Better Days in My Town

Meridian

The town that we all love

Meridian

The town that has the reputation

That no-body denies

It’s the place where

Joy is boss

You’re never cross . . .

We couldn’t fully fathom, it seems now, the place’s riches. The lovely tree-shaded rolling lanes lined with cottages and grander homes and gardens; the endless days of box hockey and kick-the-can and biking to every corner of town; the characters and the watchful old people; the electrifying fall nights in the lofty cement bleachers of Ray Stadium; the bustling downtown, where trains rumbled by relentlessly, friends and cousins lined up for Temple Theater movie shows, and the aging Threefoot Building—east Mississippi’s own skyscraper!—impressed without fail.

As my grandfather, a one-time vaudeville performer, conveyed in his adoring ditty, Meridian, Mississippi, was a town to be reckoned with. It had identity and a certain swagger.

But change was happening; the certain sense of promise was becoming uncertain. The shift was gradual, almost imperceptible to those of us who grew up there in the sixties, but Meridian’s glory days were on the fade.

We had taken much for granted.

For white children such as myself, products of professional-class parents, decent public schools, and stout churches, there was little reason to think that the ascent of Meridian, a city of some 45,000 at the time, wouldn’t continue without interruption. My very busy father, a lawyer who was elected district attorney, and mother, a theater director and speech instructor, seemed caught up in an irrepressible civic march of progress.

Nestled amid the hills and forests of a remote spur of the Appalachian Mountains, this Mississippi community claimed more than its share of industry and culture in the post–World War II years. It boasted a renowned community theater, an orchestra, a respected junior college and municipal airport, and even a state hospital for the mentally ill. Everyone closely followed the high school football team, the Wildcats, which perennially embarrassed the players fielded by lesser communities around the state. Football games at Ray Stadium, built many years earlier to seat 14,000, at a scale virtually unheard of for high school stadiums, approached the realm of religious experience. (As seconds ticked away during a goal line stand, the chant “GO Cats GO! GO Cats GO!” would rise up like an earthquake, shake the stout structure, and echo through surrounding neighborhoods.)

Ever since its gritty, rapid comeback from the destructive wrath of Union General William Sherman, who was famously credited with reporting, “Meridian no longer exists” after torching the strategic railroad crossroads in February 1864, my hometown has flirted with greatness. Jimmie Rodgers, the “singing brakeman” of the 1920s who shaped the development of country music, was from there. The sixteen-story Threefoot Building, an Art Deco masterpiece built in 1929 by Jewish-German immigrants, along with the older Weidmann’s Restaurant a few blocks away, gave Meridian special status as a center for trade and good times. It was at the city’s airport in 1935 that a pair of scrappy young flight enthusiasts, brothers Fred and Al Key, stayed aloft in a small plane called the Ole Miss for twenty-seven days (with the help of in-flight refueling and supply deliveries) to set a new flight record, in the process boosting Americans’ general confidence in aviation travel.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Meridian native Hartley Peavey built an audio equipment manufacturing company that would eventually become one of the world’s largest. The homegrown innovator and entrepreneur never realized dreams of becoming a rock star, but his amplifiers made rock ‘n’ roll history.

Meridian wasn’t a big place, but it was a place where big things could happen. Boosters dubbed it the “Queen City,” a reference to its rivalry with the capital city of Jackson, ninety miles to the west on Interstate 20. (By other accounts, the “Queen” moniker stemmed from the tantalizing fact that a famous Gypsy queen was buried in Meridian about a century ago.) When construction of the Meridian Naval Air Station (NAS) just north of town began in the late 1950s, roughly coinciding with my personal arrival at the old Riley Hospital, the military project reaffirmed the city’s reputation as a New South success story. The appearance on Meridian streets of young fighter jocks in their sporty convertibles, often accompanied by overexcited local girls, was another sign that Meridian was stepping onto a bigger American stage.

