Can Old Hickory Reclaim the South in 2016?

Consider what happened in the South this fall along the tortured path to the 2014 midterm election. Regardless of the political party or candidate they supported, Southern voters expressed a grave concern for the issues most dear to them while the candidates desperately struggled to respond satisfactorily to “the will of the people.” Lest the people’s will be taken for granted, the memory of recently ousted Virginia congressman Eric Cantor lay heavy on the minds of Southern politicos everywhere. Foolishly ignoring his constituents, the former House Majority Leader had become a Washington insider par excellence—always a dangerous position for incumbent politicians running for reelection in the South. The problems facing most candidates during this election cycle, however, extended well beyond their alleged associations with unsavory lobbyists and Capitol Hill cronies. Southern voters did not target flawed candidates nearly so much as they decried a seemingly broken system, thus submerging individual failures beneath a systemic deficiency of empathy and leadership—unless, of course, those failures and that deficiency stemmed from President Barack Obama. If we learned anything at all from the grueling midterm campaign, it is that the South laid bare its list of grievances against the Obama administration and, incredibly enough, voiced its own nomination for U.S. president fully two years ahead of time . . . a choice that may surprise some electoral observers neglectful of their antebellum Southern history.

Take a look at one instructive poll conducted by Elon University in early September 2014 (see http://www.elon.edu/e-web/elonpoll/091514.xhtml). The findings exemplify the major trends that animated voters throughout the South and, barring the unexpected, should continue to infuse Southern politics during the 2016 presidential race. According to the survey, a towering 71 percent of likely voters in North Carolina believed the nation to be headed down the wrong track, whereas only 38 percent approved of Obama’s job performance. These results indicate a profound, popular resentment toward the gloomy state of world and governmental affairs. Meanwhile, likely Tar Heel voters ranked international affairs/defense and the economy as the two most important issues facing the country (20 percent and 18 percent, respectively), while education, jobs, the government, and immigration registered well behind (to say nothing of poverty, religion, or the environment). If midterm voters in North Carolina roughly resembled their counterparts elsewhere in the South, and if the status quo essentially holds up for the next two years both at home and abroad—two big “ifs,” to be sure, but the available evidence points in this direction—then Southern voters at large will demand a new president with a highly predictable set of qualities. They will seek a political outsider representing a dramatic departure from the old administration; a democratic reformer promising to clean up Washington and defer to “the will of the people”; an economic populist willing to stand up for the average, working-class American; and a decisive leader with hawkish sensibilities in foreign as well as domestic affairs. By golly, whether they realize it or not, voters in the South have already made their selection for 2016: Andrew Jackson!

Fondly called “Old Hickory” by his contemporary admirers for appearing physically, mentally, and morally unshakable, Andrew Jackson is the only Southerner in U.S. history to have won the national (and Southern) popular vote for the presidency three times in a row—in 1824, 1828, and 1832. In each of his eventful presidential campaigns, the famous general from Tennessee embodied the characteristics most coveted by a restless and demoralized electorate, especially the white male population of the South. He was a celebrated military hero, of course, having crushed the British forces at New Orleans in 1815. Just as significantly, though, Jackson entered the national political arena in the early 1820s at exactly the right moment. Ever since the Panic of 1819, the young American republic had been reeling from one major crisis after another. The financial panic itself launched the first “great” depression in U.S. history, which lingered in some states—including North Carolina, Kentucky, and other hard-hit areas of the South—until the mid-1820s. Meanwhile, the first serious rupture in Congress over the western expansion of slavery had threatened to tear the Union apart, as politicians debated whether to give statehood to Missouri with or without a constitutional safeguard for enslaved human property. The eventual compromise in 1820–1821 preserved the peace but satisfied few Southern voters, for whom black chattel slavery was becoming ever more crucial from an economic standpoint. (Tellingly, only two-fifths of Southern congressmen who supported the Missouri Compromise won reelection in 1822.) Finally, by 1824, the whole political system looked increasingly corrupt and dysfunctional, as Thomas Jefferson’s great Democratic-Republican party—by then the only viable political party nationwide—splintered into rival factions of competing regional interests. Still doing business the old way, a handful of party members in Congress formed a traditional caucus and nominated the longtime Washington insider and Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford of Georgia for president. Aside from Crawford’s political allies within the party establishment, most Southerners, indeed most Americans, viewed these developments with disgust and sought a new leader unbeholden to what Senator Rufus King condemned as the “self-created central power” of the caucus system.

