The Blue Marble. http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view.php?id=57723Earth Western Hemisphere

Share This

Print This

Email This

The Dual Citizen Experience

Picture yourself on a motorcycle weaving your way through the wine country around Cape Town, just a few miles off the Atlantic coast. Feel the breeze, smell the air, taste the freedom. That’s me after a meeting with the German ambassador to South Africa a few years ago. I had just finished high school in Germany and had gone abroad to study political science and sociology. I was experiencing this amazing sense of adventure—a sense that until very recently was reserved for a select few. In the past, traveling was for the rich, studying was for the elite, and doing both at the same time was for dandies or super-nerds. But now travel has become more affordable, and you can be in most places on the planet in less than a day. What a shift!

That day on my worn-out little motorcycle I was excited not only about the beauty and experience of South Africa, but also about the thoughts triggered by my meeting with the ambassador. In talking to him I realized that even those fancy diplomats whom I had revered from a distance were human beings and were living life just like everyone else. They went to school, they did their best at university, they worked hard and cared about their jobs and employers: in this case the Federal Republic of Germany. No magic involved. So I set about my quest to figure out how to enroll in the diplomacy programs of Germany and the United States, my two home countries. And that’s when it got complicated.

First, I went to my computer and googled everything I could find about these programs. I realized I would have to learn a non-Western language to qualify: Arabic, Chinese, or one of the hundreds of African languages, preferably Swahili. Difficult, but manageable. I would also have to demonstrate intercultural competence, solid general education, and the willingness to be sent to remote places in frequent rotation. My education was solid, I thought; my intercultural competence was existent, I assumed; and I was willing to be sent to remote places. I was in South Africa, after all.

Then I found a memo by the U.S. Foreign Service that made me realize that what I thought qualified me more than anything else—my dual citizenship—practically disqualified me for the program. The reason? I had voted in two different countries, so my loyalty was in question. I was very likely not going to survive the background check because of it. Since I had been a responsible citizen in both of my home countries, I had become a perceived threat to national security. I was shattered. Not just because of my diminished diplomatic prospects, but also because of the cultural message this sent. One of my home countries was saying I was dangerous because I felt responsibility for my other home country. Basically, one of my countries was jealous because we weren’t in an exclusive relationship.

This is not a helpful spot to be in when you’re trying to figure out who you are and what you’re called to do in this world. Other layers of my experience in South Africa added to the complexity. Because I had an American accent I was considered American even though my education had been German, my political socialization had been German, and most of my friends and much of my family was German. Suddenly my accent gave me my identity: that of a full-blooded American. I was challenged on the Iraq invasion, on American war crimes in Abu Ghraib, on the practiced torture in Guantanamo—it wasn’t easy to be an American abroad in the Bush Jr. years. Germany had not participated in the Iraq war because the intelligence provided to the United States by German intelligence wasn’t independently verifiable and wasn’t, therefore, enough to warrant going to war. Since I had lived in Germany during those years I didn’t feel a responsibility for America’s foreign policy toward the war. But here I was, seen as a direct representative of Cheney, Rove, and Rumsfeld. Clearly not where I wanted to be at this time of my life.

Although my time in South Africa was formative, it was also challenging. The rich and complicated experience of projection and transference was something akin to boot camp for living in a globalized world. I realized that being a dual citizen made folks from both countries feel as if the purity of my identity and motives were compromised. I was seen as half German and half American. But of course you want to be a full member of a group, you want to be a full participant in a culture, and a full citizen in a political process. So I tried to reframe how I thought about this clash of identities. I decided that I would refer to my dual citizenship not as a syncretic mélange of two half cups of coffee, but as a beautifully potent, yet wholesome and integrated double espresso.

Over time my desire to make sense of identities and borders in a complex globalized world took more systemic and theoretical shapes. Given the intercontinental nature of my family, my work with the Rwandan nonprofit Wikwiheba, and our second home base in South Africa, I knew that my identity would never become any simpler. I knew I would have to learn how to live in the multiple social and political structures I was placed in, and I set about to find ways of reframing them. Over time I realized that I was not alone in this feat. Hundreds and thousands of people around the globe are considering new ways of building institutions that better match the reality we live in. Many of these people I found in Europe through programs funded by the European Union.

