Many of the lazy rlackwater rivers in eastern North Carolina serve as home to wintering waterfowl. Waterfowl like these tundra swans can be found on the rivers and creeks of the Albemarle Peninsula from December through February.

Share This

Print This

Email This

On the Shoulders of a River

Rivers don’t rely on cities for their existence, but in every state and nation, the history and survival of our cities is integrally related to one or more rivers. When we study world history the names London and the Thames, Paris and the Seine, Cairo and the Nile, and Baghdad and the Tigris-Euphrates are inseparable. New York City exists because of the Hudson River and the natural harbor created where it meets the Atlantic. Boston thrives because of two rivers, the Charles and the Mystic, and the safe harbor created at their juncture. In the Deep South, Charleston was born and still thrives at the confluence of the Cooper and the Ashley. You can do the rest of the American parings in your head: Savannah and the Savannah River, Washington and the Potomac, New Orleans/Memphis/St. Louis/Minneapolis on the Mississippi, and so on.

The connection is the same with our great desert metropolises—cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix. Although they did not grow up on the banks of a river, Las Vegas and Phoenix exist only because they created long straws to suck water from the Colorado or other far away rivers. Los Angeles imports 85 percent of its water needs from distant sources.

The Cape fear River tumbles out of North Carolina’s Piedmont near Raven Rock State Park. The river is a corridor for people, wildlife and commerce. North Carolina’s port city on the Cape Fear is Wilmington.

Here in the Tar Heel state, and in the South, there is a river in the story of every town. Wilmington emerged out of the high ground near the mouth of the Cape Fear River. New Bern was established at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent at the southern end of the Pamlico Sound. Washington (a.k.a. “Little Washington”) flourished near where the Tar-Pamlico River flows into Pamlico Sound. Three rivers—the Roanoke, Chowan, and Pasquotank—flow into the Albemarle Sound, and each river is home to important cities formed in the 1700s. The towns of Plymouth, Williamston, and Roanoke Rapids flourished on the banks of the Roanoke. One of North Carolina’s colonial capitals, Edenton, would not exist but for the Chowan, and today’s largest city in the northeastern corner of the state, Elizabeth City, owes its existence to the Pasquotank River.

Washington, NC was established at the mouth of one of North Carolina’s great rivers, the Tar-Pamlico River, where it flows into Pamlico Sound.

In North Carolina’s Piedmont, the Eno River nourished the growth of Hillsborough and Durham, before joining with the Flat River to form the Neuse. Raleigh, the capital city, sprawls over several rivers, but much of its growth and prosperity in recent decades can be attributed to its proximity to the Neuse River and its major tributary, Crabtree Creek. It is between two rivers, the Deep and the Haw, that Greensboro got its start. As the Haw flowed southeast across the Piedmont, it powered the growth of manufacturing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Burlington and Saxapahaw. Just to the west of the Haw River, the Deep River flowed past High Point, through North Carolina’s forgotten coal mining region in Chatham County, before supplying water to the great Civil War and Reconstruction iron furnace at Endor in Lee County. Many are unaware that the Haw and the Deep merge to form the mighty Cape Fear River just before it tumbles out of the Piedmont and begins its lazy easterly journey past Fayetteville. The Cape Fear did the heavy lifting and floated barges laden with pitch, pine tar, and lumber (extracted from longleaf pine savannas) to the pre−Revolutionary War port of Brunswick Town and to its successor, Wilmington. For me, however, the Cape Fear is equally important for lesser-known rivers in its basin, including the Northeast Cape Fear and the magnificent Black River—home to one of the oldest and largest stands of bald cypress in eastern America.

The Black River, a tributary of the Cape Fear, is one of North Carolina’s most beautiful waterways. It is also home to many of the oldest bald cypress trees in eastern America–with some specimens found to be nearly 1700 years old.

Finally, it can be said that a river, or river feature, has predetermined the existence of many towns and cities in North Carolina. A good example is the Catawba River, which falls off the Appalachian escarpment east of Asheville, near Old Fort, and passes just west of Charlotte. For Native Americans one of the few safe passages across the Catawba was at Tuckaseegee Ford. The ford (a shallow crossing with a hard bottom) was at a point where the Tuckaseegee Trail, used by American Indians long before the arrival of Europeans, crossed the river. A few miles to the east the trail intersected another ancient trail, known as the Trading Path. Today, that intersection of the two ancient trails is Charlotte’s major intersection at Trade and Tryon. Would Charlotte, North Carolina’s “Queen City,” exist but for a Native American crossing, Tuckaseegee Ford, over the Catawba River?