When Andrew Jackson ran for president in 1824, he positioned himself as a Washington outsider and democratic reformer offering a breath of fresh air from a government plainly out of favor among Southern voters. Although no public opinion polls exist for this period, the surviving evidence suggests that President James Monroe’s passive response to the Panic of 1819 severely dampened popular support for his administration, particularly his secretary of the Treasury. As the Southern candidate of “politics as usual” in 1824 (since Monroe would not run for a third term), William Crawford suffered both from his undemocratic nomination by “King Caucus” and from what fellow Cabinet member John C. Calhoun detected as “a general mass of disaffection to the Government” owing to the difficult economic times. Jackson, on the other hand, safely distanced himself from the “electioneering and intriguing” of his opponents in Washington, where “corruption [was] springing into existence, and fast flourishing” in the words of one partisan tract. Southern voters shared Old Hickory’s hostility toward the status quo, for he trounced Crawford in every state south of Virginia and Kentucky apart from Crawford’s native Georgia. Despite benefiting from the potent Crawford effect, however, Jackson went on to lose this controversial election to a Northerner and former president’s son, John Quincy Adams.

Only four years later, Jackson found himself running against another deeply unpopular presidential administration, one even more tainted by Southern perceptions of bad policy and alleged corruption. This time around, Old Hickory swept the electoral field of the South (except for Delaware and Maryland) in a crushing defeat of Adams. The Northerner Adams simply remained unpalatable to Southern voters still apprehensive in the aftermath of the Missouri crisis. Moreover, his expansive policy agenda for the federal government offended the sensibilities of states’ rights Southerners and followers of Jeffersonian principles. Worst of all, though, he and Secretary of State Henry Clay had made a “corrupt bargain” that secured the presidency for Adams—and the State Department for Clay—during the 1825 special election in the U.S. House of Representatives, after the original four candidates (Clay included) had failed to secure a majority in the electoral college. Accordingly, Jackson campaigned on a vague platform for democratic reform in 1828, just as he had in 1824, while focusing on one central issue: “Shall the government or the people rule?” In the South, as elsewhere, this message paid off handsomely for Old Hickory.

Drawing connections between the past and present is always a delicate project, best captured by Mark Twain’s apocryphal remark that “history never repeats itself but it rhymes.” Nonetheless, the political atmosphere below the Mason-Dixon Line nearly two hundred years later does look eerily similar in some key respects to that of Jackson’s day. In the months leading up to the 2014 midterm election, candidates from both parties shunned all associations with what Southerners generally perceive to be a failed presidential administration. Harkening back to the 1820s, a majority of Southern voters today blame the Obama administration—much like the former Monroe and Adams administrations—for the apparent dysfunction and corruption in Washington, recently highlighted by scandals at the IRS, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Secret Service. Southern perceptions of Obama himself mirror those of fellow Harvard graduate John Quincy Adams: elitist, out of touch, ineffectual, and unpredictable on issues like foreign affairs and civil rights. Above all, a widespread concern has persisted among many voters in the South, on full display throughout the late midterm campaign, that the Obama administration has been irresponsive to “the will of the people” since day one, more committed to what they consider unnecessary and even unconstitutional healthcare and environmental reforms than improving a sluggish economy. “I’m not Barack Obama,” declared Democratic senate candidate Alison Lundergan Grimes during her September television spot “Skeet Shooting”—right before burnishing her own credentials as a gun-toting, job-creating Kentuckian. Grimes subsequently stretched the anti-Obama position to extremes (among Democrats, anyway) by refusing to say whether she voted for the president in previous elections, as if a vote for Obama was vote against the people of the South. For their part, Republicans on the campaign trail constantly tied Democratic opponents to the “self-created central power” headquartered in the White House in their tireless efforts to generate a modern-day Crawford effect.

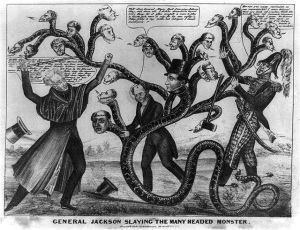

General Jackson slaying the many headed monster by by H.R. Robinson, 1836. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