One of these programs is called the Erasmus program. It helps students from member countries study abroad in another member country in the European Union. Almost half of the funded students have a nonacademic family background, which widens the study abroad experience from catering only to the wealthy elite to encompassing all levels of society. The impact is incredible. Millions of students have gone through the program. Almost all of the participants imagine living abroad in the future, and about a third of them find a life partner whose nationality is different than their own. During my research, I realized that since the conception of the program, a few decades ago, more than one million babies have been born in cross-border relationships made possible by programs like Erasmus. That’s 1,000,000 dual citizen babies! My experience wasn’t that unique after all. This makes cross-border identity a widespread phenomenon. From a weird fringe group, dual citizens are becoming a relevant cultural force. And their mere existence questions the kind of national border thinking we have cultivated since the conception of the sovereign modern state in the Enlightenment period.

For dual citizens most of the borders and boundaries we experience are fairly arbitrary, historically contingent lines drawn by human beings. Far from being essential to nature, the nation-state boundaries are utterly human, social constructions. This doesn’t make them irrelevant. On the contrary: these boundaries are powerful shapers of worldview. Using the metaphor of relativity theory one could call the presence of these constructs social carvers of time and space. These borders, and the identity constructed by the communities living within those borders, capture the imagination and form the lens we use to view reality. There are few better tools to illustrate this than the maps we use to guide our worlds.

Map as Guide

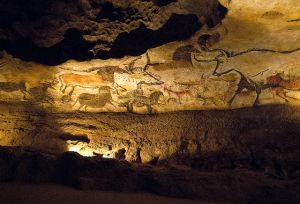

Interestingly, the first known maps did not illustrate land territory, but rather mapped the sky. The earliest maps we have access to were discovered by Dr. Michael Rappenglück from the University of Munich and were found in the caves of Lascaux, France, dating back to around 16,500 BC. He also discovered a star map in the Caves of Monte Castillo, Spain, dating back to around 12,000 BC. Of the map in Lascaux he told the BBC: “It is a map of the prehistoric cosmos. It was their sky, full of animals and spirit guides.” As I think about the map making through history, I’m struck by the way maps illustrate how people think about the order of that which is mapped and people look to that which is mapped as a guide through the medium of the map: Tell me what map you use and I’ll tell you who you are!

Map as Horizon

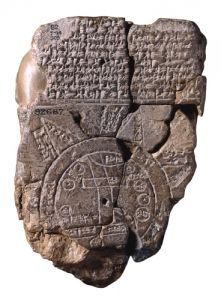

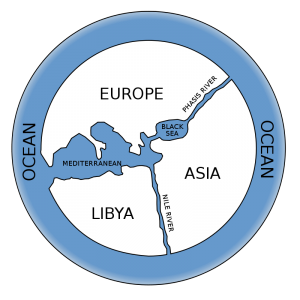

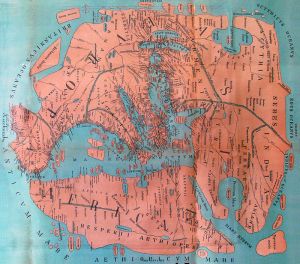

The first known map showing land is the Imago Mundi map from Babylonia, dating back to about 600 BC. The clay tablet illustrates how our maps demonstrate our horizon. The focus in this map is on Babylon, surrounded by Assyria and what today is Armenia. Similarly, the sixth-century-BC philosopher Anaximander depicted the known territories in his world on a simple map showing three big land masses: Europe, Asia, and Libya. At the heart of the map are the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea, and all the land is surrounded by ocean. The horizon here is the vast, never-ending water in the distance as viewed from Anaximander’s vantage point, present-day Turkey.

Map as Trinity

Anaximander’s map depicting the three distinct continents (Europe, Asia, Africa) dominated Greek cartography into the next millennium, as Pomponius Mela’s map shows. Cicero already described planet Earth as a small globe in a huge universe, but the visual horizon remained limited by the plate-like depictions of specific territories.

In the Middle Ages a number of beautifully designed plate-shaped maps were conceived―for example, the Ebstorf Map drawn in 1302 and Pietro Vesconte’s map of 1321.

The influence of neoplatonism’s focus on oneness and unity in complexity is visually apparent in all of them. The almost trinitarian-themed influence of the early Greek model with Europe, Asia, and Africa as three components of one round whole is also still present.

Maps as Perspective

When this cartographic trinity was broken up by the increased realization of the complexity and diversity of geography another interesting question was born: the question of perspective. A famous Chinese map from the fourteenth or fifteenth century depicts China at the center and Europe as merely an addendum. The trinitarian-like equilibrium of Europe, Asia, and Africa was broken.