Long before Europeans arrived in North Carolina and the South, rivers served as transportations corridors and food sources for Native Americans. The “V” in the lower middle of this picture, is an ancient Indian weir used for catching fish on the Mayo River in the Roanoke River Basin. Also note that this beautiful piedmont river is protected by a wide forest buffer!

Perhaps even more famous than Tuckaseegee Ford are Trading Ford and Shallow Ford, both on the Yadkin River near Salisbury. Like Tuckaseegee Ford, each had been used by Native Americans, and later as a migration route for German and Scotch-Irish settlers, who arrived in the mid-1700s and helped Salisbury to become one of North Carolina’s most economically and politically important cities. These two fords on the Yadkin were also strategically significant during important battles in the American Revolution and American Civil War.

As noted above, a clear pattern is shown relating to the formation and existence of cities and the rivers that supply their needs. It is true for cities of the world, across the United States, and in North Carolina. Simply stated, cities exist on the shoulders of a river.

Our Riverine History

Over the past fourteen years while writing a natural history series aired on UNC TV, Exploring North Carolina, I have been constantly reminded of our region’s riverine past, incorporating both slow-moving “blackwater” rivers in the coastal plain and fast-moving mountain streams on Appalachian slopes. Across this state and the South, especially along back roads, there are numerous street names, signs, and roads in which the words “ford,” “mill,” and “ferry” are incorporated—i.e., Lassiter Mill Historical Park, Shallowford Road, Jessup’s Mill Camping and Tubing, and Jones Ferry Road. Such references to the past underscore the everyday relationship and encounters that North Carolinians had with streams, creeks, and rivers before the advent of interstate highways. Unfortunately, the same references also underscore the disconnect with rivers and water that now exists.

In North Carolina and in the South, rivers near the coast served as early transportation corridors for people and commerce well into the early twentieth century. Streams, creeks, and rivers were also obstacles to be forded, floated, or crossed on a rickety bridge. These “obstacles” also powered mills that ground our grain, and later spun turbines to create hydroelectric power. Rivers gave us fish and recreational opportunities, and, for many, a place for spiritual cleansing. In my office there is a picture of my grandfather, a Baptist minister, baptizing a hearty soul in an unnamed creek perhaps twenty feet wide. Although such scenes were not uncommon, my grandfather took baptism to an extreme: except for the baptismal hole cut in the middle of the stream, the slow-moving creek was frozen! Suffice it to say, a couple of generations ago, water courses were an integral part of life.

Now in my seventies, I acknowledge that not all memories of my relationship with moving water in the South are idyllic. While crossing two-lane highway bridges in the 1950s and ’60s, I remember asking my father why sections of Piedmont rivers, including the Haw, Deep, Yadkin, and Catawba, sometimes ran red, blue, magenta, or yellow. He told me that the colors came from the dyes used by textile mills located upstream, and that dye-colors of the day were dumped directly into rivers. I also remember trash and the stench of waste in the French Broad where it flowed through Asheville, and the same indignities could be found in many other rivers in the mountain region. West of Asheville in the 1950s, I remember walking along the Pigeon River next to plumes of sticky, brown foam that clung to rocks and vegetation. The brown chemical mess came from the paper mill upstream in Canton. Anytime I asked the “why” question—Why is the river so dirty, or why does it stink?—my father would answer with the same resignation as countless other fathers across the South and nation: “There’s not much we can do about it. People have to have jobs.”

Through the first half of the twentieth century, the same streams that powered our economy and washed away our sins were frequently contaminated by human and animal waste, making the water a vector for waterborne diseases including cholera, typhoid, meningitis, and polio. I was one of the last children in my hometown of Thomasville, North Carolina, to contract polio in 1953, and I remember being asked by doctors at Baptist Hospital (in Winston Salem) if I had recently been in a pond or river. After several months in the hospital, I was one of the fortunate polio patients to emerge relatively unscathed. While celebrating that water is a life-giving force, I’m also acutely aware that it can be a double-edged sword.