Proud sentiments filtered down to Meridian’s children; I vaguely recall field trips out to Meridian NAS to gain a glimpse of new-generation jets, and we learned about the Key brothers and assorted other local heroes. But we were far more concerned with the more ordinary details of life in a small Southern city: picking sandlot teams, catching fireflies in jars, making skateboards for rides down steep back streets, collecting and trading beer cans bearing obscure labels, playing all-night Monopoly games during sleepovers, going skinny-dipping if the opportunity presented itself (especially during the more sultry summer nights), making crafts and hearing stories about a most impressive young Jesus at Vacation Bible School. Meridian was the ideal setting for these things—and for growing up generally.

Even as our parents joined their contemporaries in propelling the growth of Meridian’s Jaycees (Junior Chamber of Commerce), they encouraged us to enjoy small things, to use our imaginations. One page from a circa 1960 scrapbook kept by my father preserves a Meridian Star clipping about the Jaycees development drive—as well as a note to the Tooth Fairy from my oldest sister. “Dear Fairy,” it says, “I’m sorry but I lost my tooth. I hope it’s ok. If I find it I’ll put it under my pillow.” Meridian was a fine place for the Tooth Fairy or for Halloween trick-or-treating.

My town served up exciting Little League seasons and, in spacious Highland Park, a wonderful old swimming pool and carousel; Highland dated to the early twentieth century, when it became one of America’s “streetcar pleasure parks.” I learned to swim in the city pool one summer, and spent memorable afternoons whirling around in the historic carousel house, engulfed in its tinny carnival music. Just around the corner was a snowball stand with all sorts of syrup flavors. Meridian also offered some of the more generous and talented public school teachers to grace the profession, people like Barbara Walker of the third grade at Poplar Springs Elementary, who brought in guest speakers, introduced us to classic children’s books (Charlotte’s Web comes to mind) and forgave our more embarrassing outbursts during show-and-tell.

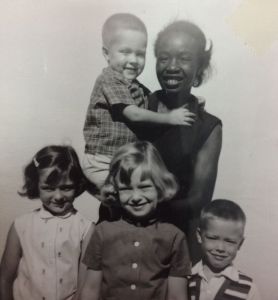

At the time, at very young ages, we had little awareness of racial injustice and the gathering storm of the civil rights movement. Meridian was as segregated as any southern town; there were no African American playmates. The “colored” and “white” water fountains in public places aroused mild curiosity, but what happened in or to black Meridian was mostly invisible to us. What we did have was Leila-May, a young black woman who served as housekeeper and, because of my parents’ many responsibilities (hectic careers, four children at the time), surrogate mother. Leila-May, who lived in a crowded, rundown shack on Meridian’s north side, filled a stereotypical role, and it speaks volumes that I never learned or felt obliged to use her last name. Still, she administered tender care and stern discipline, and the affection between us all was genuine. Her influence was such during one period that my brother and I, unconsciously picking up elements of her dialect, refined a hybrid language that only the two of us could understand. This was jarring to our parents, who promptly arranged a visit to a speech therapist.

Our personal adventures in Meridian reached well beyond secret languages. To be clear: in this kind of town, populated mostly with trustworthy people, parents didn’t keep close tabs on you. This freedom allowed room for all kinds of questionable behavior. We had firecracker wars with friends (“Get rid of it quick when you light it, so it doesn’t blow a finger off!”). Countless yards got rolled with toilet paper. No disrespect to Harper Lee’s fictional characters in To Kill a Mockingbird, but we had a neighborhood attraction ranking up there with the mysterious Boo Radley: a high schooler known as Sambo Mockbee, who lived in a spooky house across the street from ours, a creaky wood structure that had been a hunting lodge before the city grew up around it. Samuel Mockbee, who later became a famous architect in Jackson and at Auburn University, taught the neighborhood small fry how to play five-card poker and concocted terrifying tales about Mossback, a creature who crept around the fringes of a Boy Scout camp and picked the scouts off, one by one.

My older brother and I hadn’t forgotten about Mossback when we signed on with Boy Scout Troop No. 40, sponsored by our church, Popular Springs United Methodist. But there were more pressing concerns than ghost stories. Our troop had its good points, but also turned out to be one of the rowdiest in the Choctaw Area Council. Our games of tackle-the-man-with-the-ball were positively bone-crunching, and some of our wayward members enjoyed swooping through the camps of other troops during camporees to cut down their tents. I didn’t advance far through the Scout ranks and had mild envy for my brother, who earned Eagle Scout and even the honorary Order of the Arrow, qualifying him for participation in a Native American–inspired dance ritual next to a bonfire.

