The Boy in the Tree

South Writ Large communicated with Elizabeth Spencer following her recent publication.

SWL: What strikes you as the most radical change in today’s South compared to the world you grew up in?

ES: I did live apart from the South for many years in Canada principally, but I was always in touch and being wracked by the troubles of integration in the 1960s and also by the terrible havoc of Hurricane Camille. I viewed these events from afar, but I anguished over them. Moving to Chapel Hill one finds a very intelligent, educated community in a nest of various universities and (until recently) an enlightened political life. I am especially pleased to see African Americans in high positions, with no one remarking on this being even extraordinary. When I taught at UNC for six years until 1992, I found students of different racial backgrounds, competing without prejudice.

SWL: You were actively engaged in bringing about change in your day. What is your single proudest accomplishment?

ES: I’m flattered you want my opinion on such important topics when there are much more enlightened people than myself to ask. If you mean I was actively engaged in change, you must be referring to my novel The Voice at the Back Door, which attempted to take a realistic look at the black/white events in a small Mississippi town. This book’s popularity and world-wide exposure made me feel I must have succeeded to some extent in shining a light on what was all but forbidden territory for fiction at that time.

***

Excerpted from the short story collection Starting Over (Liveright Publishing Corporation, January, 2014)

On a February afternoon, Wallace Harkins is driving out of town on a five-mile country road to see his mother. He was born and raised in the house where she lives, but the total impracticality of keeping an aging lady out there alone in that large a place is beginning to trouble him.

His mother does not know he is coming. He used to try to telephone, but sometimes she doesn’t answer. She will never admit either to not hearing the ring, or to not being in the mood to pick up the receiver, though one or the other must be true.

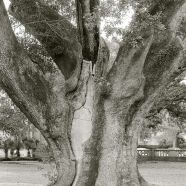

At the moment Mrs. Harkins is polishing some silver at the kitchen sink. At times she looks out in the yard. In winter the pecan trees are gray and bare—a network of gray branches, the ones near the trunk large as a man’s wrist, the smaller ones reaching out, lacing and dividing, all going toward cold outer air. Sometimes Mrs. Harkins sees a boy sitting halfway up a tree, among the branches. Who is he? Why is he there? Sometimes he isn’t there.

She often looks out the back rather than the front. For one thing the kitchen is in the back of the house, so it’s easy. But for another, there is expectation. Of what? That she doesn’t know. Of someone? Of something? Strange mule, strange dog, strange man or woman? So far lately there has only been the boy. When her son Wallace appears out of nowhere (she hasn’t heard the car), she tells him about it.

“Sure you’re not seeing things?” he teases.

“I do see things,” she tells him, “but the things I see are there.”

He hopes she’ll start seeing things that aren’t there in order to talk her into a “retirement community.”

“You mean a nursing home,” she always says. “Call it what you mean.”

“It isn’t like that,” he would counter.

“There isn’t one here,” she would object.

“Certainly there is. Just outside town. Two in fact, one out the other way.”

“If I was there I wouldn’t be here.”

That was for sure. Once, over another matter, she had chased him out of the house waving the broom at him. She was laughing, to show she didn’t really mean it, but then she dropped the broom and threw an old cracked teacup, which caught him back of the right ear and bled. “Oh, I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry,” she said. And ran right up and kissed where it bled. But she was laughing still, the whole time. How did you know which she meant, the throwing or the kissing?

He dared to mention it to his wife Jenny when he got home. His mother and his wife had been at odds for so many years he believed they never thought of it anymore, but when he said, “Which did she mean?” his wife said immediately, “She doesn’t know herself.”

“You think she’s gone around the bend?” he asked, and thought once again of the retirement home.

“I think she never was anywhere else,” Jenny answered, solving nothing. She was cleaning off the cut and dabbing on antiseptic which stung.

His problem was women, he told himself. But going up to his office that morning, he almost had a wreck.