Basins and Buffers

North Carolina and other states in the South have abundant and reliable water resources when compared to most regions of this nation and world. In North Carolina alone there are seventeen distinct river basins, each with more than 40 inches of annual rainfall. Each river basin includes one large river for which the basin is named—including the Neuse, Cape Fear, Catawba, Lumber, White Oak, Roanoke, Hiwassee, and Watauga basins—and numerous smaller streams, creeks, and rivers. This amount of average rainfall is all the more impressive when one realizes that the amount of moisture on earth does not change, and that less than 1 percent of all water on earth is accessible to human use. Even though North Carolina goes through occasional wet and dry cycles, we should have no complaints when compared to the southwestern United States, sub-Saharan Africa, or any other location.

All told there are an estimated 38,000 miles of freshwater streams, creeks, and rivers forming North Carolina’s “circulatory system.” Just like the veins and arteries in our body’s circulatory system, permanent freshwater streams and rivers both drain and nourish North Carolina’s landscape. And let’s not get hung up on the size, or precise definition, of a “river.” No one, to my knowledge, has ever determined precisely when a brook becomes a stream, a stream becomes a creek, or a creek becomes a river. I know of many “creeks” that are far larger than other bodies of water designated as “rivers.” Contentnea Creek and Crabtree Creek, both tributaries of the Neuse, are wider, deeper, and carry more volume than many North Carolina rivers.

To understand why North Carolina has seventeen river basins, you must first understand that this is a very old landscape where some rock formations in the northwestern part of the state are more than one billion years old. Over several hundred million years mega continents—including Rodinia and Pangaea—saw land masses collide and then pull apart. In the process mountains were created, while valleys and gorges were cut by some of the same rivers that still flow in North Carolina today. The New River, which starts near Blowing Rock and flows north through Virginia and West Virginia, is thought to be one of the oldest rivers on earth. Another river, the French Broad, which flows out of the mountains near Brevard, courses through Asheville, and then enters Tennessee, is also deemed to be one of the oldest rivers on the planet. Each of these ancient rivers rests on the crest of the Appalachian Range when both the mountains and the rivers were created.

The power of water to shape the landscape is shown here at Linville Falls at the upper and of Linville Gorge. The water in Tar Heel rivers shaped our past and is the key to quality of life in the future.

Not long ago many geologists believed that the Nile River was the oldest on earth followed by the New River and the French Broad. Today, however, there is some argument about ranking the planet’s oldest rivers. Suffice it to say, North Carolina’s New River and the French Broad are still deemed to be among the oldest, and many other Tar Heel rivers, with lifespans in the tens of millions of years, are also very old even by geologic standards. More in a moment about the importance of “old rivers.”

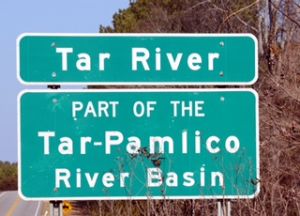

What does it mean when we say that North Carolina has seventeen river basins? And how do we define “river basin”? Over the years I have embraced three basic definitions of a river basin, which help explain their significance in our lives. The first definition is the topographical/geological definition. A river basin is the area encompassed by the principal river for which the basin is named and all of its tributaries—including other rivers, creeks, and streams. The river basin may also include sub-basins and watersheds. Water arriving at any point within the basin will be pulled by gravity and funneled downhill toward a single point at the low end of the river basin. River basins are separated topographically from adjacent river basins by geographic features including ridges, hills, or mountains forming a barrier. In the Piedmont and coastal plain, basin divides may be barely noticeable. Fortunately, on most major highways, the state of North Carolina has placed signs reminding us when we are entering or leaving a river basin. Citizens of every state should know not only their street address but also their “river basin address.”

Do you know your river basin address? Across North Carolina signs like this are strategically placed on the rivers and highways.

The second definition of a river basin draws from its political significance. Because water in a basin begins and ends within a fixed topographical/geological boundary, river basins are also planning units. Within basin planning units water is generally stored, treated, and released within the same basin. When a town or metropolitan region overlaps two or more river basins, planners must be concerned with interbasin transfers (the shifting of water resources from one basin to another).

The third, and, for me, the most significant definition of a river basin came from a fisheries biologist several years ago. Dr. Wayne Starnes works at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and is a specialist on Southeastern fish and their habitats. When I asked Dr. Starnes to explain the significance of river basins, his answer changed the way I look at them. He said: “In a very old landscape like we have in North Carolina, river basins must be considered crucibles of evolution.”