Our parents’ work lives and other pursuits expanded our horizons in all sorts of ways, for they were fairly public figures. Neither was from the east Mississippi town—my mother grew up in Tupelo, to the north, my father in the college town of Cleveland in the Delta. After they married and began having babies, they joined the young professionals who sensed opportunity in Meridian.

As an actress and theater director, my mother carved out a fine reputation at the Meridian Little Theater and at Meridian Junior College, where she also taught speech classes. She was attractive, enunciated beautifully, and made money on the side filming commercials for all sorts of local companies, often enlisting her four children in the homegrown ad spots; I can still recall my line from one commercial: “Dixiana Bacon—It’s goooood!”

Although slight in stature, Eloise Warner (Eloise Comer in her second marriage) cut quite an authoritative figure in the director’s chair. She could do the same at home, and on the occasions where meting out punishment was warranted, she leaned toward the dramatic. When I lifted a Baby Ruth bar from the grocery checkout line and she later discovered me enjoying the stolen candy, Mama hauled me right back to the store and had me deliver a fulsome confession to the manager. Crying impressed her not at all. When my brother was once reported huddling with junior high buddies to smoke cigarettes, a practice widely associated with the bowling alley hoods, my mother surprised us by not even raising her voice. Instead, she sat my brother down in the living room, handed him her pack of cigarettes and insisted that, since he was such a big man now, he could just smoke all of them, one right after another. This proved a lengthy and quite unpleasant exercise, and I doubt that he ever smoked again.

Drama of a different sort found its way to my lawyer father, especially after he was elected district attorney in the mid-1960s. Always drawn to politics, relishing the public eye, George Warner was determined to make an impact in his adopted community. We trailed him across his electoral district’s three counties, handing out “Let George Do It” fans and nail files at sweltering summer political rallies. After he won, my father settled into prosecuting a predictable mix of robbery, drug, gambling, and whorehouse cases, with an occasional bank robbery or murder. We were proud of how our own Perry Mason toiled in preparation for each trial and stalked the halls of the Lauderdale County Courthouse. What no one bargained for is that he would be swept up into Meridian’s significant chapter in the modern civil rights wars.

My father didn’t advocate for upending the racial status quo in 1960s Meridian, but he did believe in the rule of law. He despised the terrorist tactics of the resurging Ku Klux Klan, and as night riders began burning black churches and threatening Jewish leaders, he became an essential ally of Meridian police and FBI agents who were trying to bring the Klan to justice. The consequences of taking his oath of office seriously became clear enough one night when a commotion erupted in front of our modest 25th Avenue house and, peering through the curtains, we were perplexed and rattled at the sight of a burning cross. As it happened, that night my parents were out, and we absorbed the ritualistic warning in the company of a babysitter. When my father later learned of the cross-burning, he communicated a message through known members of the Klan network: If any of you venture to scare my children again, I will put aside the official prosecutor’s title and settle the matter personally.

The local struggle against the Klan and its sympathizers gained intensity in the summer of 1968 when a shadowy young hit man for the Kluckers, Thomas Tarrants of Mobile, began waging guerrilla war against local Jews who had spoken out loudly against the attacks on black churches. Adept at the use of dynamite and timing devices, Tarrants blew up the education building of Meridian’s synagogue, Temple Beth Israel, late one night and, eluding capture, returned to Meridian a month later with plans to blow up the home of a leading Jewish businessman. Meridian police had been tipped off about the second plan and were waiting in the bushes; a gun battle ensued, Tarrants’s female companion was killed, and Tarrants and a police officer suffered critical wounds. These events struck very close to home: the family of my best friend at the time attended Temple Beth Israel. In time, my father successfully prosecuted Tarrants on multiple counts of attempted murder. While he sought the death penalty, the Klan hit man was instead given a lengthy sentence to the state prison.