The occasion was the sight of a boy standing on a street corner. It was the division of crossing streets just after passing the main business street and just before the block containing the post office and bank. The boy was wearing knee britches, completely out of date now, but just what he himself used to wear to school. They buttoned at the knee, only he had always found the buttons a nuisance, the wool cloth scratchy, and had unbuttoned them as soon as he got out of sight of his mother. As if that was not enough, the boy was eating peanuts! So what? he thought, but he knew the answer very well.

He himself had stood right there, many the day, and shelled a handful of peanuts, raw from the country, dirt still sticking to their shells. He always threw the shells out in the street. At that very moment, he saw the boy throw the shells in the same way. Wallace almost ran into an oncoming car.

Once at the office, he was annoyed to find a litter of mail on his desk. Miss Carlton had not opened the envelopes and he was about to ring for her when she entered on her own, looking frazzled. “They all came back last night,” she said. “I stayed up till two o’clock getting them something to eat and listening to all the stories. You’d think deer season was the only time worth living for.”

“Kill anything?” he asked, more automatically than not. He’d never been the hunting-fishing type.

“Oh, sure. One ten-pointer.”

Was that good or bad? He sat slitting envelopes and had no reaction, one way or the other. He had once owned a dog, but animals in general didn’t mean a lot to him.

The peanuts had been brought to him in from the country almost every day by a little white-headed girl who sat right in front of him in study hall. Once he’d found her after school, waiting for a ride (they both had missed the bus), and they went in the empty gym and tried making up how you kissed. Had she missed the bus on purpose, knowing he’d be late from helping the principal clean up the chemistry lab? How did she ever get home? He never found out for it was not so long after that he had been taken sick.

They took him home from school with high fever. Several people put him to bed. It lasted a long time. His mother was always there. Whenever he woke up from a feverish sleep, there she’d be, right before him in her little rocking chair, reading or sewing. “Water,” he would say, and she would give him some. “Orange juice,” he said, and there it would be too.

He told his wife later, “I can’t figure out how you can be sick and happy too. But I was. She was great to me.”

“You like to be loved,” his wife said, and gave him a hug.

“Doesn’t everybody?”

“More or less.”

When he went back to school the white-headed girl had left. Died or moved away? Now when he thought of her, he couldn’t remember.

***

Wallace Harkins was assured of being a contented man, by and large. When troubles came, even small ones looked bigger than they would to anyone with large ones. Yet he often puzzled over things and when he puzzled too long he would go out to see his mother and get more puzzled than ever. As for his state of bliss when he was sick as a boy and dependent on her devotion, he would wonder now if happiness always came in packages, wrapped up in time. Try to extend the time, and the package got stubborn. Not wanting to be opened, it just sat and remained the same. You couldn’t get back in it because time had carried you on elsewhere.

It was the same with everything, wasn’t it? There was that honeymoon time (though several years after they married, it had seemed like honeymoon) when he and Jenny got stranded in Jamaica because of a hurricane, no transport to the airport, no airport open. Great alarm at the resort hotel up the coast from Montego Bay, fears of being levelled and washed away. They ate by candlelight, and walked clinging to one another by a turbulent sea. “Let’s just stay here,” was Jenny’s plea, and he had shared it. Oh Lord, he really did. But then it was over. When he thought of it, wind whistled around his ears, and out in the water a stricken boat bobbed desperately. They both had loved it and tried going back, but this time the food was dreary, the rates had gone up, and the sea was full of jellyfish.

***

“Mother,” he asked her, “why do people change?”

She was looking out the back window. “Change from what?”

He’d no answer.

“How is Edith?” she asked. Edith was his daughter.

“Edie is failing Agnes Scott,” he said. “She isn’t dumb, she just doesn’t apply herself.”

“Then take her out for a while. Start all over.”

I’ll do that, he thought. Time marched along. He had gray in his hair.

“Do you remember Amy Louise?” he asked, for the name of the white-haired girl had suddenly returned to him.