He went on to explain that many finfish species, salamanders, freshwater clams/mussels, and crayfish actually evolved in the rivers in which they are found. Some are endemic only to one or two river basins. For example, the Neuse River waterdog is a fairly large salamander species found only in the Neuse River and Tar-Pamlico River basins. Some Tar Heel species, such as freshwater bivalves (clams and mussels) and certain finfish, have even developed symbiotic relationships over thousands of years. Without the presence of certain finfish in a river, some freshwater shellfish species cannot reproduce.

North Carolina’s very old rivers have been called “crucibles of evolution.” Approximately 45 species of crayfish are found in North Carolina. In this clear mountain stream, see the crayfish in the center of this picture.

Starnes also reminded me that the fauna found in Tar Heel rivers is significantly different on each side of the Eastern Continental Divide. On the west side of the Eastern Continental divide in North Carolina, river basins—including the little Tennessee, the French Broad, Watauga, and the New—drain toward the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico. Rivers forming on the east side of the divide—including the Catawba, Yadkin, Broad River, and Roanoke—drain into the Atlantic. Even after centuries of human tampering with ecosystems, numerous fish, shellfish, and salamanders are still found only on one side of the continental divide. Distinct species may exist only a few miles apart, separated only by an ancient ridge created at the birth of the Appalachian range. The Eastern Continental Divide, and the smaller river basin divides on each side of the Appalachians, support evolution on a very old landscape.

Dr. Starnes’s terminology—“river basins as crucibles of evolution”—helped me to understand why North Carolina and other Southern states have such incredible biodiversity. In North Carolina alone there are approximately 265 species of freshwater fish, some 45 species of crayfish, 58 species of freshwater clams/mussels, and 60 species of salamanders (the most species of salamander found in any state). Other Southern states can proudly claim their own “homegrown” and endemic species, all of which are products of evolution.

Approximately 20 species of freshwater turtles can be found on North Carolina rivers and streams from the mountains to the coast.

I can’t let the opportunity pass without commenting on the delicious irony here. In this region of the country, where generations of religious and political leaders have made the fight against Darwinism and evolution part of our heritage, the evolution of countless species was taking place right under their noses . . . in our ancient Southern rivers.

The only sad footnote to the extreme biodiversity of the Southeast is that species have been lost to extinction or extirpation (removed from a state or region) over the last century. Every Southern state has a list of lost species, many of which are associated with rivers. They are gone because of the clearing of forests, the building of dams, or apathy. For example, in North Carolina’s Little Tennessee River Basin, several species of clams have been lost to extirpation and others are presumed extinct. Many scholars have responded to this loss of biodiversity, but no one more eloquently than E. O. Wilson, who is both a Harvard professor and a child of the Deep South. In his book, Biophilia, written in 1984, Wilson wrote: “The one process now going on that will take millions of years to correct is the loss of genetic and species diversity by the destruction of natural habitats. This is the folly our descendants are least likely to forgive us” (emphasis added).

No matter which of the preceding river basin definitions you prefer—(1) the topographical/geological definition, (2) the political definition, or (3) the biological definition—water quality can only be maintained when robust buffers are preserved. If we can recognize that we are carried on the “shoulders” of rivers and streams, great and small, then we must protect the living shoulders of these waterways. Stream buffers, also known as riparian buffers, hold riverbanks in place, act as filters/sponges to remove sediments, and provide shade and habitat for countless creatures. When buffers of 50 to 100 feet wide are maintained along larger rivers and streams, they are also very effective in removing excess nutrients and pollutants. Even along very small brooks and creeks, a ten-foot buffer can make an incredible difference in both water clarity and quality. Since North Carolina has no comprehensive or uniform buffer requirements, the importance of riparian buffers is diminished. As a general rule, the wider, the better, but all buffers are good!

Beautiful mountain stream like this one in Joyce Kilmer Forest are protected by large woody buffers. Forests serve as sponges and filters, and can help prevent flooding.

Even though I did not hear the term “riparian buffer” until I encountered it in law school, I understood the concept of buffers at a very early age. On a number of fishing trips with my father in the mountains as a preteen, I remember watching trout streams go from completely clear to a muddy torrent over a very short time following a thunderstorm. On other occasions I remember fishing in streams following a heavy rain and noticing that the water barely changed in color or volume. What was the difference?