Within a few years, my father was voted out of office, denied a third term he felt he had earned. Perhaps he had made too many enemies as DA. But his role in helping restore order during a volatile time, when doing so could be quite hazardous, was remembered. In a letter to my father in December 1968, Police Chief C. L. Gunn expressed his “sincere thanks and appreciation for the hard work and the end results in the Tarrants case,” then added, “I believe that working together we can have a better city in which to live and raise our families.”

There was reason to think that things could, indeed, get better for Meridian. With the atmosphere of fear and violence subsiding, the community faced the myriad challenges of integrating its public schools. It was not easy, as I can recall from my first semester with a racially mixed seventh-grade class attending what had been an African American junior high. There were occasional fistfights and cultural divides to bridge. But the Meridian Public Schools still had tremendous assets; people from all walks of life still filed into Ray Stadium to watch the Wildcats play. Many of the city’s cultural institutions were holding their own, and coming years saw a wave of real estate development just to the south of the old downtown, as suburban-style malls became the rage.

But fundamentally, all was not well. Meridian followed a pattern familiar to so many small cities in the South and elsewhere: job centers shifted or disappeared altogether; people of means, most of them white, began decamping for the open spaces and more suburban schools out in the county, or enrolled their children in private schools. Most important, too many of Meridian’s bright young people moved away, never to return and provide the essential replenishment of civic energy. Meridian prepared to celebrate breaking the 50,000 mark in its municipal population, but instead the count began sliding backward.

At the age of thirteen, I left Meridian. My parents had divorced, and I, along with two siblings, joined my mother in moving to California after she married a navy pilot. (My father remarried, too, and picked up more children in the bargain.) As years passed and I returned to spend summers, landing a college reporting internship one summer at the Meridian Star, I noticed more signs of community atrophy. Downtown buildings that had once been so vibrant now looked sad as empty storefronts proliferated. Eventually the fabled Threefoot Building was shuttered and fenced off, its distinctive architectural touches prone to dislodging and shattering on the sidewalk. “For Sale” signs have sprouted along lanes where houses now suffer from neglect—the same houses that once were the picture of the American dream. I just don’t see the collective pride and sense of promise these days.

There are some hopeful signs. During a recent visit to see my father and other relatives, I was encouraged to read about the efforts of a Threefoot Building preservation society, and about one city councilman’s drive to combat housing blight. The restoration of a historic downtown opera house has revived a stunning live performance venue, just a short walk from the Amtrak train station. Meanwhile, a local branch of Mississippi State University is bringing new energy and investment, and I’ve heard of an effort to bring volunteers into the public schools to strengthen literacy teaching. Speaking for those who moved away from Meridian but in some ways never left, I dearly hope a new generation of leaders—in the spirit of the barnstorming Key brothers—will emerge and make good things happen again. Childhood memories offer useful reference points. This once remarkable town deserves a fate better than just muddling into the future, destined for irrelevance.

Bravo, Cole! You captured Meridian’s past and present and gave a boost to its future, and you did it with superior writing. Love the imagery you conjured up for me to see once again. The story of Meridian is too much like that of Greenville, Greenwood, Vicksburg, and many smaller towns of the Delta…they don’t seem to be doing too much, but Helena AR is getting with it.

Great work!

Wow. What a gifted writer you are, Cole, so proud to be your cousin. You truly captured the essence of Meridian and brought back many wonderful memories for me. I look forward to reading more from you.

Coleman, your talent and care for family memories is notable and so appreciated.

You have represented Meridian so well and you have blessed our family with your writings. You are loved so much and you are my wonderful brother. Thank you!!

Debbie

Outstanding piece. having only driven through Meridian, I nearly feel I lived there given the strength of prose and imagery. Let’s hope there is more to come from this gifted writer.

Cole,

Such sweet memories, now combined with reality of the past I did not know at te time, and the present which makes me sad, and hopeful for our hometown’s beautiful downtown. You captured it all!