“That girl that came here and ate up a lot of candy once? It was when you were sick. I thought she’d never seen any candy before. Before she left, she had chocolate running out of her mouth.”

“Did she have white hair?”

“No, just brown. You must mean somebody else.”

He noted the street corner carefully when he drove home. Nobody was on it.

***

Wallace had always loved his wife Jenny from afar. When they were in high school together she hadn’t the time of day for him, and the biggest of life’s surprises came when years later she consented to marry him. “She’s just on the rebound,” said an unkind friend, for, as they both knew, she had been dating an ex-football player from State College, while working in Atlanta. “Just the same,” said Wallace, “she said she would.”

***

Jenny liked any number of things—being back in the town, a nice place to live, furniture to her taste, cooking and going on trips. She was easy to please. She even liked him in bed. Surprise? It was true that his desires were many, but realizations few. He had put himself down as a possible failure. With Jenny, all changed. She didn’t object when for a warm-up he fondled her toes. She said it was better than tickling her. Who had tickled her? He didn’t ask.

Jenny was pretty, too. Shiny brown hair and clear smooth skin. He loved the bouncy way she walked and the things she laughed at. He told his mother that. She said that was good. But when he asked if she didn’t agree, she didn’t answer. But actually anybody in their right mind would have to agree, thought Wallace. He caught himself thinking that. Was his mother not in her right mind? A puzzle.

“She makes you feel guilty,” Jenny pointed out. “If I were you, I’d quit going out there so much. She’s happy the way she is. If you didn’t come, she wouldn’t care.”

“Really?” said Wallace. The thought pierced him, but he decided to try it.

***

About this time, Wallace had a strange dream. Like all his dreams, it had a literal source. Out in Galveston, Texas, a man had acquired a tiger cub, a playful little creature. It grew up. One summer day, responding to complaints from the neighbors, the animal control team found a great clumsy orange-colored beast chained in the backyard of an abandoned house. The chain was no more than three or four feet long and was fastened to an iron stake sunken in concrete. In fact, the only surface available to the animal was cement, the yard having been paved for parking. The sun was hot. The tiger at this stage resembled nothing so much as a rug not even the Salvation Army would take.

Reading about it, Jenny was riveted to the paper. “Where’s the bastard took that cat in the first place?”

“They’ll track him down.”

“I hope they shoot him,” she said.

“You don’t mean the tiger?” Wallace teased her. She said she certainly didn’t.

What do you do with a tiger?

The event made headlines locally because a preserve for large cats was located near their town. A popular talk show host agreed to the tiger’s expenses for transportation, release, rehabilitation, psychiatric counseling, and nourishment.

“Good God,” said Wallace, “they’re going to have to slaughter a whole herd of cattle every weekend.”

“Maybe it will like soybean hamburgers,” said Jenny.

“Wonder if they ever found that guy.”

“I’ve just been wondering if maybe the tiger ate him.”

In his dream, some weeks later, Wallace looked out the back door window and saw the tiger, thoroughly cured and healthy, wandering around in the backyard. He went out to speak with it. He thought he was being courageous, as it might attack. At first it glanced up at him, gave a rumble of a growl, and wandered away, as though bored. “You bastard,” said Wallace. “Don’t you appreciate anything?” Then he woke up.

***

The definitive quarrel between Jenny and Mrs. Harkins had taken place rather soon after Wallace’s marriage. They were in the habit of going out to see the lady on Sunday afternoons and staying for what she called “a bite to eat.” Sometimes she made up pancakes from Bisquick mix. Jenny was holding an electric hand beater and humming away on the batter when the machine slipped out of her hand and went leaping around first on the table, where it overturned the bowl with batter, then bounced off to the floor. Jenny shouted, “I can’t find the fucking switch!” The beater went bounding around the room. She was trying to catch up with it, but found it hard to grab. Batter, meantime, soared around in splatters. Some of it hit the walls, some the ceiling, and some went in their faces and on their clothes. Mrs. Harkins jerked the plug out of its socket. Everything went still. Jenny licked batter off her mouth and grabbed a paper towel to mop Wallace’s shirt. A blob had gone in Mrs. Harkins’ hair. Jenny got laughing and couldn’t stop. It seemed a weird accident. “I guess the shit hit the fan,” she said.