Similarly, the Kangnido Map from Korea depicts Asia at the center with Europe at the eastern periphery. Korea’s proportion is overblown. This, as well as the fact that Japan’s mapping is far more accurate, shows a different perspective compared to the Chinese map. While the Korean map was designed mostly for decorative purposes, some cartographers started to design their maps for the purpose of accurate navigation. For example, the world map commissioned by the Portuguese king and designed by the Venetian monk Frau Mauro in 1459.

Map as Globe

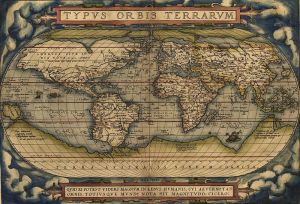

A massive change of perspective is brought by Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel—earth apple. Behaim made the earth visually tangible as a globe. Because Columbus had not yet returned from his travels to America, however, it was not depicted on the 1492 globe. The effect of the Copernican paradigm shift and the globe-like map illustrations are visible in what is considered the first modern atlas: the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum made by Ortelius in 1570.

This map, depicting the “Theater of the World,” is now fully conscious of the whole extent of land masses on the globe: North and South America and even Australia are included (although Antarctica and Australia are depicted as one).

Map as Science

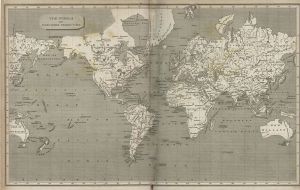

The Enlightenment and the renewed focus on mathematical precision brought about the Mercator projection and informed most of the cartography after Europe’s discovery of the Americas. This map from 1820 shows that little has changed in the overall setup, but the increased precision is clearly visible. Ortelius’s sixteenth-century mistake of showing Australia and Antarctica as one is remedied, and Australia is now correctly called “New Holland,” thus marking the colonial period.

Since much of the scientific cartography in this period was done by Europeans under the influence of the colonial experiments, Europe and North America are usually at the center of the map and are depicted as larger than they actually are (due to the equations and standards used).

Map as Power

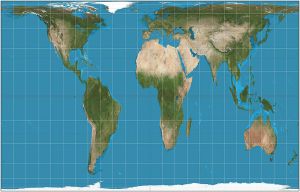

The nineteenth-century maps that served as the navigating tools for colonialist Europe are scientific in precision but far from neutral in orientation. The anticolonialist movement of the twentieth century therefore critiqued several of the basic conventions of Western cartography, for instance, by creating south-up maps like the one shown below.

James Gall and Arno Peters rendered a more precise projection of territory that more accurately depicted land proportions than the Mercator projection had.

One thing is clear: Maps are not ethically neutral. They carry a lot of normative weight and the power of cultural convention. And, who said north was up?

Map as Politics

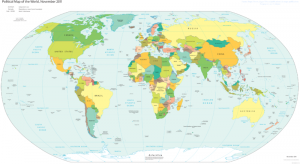

With the intellectual force of the Enlightenment and the catalyzing effect of the religious wars in the seventeenth century, the modern nation-state starts to emerge as a neutral state authority guaranteeing peace through a monopoly of force. By the late nineteenth century this system was established quite thoroughly in the Western world. This system was spread throughout the world by colonialism and dominated global politics until quite recently. In the twentieth century with its aggravated forms of globalized transportation and communication, as well as transnational migration and a wave of challenges beyond the immediate state level, a new way of living together has emerged on a global scale. Unfortunately, our political systems, and especially nation-state governments, struggled to keep up with the recent high-speed transformation of life on this planet. Although there is increased cooperation on the nation-state level, many of the significant challenges of our time, especially climate change and so-called asymmetrical warfare (like terrorism), remain unsolved by the nation-state. There is a gap between the way the world works and the way our governments operate. It becomes obvious that our traditional approaches to diplomacy and international problem solving are outdated when we look at the maps used in the political domain.

Except for a few revisions, this political map is simply a nineteenth-century map with minor upgrades, and this beautifully illustrates the current state of affairs: we are trying to solve today’s problems with yesterday’s solutions.

Map as Trend

When I saw a map published by Facebook a few years ago, I realized how powerful a tool mapping was for understanding and relating to our world. Facebook had asked a team of their designers to illustrate all the communication links between users using their platform. Fittingly, they left out all the nation-state borders and chose to simply draw lines between the users to show their connections. The following map was the result.