With love from your former neighbor and babysitter,

Nancy Nicholson

This article says it all. I grew up in Meridian until divorce moved me to Shreveport and Houston for a few years. I always associated Meridian with the happest times of my life. The fifties and early sixties were the best. I finally moved back in time to graduate from my beloved Meridian High and stayed the rest of my life to this point. Now I want to leave and go elsewhere, maybe just move into the county away from all the mess that my city has become. When leaving the house and you grab your keys and your pocket pistol to go shop at the Mall or Walmart you know Meriidan is no longer Meridian.

A great story. I remember the same Meridian you do and miss the wonderful character it had when I was growing up.

And I have to say, I took a business law class from your dad at MJC.. I never enjoyed a class as much as I did that one.

You nailed it! You captured growing up in Meridian during the 60’s & 70’s perfectly. I moved away from Meridian years ago but it will always be in my heart & mind. Oh that Meridian would survive this draught & flourish once again!

i grew up in Meridian, from 1957 to 1972. I graduated from MHS in 1971. It was indeed a wonderful place to grow up. So many good memories. Since my mother’s death in 2002, I have made very few trips there. But I still hold fast to the wonderful memories. Thank you for sharing!

I’ve got connections to all that, being a Meridian boy.

“Weezie” Warner was my speech teacher and director in several plays at MJC (now (MCC).

I was dating and later married Lee Ann Hatcher, little sister of that seriously wounded cop at the Tarrants’ shoot-out, Mike Hatcher.

My mother was legal secretary for Gipson and Gipson, and later a Justice Court judge for Lauderdale County. She dealt with George Warner many times, when he as a lawyer and a judge.

My parents were part of that white flight from Meridian, settling at the all-white Dalewood community right after I left home.

Meridian will always be home, but she sure has changed.

A well-written article about my hometown. I remember my upbringing in Meridian, and can identify with much of what was shared. I would love to read more of your work.

Mr. Warner, Your article was a walk down memory lane. I was born in 1950 at Riley Hospital and claimed Meridian as my home for 36 years. As I read through your article, I would take my mind to the places, events and people you referred to. You reminded me how blessed my childhood was and how care free and safe I always felt. I love my hometown and wish it much prosperity. Thank you for this wonderful article. I like to think we are known as the “Queen City” because of the gypsy queen buried there. That always made Meridian so “mysterious” to me.

Respectfully,

Mrs. Nancy Harris Lucy

MHS Class of 1969

Great article bringing back great memories. I would argue that Troop 1 was better than 40 though, but maybe not as rowdy! 🙂 Chasing the fog machine was one of my memories of Meridian. Sambo’s dad taught us the Mr. Wizard card trick. A quick hello to your sister Debbie who I see posted above. I hope all is well with you Debbie. Everett Randall

Wonderful reading about Meridian! I grew up there until 10th grade then we moved to Phoenix AZ

My grandmother Ethel Harford lived right by Chief Gunn!

My other grandparents lived very close to Chalk school. We lived at 1303 48th Ave

Kind of close to the park and the field leading to the junior college.

Great childhood memories!

Thank you!

This is a wonderful writing that brings back fond

memories to many. Gene and I are stil

here. (married 65 years this summer.

I taught with Eloise at MCC(MJC) as well as enjoying

watching all of you (grow up). We see your

Father periodically.

Thanks for this memory. Your talent is appreciated.

Wilhelmine Damon

I lived on 40th street across from the nicholsons and next door to the Stacks. Read ing this has brought back many forgotten memories. I really believe those were the best of times. And I thank you!

An interesting and well done retrospective. And, as an expat Meridianite, I enjoyed the recounted memories. However, I couldn’t help but notice an extremely important omission: in June of 1964, civil rights workers: Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman were murdered(executed) by Meridian native, Alton Wayne Roberts. It pains me to admit it, but I knew Roberts fairly well because he and I both attended Meridian High School back then.

I loved this article, and also think you did a wonderful job. I came to Meridian in 1968, when I was 5 yrs old, due to my father being transferred to the Naval Air Station there. In 1969, I too remember the day we integrated the schools (I was a first grader) and we were bussed quite a distance to Middleton school. It was quite a tense day on both sides of the spectrum as I recall. Things did get better, as we moved to town and went to grade school at Witherton elem, junior high at Northwest, Harris high campus and Meridian High. It was sad to come and visit a few years back and see so many abandoned housed in our old neighborhood. Thanks for this great story.