Mrs. Harkins walked to the center of the room. “Anybody who uses your kind of language has got no right to be here.”

“Mother!” said Wallace, turning white.

“Gosh,” said Jenny, turning red. She walked out of the kitchen. There fell a silence Wallace thought would never end. He expected Jenny back, but then he heard the car pull out of the drive and speed away.

Mrs. Harkins set about cleaning pancake batter off everything in sight, and scrambled some eggs for their supper.

“I think you both ought to apologize,” Wallace ventured, when his mother drove him home.

“You do?” said Mrs. Harkins, rather vaguely, as though unsure of what he was talking about.

“I never heard her say words like that before,” Wallace vowed, though in truth Jenny did have a colorful vocabulary, restrained around Edith. In the long run, nobody apologized. But Jenny wouldn’t go back with Wallace anymore. What she saw in her mother-in-law’s announcement was that she (Jenny) was a lower-class woman, common, practically a redneck. “She didn’t mean that,” said Wallace. “You can’t tell me,” said Jenny. Furthermore, she thought the results were exactly what Mrs. Harkins wanted. She didn’t want to see Jenny. She had been waiting all along for something to happen.

Within himself, Wallace lamented the rift. But he finally came to consider that Jenny might be right. He took to going alone to see about his mother. Gradually, this change of habit got to be the way things were. In routine lies contentment.

***

After the tiger dream Wallace went back again. He didn’t know why, but felt he had to.

She wasn’t there. The house still quiet and empty, she had even remembered to lock the door. The car was gone. He scribbled a note asking her to call him and went away reluctantly. She could be anywhere.

Wallace returned home but heard nothing. He fretted.

“Well,” said his mother the next day (she hadn’t called). “It was just that boy up in the tree. I finally went out and hollered up to ask him who he was and what he wanted. Then he came down. He just said he liked being around this house, and he wanted me to notice him. He was scared to knock and ask. He rambles. He’s one of those rambling kind. Always wandering around in the woods. I drove him home. The family is just ordinary, but he seems a better sort. Smart.” She tapped her head significantly.

“I dreamed about a tiger,” said Wallace.

“What was it doing?” his mother asked.

“Prowling around in the backyard. It’s that one they brought here from Texas.”

“Maybe it got out,” she suggested.

If only I could stick to business, thought Wallace.

***

That weekend Edith came home from Agnes Scott. She had flunked out of math courses, so could not fulfill her ambition to take a science major, a springboard into many fabulous careers, but had enrolled instead in communications. She had a boyfriend with her, a nice well-mannered intelligent boy named Phillip Barnes, who in about thirty minutes of his arrival had made up for Edie’s inability to pass trigonometry. He knew how to listen to older people in an attentive way. He let it drop that his father ran a well-known horticultural company in Pennsylvania, but his mother being Southern had wanted him at Emory. He was working on his accent with Edie’s help, he claimed, and did imitations to make them laugh, which they gladly did. He was even handsome.

Wallace, feeling proud, suggested they all go out to see Grandmother. Edith exchanged glances with her mother. “She won’t know whether we come or not. Anyway, the house is falling down.”

“She remembers what she wants to,” said Wallace.

“He’s got an Oedipus complex,” said Jenny.

They argued for a while about such a visit but in the end Wallace, Edith, and Phillip drove out on the excuse that the house, at least, was interesting, being old.

On return they announced that Mrs. Harkins had not said very much, she just sat and looked at them. “Not unusual,” said Jenny.