If the Panic of 1819 launched Andrew Jackson’s rise to power on a surge of Southern populism, the Great Recession may produce parallel political results over the next two years. Despite recent disturbances overseas, the economy remains the number one priority for voters in the South, as demonstrated by the Elon University poll if we combine “economy” and “jobs” into a single category. Like the 1820s, the 2010s have witnessed a considerable improvement in prices, profits, and overall economic performance since the financial system crashed, yet many working-class citizens feel left behind as they compare their stagnant paychecks or continual lack of steady employment to the spectacular earnings exhibited on Wall Street. Eventually, Jackson transformed his vague promises of democratic reform in 1828 into an overtly populist economic message during his final presidential run in 1832. He had just vetoed a bill to recharter the allegedly corrupt Second Bank of United States so that the “humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers”—might also reap the fair rewards “of superior industry, economy, and virtue.” Similarly, Southern candidates on both sides of the aisle during the 2014 campaign pounced on a financial system that seems only “to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful,” as Jackson once described it. With an official unemployment rate of 6.2 percent (current as of September 2014), still somewhat above the national average, the South readily entertained Republican calls for middle-class job creation through government deregulation, faintly echoing Jackson’s war against the “monster bank.” Meanwhile, Democratic candidates emphasized equal pay for equal work and a higher federal minimum wage, thus expanding Jackson’s populist economic agenda beyond his wildest dreams without altering the core egalitarian message of his presidency.

As the Elon University poll clearly indicates, however, economic issues alone do not possess a monopoly over the political terrain of the modern-day South, nor did they in Jackson’s time. Regarding the thickly interrelated matters of foreign policy, immigration, suffrage, and race, the midterm election once again illustrates the powerful and complex legacy bestowed by Old Hickory to contemporary Southern politics. Jackson’s famed military career naturally made him the hawkish presidential candidate in the 1820s, but for Jackson, the use of armed force had always coincided with a greater mission of securing the liberty—and the property—of all white Americans at the expense of Native Americans and black people. Indeed, as general and president, Jackson systematically expelled Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the South and Southwest for the unambiguous purpose of enlarging the profitable slave labor regime of “King Cotton.” During the 2014 election cycle, Republican candidates in the South approximated this model of an exclusive, lily white democracy by linking illegal Mexican immigration with West African Ebola and the war against ISIS, while championing new voter restriction laws passed or proposed by Republican legislatures in numerous Southern states. Republican senate candidate Tom Cotton, for example, warned his listeners in a tele-town-hall meeting in October that “groups like the Islamic State collaborate with drug cartels in Mexico . . . [they] could infiltrate our defenseless border and attack us right here in places like Arkansas.” Democratic rivals countered this unique brand of xenophobic fearmongering—highly reminiscent of Jackson’s Indian removal policy and his Southern supporters’ paralyzing fears of slave rebellion—not only by assuming a more hawkish attitude toward immigration and foreign affairs but especially by employing the reemergent issue of minority voting rights to their political advantage. When prompted by MSNBC’s Chris Matthews with the statement “African Americans think that they’re being targeted [by voter restriction legislation] because they’re African Americans, not because they’re Democrats,” Senator Kay Hagan of North Carolina responded bluntly: “Well, you know, I tend to agree with them.” Along with current economic issues, therefore, Southern Democratic candidates such as Hagan offered an expansive but not irrelevant reinterpretation of the Jacksonian version of American democracy.

Throughout his political career, Andrew Jackson never ceased believing, as he once wrote to Vice President John C. Calhoun, “that [his] name will always be found on the side of the people.” Yet as history confirms again and again, popular conceptions of the “people” and their “will” have experienced spectacular fluctuations across time and space, the American South hardly being an exception. With the 2016 presidential election fast approaching, it behooves us to ponder which candidate, Democrat or Republican, might best replicate Jackson’s instinctual understanding of Southern voters and democratic politics in the South, even if the voters themselves and their political agendas appear quite different—or maybe not so much—from the boisterous days of Old Hickory. We now have some clues from the late midterm election, but still no definitive answers as to who will win the crucial states of the South in 2016, or how they will do so. Perhaps, one day many years from now, it will be said of the winning candidate, as it was said of Jackson, that he or she “was a friend of the people, battling for them against corruption and extravagance, and opposed only by dishonest politicians.” For better or worse, this robustly democratic conviction marks the great achievement of Andrew Jackson, one that he rode defiantly, by way of the South, all the way to the White House.

Selected References:

Sellers, Charles, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

Watson, Harry L, Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1990).

Wilentz, Sean, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005).

I expected Robert to enlighten me on my train ride home but was pleasantly surprised at the entertainment that went along with it. What a facility for making the sometimes dry and fusty history of Southern politics smack of today’s doings! Thank you, Robert, for making my commute glide by.

Robert, it is a rare scholar who can rise above the present to see the “repeats and rhymes” that weave and connect ideologies and actions throughout time.

Thanks for the insightful history lesson that explains what drives these complicated times.

I am glad that you make it clear that by “the people”, southerns still mean white people. In my view, until enough voters get over that all of the other fascinating and rhyming historical similarities pale in importance. The south votes differently than the rest of the nation, and has since Jackson’s day, out of the same assumption that the term “conservative” is a cultural given, and that is due to its bottom line clinging to concerns for race.