Outstanding prose on a familiar topic. Meridian’s woes are blamed mostly on the shifted racial demographic from the past 20-30 years, if you listen to and believe north Meridianites. Regardless, it would be nice to see the town make a comeback and show some pluck and true relevance.

Thank you for bringing back the memories Coleman, we left in ’78.

Thanks Cole for a wonderful article. I grew up in Meridian during the times you described. I remember fondly the idyllic childhood–playing outside and roaming freely without fear. Miss Sadie’s playground was nirvana! Highland Park was Americana at its best. I remember also, the terrifying events of the Tarrants episode, and the integration of schools. Those were trying times but Meridian rose above them. Nowadays I live in Charleston, SC, but I still have precious family in Meridian. The stories I hear now about crime and violence in Meridian are both fear inducing and depressing. It’s sad to see such a beautiful city sliding downhill. I pray something can reverse the trend.

Although I too have wonderfully childlike memories of growing up there, some aspects you spoke of left me somewhat empty. I too remember and lived the Klan days and deviations , as many cross burnings and death threats toward my family and Dad. He is well respected and known for being a Civil Rights Attorney.

My youth was free, simple and down town was the place to be,all precious times. Sadly, our town will never be/have what nostalgia holds captive.

This is a wonderful writing and brings back many memories. I sent a comment the first time that I read this interesting message. I do not know whether it went through or not.

I taught with Eloise at MJC(MCC). We also loved watching all of you “grow up”.

Gene and I are still in Meridian-will have been married 65 years this summer.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. Come back when you can. We see your father

periodically.

Wilhelmine Damon

what an impressive writer you’ve become Cole. After almost 50 years you have revived memories long forgotten for me.

You’re old best buddy,

John Gilmer

I can relate to a lot of this. I remember walking to my dad’s place of work after getting out of school (Harris Campus)in the early 70s and getting hit by ice cream cones thrown by some different race girls who did’nt like me walking around them. I doubt you had that kind of experience. Certainly, it wasn’t as traumatic as the Cross Burning you saw.

I remember hot spots like the Lamp Post, Chicken Treat, Davis Grill, going to the post office on Sunday morning after church to see if my sister had a letter in the PO Box from her husband, stationed at that time in Pleiku, Vietnam. I remember what a big deal it was when the Sears store opened on 22nd avenue.

I met, through my father, a lot of guys who fought in World War two. We had some great men to look up to back then. I’ve seen so many of those men die of illness, some of it work related,and some die of loneliness after their spouse died before them.But few remain.

And the question at the root of your story is, WILL MERIDIAN SURVIVE? Will some person, as of yet unknown, rise up to pull all of us together to get our city back from the crime and rot? The corruption and the racism, unaddressed and virulent which ruins more than just our chances at a decent job,and leaves us with well to do and lower class divisions in both societies and mistrust between all corners.

I certainly hope Meridian gets such a person soon.I don’t care what color this person is.I know I’ve waited almost too long to do what some well advised people did when they were young, leave. And I am not wealthy enough to buy a place in the latest safe area.

Growing up in York, Ala in the 60’s and 70″s, Meridian was our “go to,” big city place. I miss the way it “use to be.” I took my daughter and grandkids to Highland Park for playing and swimming. Now I am scared to ride past the park. I truly wish that the leaders of Meridian could see past their on agenda’s, and support the Police Department in a big way, and change Meridian back to the great place it was. If change was brought on, by the leaders, I don’t think they would have to campaign to keep their positions! I think the citizens would just so very grateful…I know I would be.

Interesting look back on history and how we dealt with it, however most were good memories of the freedom we were blessed with. Remember guys riding bicycles miles to see girlfriends. Cole, believe your mom was the first “renaissance woman” I knew; was a freshman at the “W” when she decided to get her degree there, with four kids in tow! Thanks for a look back!

