshaw, I told the man “Dasaswamedh,” the main riverbank bathing steps near the center of town, where I’d be able to see the river while surrounded by people and noise.

There, a second descent to the water. People busied themselves along the water’s edge, bathing, washing laundry; men rowed long open boats full of passengers; wide shade umbrellas sheltered the rupee-charging holy men I’d read about, ready to offer a blessing or keep an eye on a bather’s shoes.

A man stepped up beside me, small and dapper with a cocky air, a straight-backed and lofty bearing. “Would I like to have a boat ride?” His name was Biju; he spoke English. His sweetly complacent smile made him seem sure of himself and his welcome. Yes, a boat ride would be fine. Without further discussion, it became clear that he was to be my companion for the afternoon. From the bank, we stepped from boat to boat to reach the one farther out where Biju’s oarsman waited in a long wooden open rowboat, like all the others. We set off down the river, the boatman, shirtless, pulling on long bamboo paddles.

Garbage floated past the side of the boat: a coconut, pieces of charred wood, unrecognizable bits of stuff. The water sloshed past, gray and sudsy. “It looks dirty,” Biju said, “but push that aside,” sweeping away bits of trash, “and you see it is clean.” He scooped up water in his cupped hand to show me.

We slipped past the walled edge of a ghat. Here close before me is Manikarnika, “the burning place,” the funeral pyres. On three tall fires near the water’s edge, three bodies were burning. I could make out their horizontal outlines. The boatman stopped rowing so I could look. One who dies in this city and gives the ashes to the Ganges becomes part of the eternal and is freed from the cycle of earthly rebirths: that is the Hindu belief. Two more bodies, freshly dead, wait, each wrapped tightly in thin silk, still lying on the bamboo ladder on which the body was carried here. Both have been lowered into the river’s edge, Biju said, and then left in the sun to dry before burning. The shapes of faces, limbs, knuckles, feet, showed through the silk. One was wrapped so tightly I could see the nose, the hollows of mouth and cheeks and eyes. If they had been alive, they would have suffocated.

Wrapped up and disposed of: this is what happens and we have no choice in the matter at all.

Within a new pile of firewood, a cloth-bound body lay still untouched, the kindling beneath just beginning to burn. From the end of the next pyre, I saw what looked like two feet sticking out. Or was it two pieces of wood, bent at the ends? I didn’t want to ask Biju; it seemed prurient to want to know. Whatever they were, I watched as they caught fire and began to burn, turning slowly from “toes-up” to twisted-to-the-side to downward-turned.

I yearned for one of the silk-wrapped figures to stand up, alive and enraged, throwing off the wood, stamping out the flames. I wanted to wake them myself, shout at them to get busy protecting themselves. But the bodies weren’t going to wake up. A pair of human feet blistered, seared, turned to fat, to charred sticks, then ash, as people stared. The spirits of these dead may indeed have been released from further human pain and worry. In that moment, I didn’t find that comforting.

The sound of a chant cut through the air from the top of the ghat and another body came into view, up high at city-level, at the top of the stone stairs. Four young men carried the stretcher calling out a sing-song, “Rama nama. . . .” A two-line chant with a marching beat: “Ra . . . ma . . . na . . . ma . . . Sa . . . tya . . . hai.”

“Rama nama. . . .” Again and again.

I knew what the words meant: “Rama is the true name, the name of God is truth.” The tone and rhythm were alluring. I rocked from the waist to that beat.

Down the steps to the water four men lower the body in. It floated. They splashed water over it to make sure it was completely covered, then they pulled it out to dry on the steps with the other wrapped corpses.

A few yards back from the water, a near-naked man wearing only a loincloth rushed about, through the smoke and haze of burning, tending the flaming pyres, a man of the once-untouchable caste, the Doms, who do this work. Yet another pyre flared, ignited with a blazing bundle of twigs waved in circular motion, the flame taken from fire that has been burning at this site for hundreds of years.

The groups of men standing at the edge of the ghat showed no obvious signs of grief. Such a display is said to cause bad fortune for the dead. There were no women in sight. “Women,” Biju said, “do not want to see their husband or their child burn.”

How could anyone stand and watch? I stared at those solemn groups of impassive men, thinking of my husband’s long narrow feet. My other people, family, friends. . . . A spin of faces.

Before we left the burning ghat, Biju pointed to the tall buildings that rose around us. “That is where widows may come to live out the rest of their lives.” The structures looked like Venetian tenements, dirty pastel with balconies on every floor. I imagined passing years up there in dim rooms, listening to the chant of the corpse-bearers arriving. “And there,” Biju said, nodding to another, “that building is for the dying to spend their last days.” Those windows also opened onto the sight of the burning, the gray mounds of ash and rubble shoveled to the edge of the river. I saw no faces or any sign of motion up there.

Biju glanced back at my face, saw I’d had enough, and signaled to the boatman to move us on. Minutes later, rowing, taking us away from there, the boatman accidentally let an oar slip out of his hand, into the river. Carried quickly out of his reach, it came toward me, where I sat near the back of the boat. Leaning over the side, I grabbed it, passed it back to him, dripping. The man stared at me, shocked, as if what I’d done was astounding. Perhaps he didn’t expect much from tourists. I gave my hand a wipe on the long blouse of my salwar kameez, childishly pleased with myself that, without hesitation, I reached into this monstrous holy river. It was now baptized—this hand—dipped halfway to the elbow in the gray-green water I had never meant to touch, so murky, full of garbage, laundry soap, bits of charred bone, and human ash.

*All photographs taken by the author

You were very brave to take such a journey on your own. It sounds fascinating. I would never be able to do it, however. The culture-divide is too wide.

Amazing and beautiful, Peggy. Thank you.

Thanks, Kenju. That three months told me what “trip of a lifetime” means. It was like an extra life for me.

Thank you, my sister South Writ Large contributor!

It seems the death rituals of alien cultures leave a much more indelible imprint than our own. I have witnessed the funeral pyres at a place fairly close to Varanasi. I have not seen an Inuit floated off on a glacier. But I suspect putting a corpse in a coffin, digging a hole , dropping the coffin in that hole, and covering it up would cause shock in certain populations. It’s in the eye of the beholder. I don’t think I have ever seen this demonstrated more succinctly than in India. A cohort of mine, in a bit of a condescending tone , asked an Indian acquaintance why cows were not eaten in India. The answer was immediate -“Why don’t you eat horses in America”?

Good point, Ron. I’m hoping for a burlap bag myself.

Baptism by fire, I’d say! I have recently learned that cremains are not biodegradable, as previously believed. The biodegradable components are burned off in the process. So cremains contribute mightily to the pollution of the planet. I wonder if this practice will change now that the Ganges is a protected entity with supposedly the same rights as a human being. In which case, there must be a commitment down the line to clean it up. You may have to make another trip to re-investigate!

Sounds to me like you’re the one to do the next investigation, Rea Nolan Martin!

Peggy…Another wonderful job..Beautifully written…

Thanks, Miller, and thanks for your patience.