When agricultural fields, timber operations, or residential yards are placed right next to a stream or river, without the benefit of a robust buffer, erosion will occur. Such incursions on the banks of a river can also cause a rapid rise in water volume and a diminution of water quality. The opposite happens where a stream or river runs through a forested area. A number of years ago I was allowed to visit the Asheville watershed surrounding the North Fork of the Swannanoa River. It is a magnificent 16,000-acre protected watershed encompassing the North Fork of the Swannanoa and its many smaller feeder streams. During my visit, a summer storm enveloped the area. After an hour of heavy rain the main river was still completely clear and had risen only a few inches. The mature canopy, the understory of smaller trees/shrubs, and countless ground-level plants had not only protected the soil, but had also acted as a sponge to prohibit the rapid run off of the heavy rain.

If you’ve ever wondered why riparian buffers protect rivers, look at the roots on this American beech tree. The roots of trees hold soil together and stop erosion.

Protecting our Rivers: An Inconvenient Burden

In 1972, with the advent of the Clean Water Act and supporting state regulatory legislation, water quality dramatically improved across the United States. Much of the “point-source pollution” from industry and municipalities was eliminated, as was “non-point source run-off” from agricultural lands and residential areas that carried fertilizers and pesticides into waterways. Because of these regulations, and the will to enforce them, my children have never seen rivers running red, green, and blue; have never seen plumes of sticky foam from paper plants; and have never smelled the stench of direct municipal sewage discharge into North Carolina rivers.

How soon we forget. Now, a new generation of political leadership wants to roll back legislation that has protected waterways for over a generation. Rivers and streams are now an inconvenient burden, too costly for government to protect. Equally significant, however, many citizens simply do not consider themselves attached to the rivers and streams that sustain our cities. For me the lesson is clear; each of must be part of the buffer, whether we live on hilly land in the mountains or Piedmont, or on flatter ground in the coastal plain. Buffers must begin in our yards and on our business properties. Whenever possible we should remove impervious driveways and walkways (ones that do not allow water to soak through). Every day we see paved driveways and patios in our neighborhoods and thousands of acres of paved parking lots in our cities. Why then, do we wonder why flooding occurs even after moderate rains?

Most of us are smart enough and courteous enough to treat friends who support us with great respect. Yet, for reasons that I cannot explain, we have little respect as a society for the streams and rivers that support our cities, provide power and recreation, and even “wash away our sins”—as with my grandfather’s congregation. We dam them, channelize them, and cut away protective vegetation on their shorelines. To add insult to injury, North Carolina political leaders even attempted to reduce the need for vegetated stream buffers with the use of “SolarBees” (solar-powered water circulation devices) in a recent experiment on Jordan Lake in the Haw River watershed. In all fairness to the manufacturer of the SolarBees, the devices were never intended to replace stream buffers, but were offered as a partial solution to circulate and oxygenate stagnant water. Even after the SolarBee experiment failed, some political leaders still seem hell-bent on eliminating buffers and “removing the heavy hand of government” from our waterways.

Buffers not “Bees”: Although technology, like the SolarBees tested in Jordan Lake, is important to maintaining clean water supplies, it will never take the place of riparian buffers which protect both water supplies and provide wildlife corridors.

Since we now speed over rivers on wide interstate highways and drink our water from plastic bottles with brand names such as Dasini, Aquafina, or Evian, it is easy to ignore rivers. Because chicken and pork prices are kept low, it is easy to ignore large-scale animal operations located perilously close to our rivers. When we shop in a big-box store and partake of many acres of parking on the banks of a river, it is easy to ignore the potential for runoff. When we pour that extra fertilizer and pesticide on our front yards just before the rain comes to wash it away, it is easy to ignore the river into which it flows. Because we will probably never see the endangered salamander or mussel located downstream, it is easy to ignore the river. Is this any way to treat a friend whose shoulders bear your burdens and protect your future?

*All photographs taken by the author

A wonderful story–interesting and informative. I was born and raised at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains, at the crossroads of the Coosa River and the Choccolocco Creek in rural Alabama. I can identify with the many changes of our rivers and waterways; the damaged by, in our case a large and powerful chemical plant, mills turning our waters indigo-blue and often the color of the rainbow…. sad that we lost the ability to play and feed from the clear rivers and creeks that I enjoyed in my youth. I am in my late 70’s and wish for these former areas…