We learn several things from this map: First, China isn’t on Facebook. China has its own social media platform, and it uses its monopoly of force to make Facebook use very difficult for its ordinary citizens. So the nation-state clearly has not left all relevant spheres of life, as some globalization theorists imply. Second, we see how borders become increasingly irrelevant for the ways people express their stories to themselves and others. Citizenship is one form of identity, but there are many others. This complexity induces a new desire in some for simplicity. We want to make our life, our story, our systems uncomplicated again. These desires take different forms: political simplicity in fascism, religious simplicity in fundamentalism, and cultural simplicity in minimalism. But we all know that these forms of simplicity are based on a falsehood. The world is more complex. The world is more diverse. And it is more mysterious. Identity has moved toward the plural: it has become the stories we tell ourselves and others about ourselves and others, engaged in a never-ending dialogue and continuing conversation, however much we would like to receive a clear path, an easy solution. Whoever comes along to bait you with a simple way, beware.

Map as Identity

The struggles that come with new cultural tectonics in a global age with lots of cross-border flows, and some remnants of the old nation-state order, point toward the issue of identity, and yet another form of mapping emerges: identity maps that illustrate clichés and ways people simplify the cultural environment in order to gain a sense of stability in a complex world.

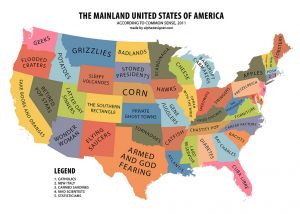

The Mainland USA According to Common Sense (2011). Authored by Yanko Tsvetkov. http://alphadesigner.com/

Half comedy and half cultural analysis, these maps actually help illustrate the different vantage points we bring to this fully global reality that we are more and more becoming conscious of.

Map as Transformation

One of the fundamental transformations in cartography was the map in globe form. Suddenly the tools used for navigation, both figuratively and literally, more or less matched the physical reality. But the maps used on these globes were largely for political purposes. A new, less obvious, but all the more powerful form of map came about when we developed the capability to take pictures of our planet from outer space. When you search online for “Earth” you are no longer only taken to simple two-dimensional world maps that depict political and geographical borders. A search for “Earth” delivers breathtaking pictures of a planet covered in green and blue and white that shows this huge and complex world from a bird’s eye perspective.

This bird’s eye perspective inspires immediate awe and in the context of the industrial destruction of our planet, it also triggers the desire to help preserve and protect this vulnerable, life-giving globe made of star stuff. This live map of planet Earth made possible by high-resolution space photography does not show any of the traditional boundaries and biases that are so obvious in our daily lives and the political arenas of the world. The subtle and powerful exposure to these images has sparked a widespread consciousness of the real and ultimate oneness that philosophers have talked about for millennia. What kind of political consequences will this new pictorial material have in the long run? Will it subvert some of the ways we use our maps? Will it destroy certain forms of maps altogether? Will it bring forth all kinds of new maps that we cannot even imagine right now? Our run through the history of cartography certainly suggests so. Because this history makes one thing very clear: Maps matter. And they are both shaped by humans and are shaping humans. So to be engaged in finding maps that best map the world we find ourselves in is to be engaged in being shaped by and actively shaping humanity.

Our task today is to find new paths of meaning for a healthy, holistic life without falling prey to the seductive power of simplicity. The world is complex. The world is challenging. And much about our world is in fact mysterious. The answer to this complexity, I believe, lies in a new appreciation of mystery and the honest acknowledgment of our mortality. We do not know it all. We do not have easy answers. We do not live in total certainty. But once we can tolerate the ambiguity of this complexity, new life can emerge, new avenues will open, and new faith can unfold. It is the multiplicity of sound and voice and utterance that gives rise to a new world and to new beginnings. Grounded in tradition and open for the future, we can embrace the change without losing our home. For whether we like it or not, we are all citizens of multiple dynamic worlds. We all remain members of the past, we all are actors in the present, and we all will be humans of the future.

This simply a brilliant piece of work! It is personal and it expands in application from an expanding category of world wide citizens to everyone anywhere. Jonas has profound insights about matters to which I would suppose that most of us have not given much thought, and in offering these insights convinces us about what we should be thinking and learning — not only in today’s duel crisis due to globalization and a technological revolution, but philosophically and spiritually.