I deeply appreciate responses to my reflections on Meridian, especially the personal ones. I also hope that many more discover South Writ Large, an exciting addition to online journalism. Most important to me is the sentiment that Meridian is a special place that needs and deserves fresh leadership. Job creation (and retention), historic preservation (Threefoot Building, amazing houses), public school support, racial barriers, blight and civic identity all need far closer attention. Where’s the resolve?

Coleman, I remembered you were from meridian, but didn’t know who your dad was and so forth. A great read here as everything you’ve done always is. I have family there still.

Excellent Cole! You reminded and restored many precious & fond memories. Be blessed old friend.(\o/)

What a wonderful article and review of Meridian. Great honesty and insight. On our journey in the Marine Corps, in the early 70’s, my husband was stationed at NAS. We chose to live in the Meridian community and became members of Poplar Springs Dr. Methodist Church. I, also, became involved in the Meridian Jr. College drama departments performance of The Boyfriend. While at the church, I became the Youth Choir director and involved with the MYF. What a beautiful experience that was. I loved the Meridian community. I remember seeing a black church choir perform and became enthralled with their performance. We were from Arizona, and at that time, the Southwest Methodist Conference had a Black bishop. So, I, naively, suggested, at a staff/board mtg., that we invite the choir I had enjoyed to perform at our church. (Not realizing at the time all that had happened in the late 60’s in Meridian) Haha! I thought this choir would add energy and choreography to our worship service so that my youth choir could see what all of that energy involved as we moved into musical performances. Everyone at the meeting listened and nodded their heads and warmly allowed me to talk. They politely tabled the idea. Afterwards, one of the men who was a great supporter of mine, put his arm around me as we walked out and quietly, but not in a mean way, shared with me…”Barbara, you know why we have ushers at this church….it’s to keep the blacks out”. Needless to say, being in my early 20’s and from a western state who had not experienced any of these challenges, I could hardly speak. I did not ask questions, I could hardly speak. I just enjoyed the rest of my time in Meridian and loved those people who were so good to me….but, that comment has stayed with me for 43 yrs.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts and memories so artistically.

Love this article. Just visited this town for a memorial dedicated to my Uncle Larry Williamson who died at a 1970 helicopter crash at the base. I’ve been trying to find information on it. By chance would anyone here know anything?

In Loving Memory of Meridian, MS.. as it was. Enjoyed the childhood memories of the writer and shared comments of readers. I especially liked the smoking reference to the thugs at the bowling alley. FYI the thugs were allowed to smoke at Meridian High School as well. The School Days memories mentioned by the writer reminds me of School Annuals that people would “sign”. I remember a popular message many people would write “You’re great don’t ever change”, the City of Meridian did change. Who will rudder who will oar -bill scaggs

I seem to recall they had a designated smoking tree at the HS; appreciate your comments, all must pull together to make a future for Meridian. The MAX museum project is a good start,

Very well written article. I am not sure how long ago it was written but it definitely conjures up a clear image of what it must have been like to grow up in the south during that time period. I believe I may know you. I think we met at Woodleaf in the 1970s. If you are the same Cole you were an excellent writer back then as well.

Cyndi Alexander Rowden

Cyndi I sent a response by private email. Thanks.

As it happens, my partner lives in the house next door to where Alton Wayne Roberts lived after he was released from prison. A house on a lake just south of Meridian proper. It looks like Roberts widow died in 2018 and my partner did report seeing a very elderly woman with dyed jet black hair there, so perhaps it was her.

I lived with my partner at his place from 2017-2019 and the house that my partner lives in was originally owned by Paul Davis, a Meridian native with several hit songs (I Go Crazy, Cool Night, Sweet Life).

I had to leave Meridian though. There is just about zero things to do there and to have to drive 90 miles to a Whole Foods in Jackson (a tiny Whole Foods at that)is not where I want to be. Grocery Store choices – Winn Dixie and Walmart.

But more than that MS is so backwards and behind. My experience with the health care system in Meridian was jaw dropping. Not in a good way.

My partner and I are doing the long distance thing (I’m back in MI) and when he retires, we’ll move to a mutually agreeable place. Not Mississippi though.