Wallace sighed with relief. For, as a matter of fact, the little his mother had said

had been way too much. She appraised the two for some time, sitting with them in the wide hallway, drafty in winter, but cool in spring and summer, and remarked that a bird had flown in there this morning and didn’t want to leave. “I chased him out with the broom,” she said. Wallace well remembered that broom and wondered if she had made it up about the bird. Mrs. Harkins closed her eyes and appeared to be either thinking things over or dozing. Phillip Barnes conversed nicely on with Wallace.

Mrs. Harkins suddenly woke up. “If you two want to get married,” she said, “you are welcome to do it here.”

They all three burst out laughing and Edith said, “Really, Grandmamma, we haven’t got halfway to that yet.”

“You might,” said Mrs. Harkins, and closed her eyes again.

“It really is a fine old house,” said Phillip, who appreciated the upper-class look of old Southern homes.

Going out to the car, Wallace whispered to Edith not to mention what his mother had said. “You know they don’t get on,” he said.

But Phillip unfortunately had not heard him. Once back home, he laughed about it. “Edie’s going to come downstairs in a hoop skirt,” he laughed. But seriously, to Wallace, he said: “Gosh, I do like your mother. She pretends not to be listening, but I bet she hears everything. And what a great old house that is. Thanks for taking us.”

“What’s this about a hoop skirt?” Jenny asked.

“Oh, nothing,” said Edie.

But Phillip wouldn’t stop. It seemed that Phillip didn’t ever stop. “She said Edie could get married out there. Can’t you just see her, carrying her little bouquet. Bet the lady’s got it all planned.”

***

No sooner were Edie and Phillip on the road to Atlanta than Jenny threw a fit. “What does that old woman mean?” she demanded. “She’s doing what she always does. She’s taking over what belongs to me!”

“But honey,” Wallace said, “we don’t even know they’re apt to get married.”

“They’re in love, aren’t they? Anything can happen. And don’t you honey me.”

“But sweetheart, maybe Mother meant well. Maybe she saw an opportunity to get us all back together again.”

“With her calling the shots. She’s a meddlesome old bitch is what she is.”

That was too much. Wallace had looked forward to an evening with Jenny, going over the whole visit a piece at a time, and afterwards having a loving time in bed. He wasn’t to have anything of the sort tonight, he realized, and furthermore his mother was not a bitch.

“My mother is not a bitch,” he said, and left the house.

How was he to know that Jenny had been mentally planning Edie’s wedding herself? She had got as far as the bridesmaids’ dresses, and was weighing black and white chiffon against a medley of various colors, not having got to what the mother-of-the-bride should appear in.

Wallace wandered. He drove around in the night. He thought of the tiger but it was too late to look for the animal preserve. He thought of his mother, but he dreaded her seeing what was wrong. He’d no one to admit things to.

He went to a movie and felt sorry for himself. On the way out he saw a head of white-blonde hair going toward the exit. He hastened but there was only an older woman in those tight slacks Jenny disliked, wearing too much lipstick. He did not ask if her name was Amy Louise.

***

In spring Wallace threw himself madly into his work. He journeyed to Atlanta to an insurance salesmen’s conference, he plied his skills among local homeowners, car owners, small business owners. He even circulated in a trailor park and came out with a hefty list of new policies. What is it that you can’t insure? Practically nothing.

Then, to his surprise, the way opened up for Wallace to make a lot of money. He received a call from some leading businessmen who wanted to talk something over. A small parcel of wooded land his father had left him just beyond the highway turnoff to the town was the object of their inquiry. Why didn’t he develop it? Well, Wallace explained, he’d never thought about it. The truth was, in addition, he connected the land with his father who had died when Wallace was eleven and whom he did not clearly remember. The little seventy-five or so acres was not pretty; it ran to irregular slopes and the scrappy growth of oaks and sycamore could scarcely be walked among for all the undergrowth. Still, Wallace paid the taxes every year, and thought of its very shaggy, natural appearance with a kind of affection, a leftover memory of his father, who had wanted him to have something of his very own. And he did go and walk around there, and though he came out scratched with briers, it made him feel good for some reason.

“Honey, we’re going to be rich,” Wallace said to Jenny.

“Why else you think I married you?” Jenny giggled, perking up.

Still what surprised him was his popularity. Prominent men squeezed his hand, they slapped his shoulder, they inquired after his mother, they recalled his father.

“Why do they like me?” he inquired of Jenny.

“Why not?” was Jenny’s answer.

But he thought what it all had to do with business. And he was still puzzling besides over what had happened at the last business meeting. For they had succeeded with him; he was well along the road. Subdivision, surveys, sewage, drainage, electric power . . . But suddenly he had cried out:

“To hell with it! I don’t want to!”

He sat frozen, wondering at himself, and looking about at the men in the room. They had kept on talking, never missing a syllable. On leaving, he had asked one of the oldest, “Did I say anything funny?” “Funny? Why no.” “I mean, didn’t I yell something out?” “Nothing I heard.” So he’d only thought it?

Standing in the kitchen that night, Wallace came across the real question in his life. He scratched his head and thought about it.

“You and Edie, do you love me?”

“You like to be loved,” Jenny said, and patted his stomach (he was getting fat). She stroked his head (he was getting bald). She had calmed down since her explosion, but they both still remembered it and did not speak of it.

***

The trees were in full leaf when he next drove out to see Mrs. Harkins.

The front door was open but no one seemed to be downstairs. He stood in the hallway and wondered whether to call. From above he heard the murmur of voices, and so climbed up to see.

His mother was standing in one of the spare rooms. With her was a boy, maybe about fifteen. A couple of old leather suitcases lay open on the bed, the contents partially pulled out and scattered over the coverlet. She was holding up to the boy a checkered shirt which Wallace remembered well, a high school favorite.

“Isn’t it funny? I never thought to give away all these clothes?” she said.

The boy was standing obediently before her. When she held up the shirt he drew the sleeve along one arm to check the length. He was a dark boy, nearly grown, with black hair topping a narrow intelligent face set with observant eyes. Truth was he did measure out a bit like Wallace at a young age, though Wallace had reddish brown hair and large coppery freckles. They stared at each other and thought of nothing to say.

“This is Martin Grimsley,” said Mrs. Harkins. “Martin, this is my son Wallace.”

“The boy in the tree?” Wallace asked.

“The same,” said Mrs. Harkins, and held up a pair of trousers which buttoned at the knee. “Plus fours,” she said. “Too hot for now, but maybe this winter.”

She had made some chicken salad for lunch with an aspic, iced tea and biscuits and banana pudding. Wallace stayed to eat.

“Wallace saw the tiger,” said Mrs. Harkins.

The boy brightened. “They keep him out near us with all them others.”

“All those others,” said Mrs. Harkins.

“I can hear ’em growling and coughing at night.”

Wallace asked: “Did you stand on a corner uptown eating peanuts?”

“Not that I know of,” responded Martin Grimsley.

They lingered there on the porch while the day waned.

Martin Grimsley talked. He talked on and on. He had been up Holders Creek to where it started. He had seen a nest of copperheads. Once he had seen a rattlesnake, but it had spots, so maybe it wasn’t. He liked the swamps, but he especially liked the woods, different ones.

Inside the telephone rang. Nobody moved to answer it. They sat there listening to Martin Grimsley, until the lightning bugs began to wink, out beyond the drive.

“Someday we’ll go and see,” said Mrs. Harkins.

“See what?” said Wallace.

“The tiger,” said the boy. “She means the tiger.”

“Of course,” said Mrs. Harkins.

They kept on talking about the countryside. Wallace wandered with them, listening. He watched the line of the woods where the property ended. There the girl with silver hair would appear, the tiger walking beside her.

He was happy and he did not see why not.

Reprinted from Starting Over: Stories by Elizabeth Spencer. Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Spencer. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation.