Four Wheels and a Box

I remember exactly when it started. Shortly before Christmas in 1984, my father pulled up to the house in a small, sporty Mazda 323. An unassuming car at best, with a rudimentary gearshift and no power steering, but it was brand new and my siblings and I fell hard: pure, unadulterated car love. For my parents, the Mazda was a half-hearted replacement for their first love. And this, as I reflect on it, is actually where the story begins.

My family roots in Alabama go back as far as anyone cares to remember and, on nights that involve the right mix of family and alcohol, that’s pretty damn far. My parents hail from central Alabama—Selma and Montgomery to be exact—and their courtship included many cross-country road trips orchestrated by my eccentric, bohemian grandmother as she insisted on hauling her six children back and forth across the United States and Canada every summer. I believe my grandmother was a creative type at heart. She managed to evolve her vocation as the mother of six into a tenure-track job as a professor of biology and eventually was promoted to head of her department. This, in Alabama of 1956, required creativity.

Family lore has it that one day she finished vacuuming and firmly announced she was done with household appliances, marched down to the college, and quickly landed a job. In my imagination, I love to run a cinematic version of that day with my grandmother played by Rita Hayworth. In that scene, she drops the vacuum with an affected look of both surprise and concern, suddenly aware that her life wasn’t exactly what she thought it would be. In one of those moments only screen sirens of the 1950s can pull off, she gets a brilliant idea about her next vocational move and exits her Montgomery home into the sunshine wearing a professional-looking trench coat, horn-rimmed glasses, and a sensible handbag.

But my feminine intuition tells me it wasn’t quite that easy, and like many women, her call to a more creative and self-directed life was filled with obstacles and detours. Unable to find or fuel the appropriate vehicle for her dreams, my grandmother did the next logical thing: She bought a station wagon. But instead of engaging in epic afternoons of carpool, she did something truly radical. She used the car to get away, taking her children with her. My grandfather, a quiet medical doctor we lovingly referred to as “Boss,” was unable to leave his practice for months at a time. This is where my own father enters the story.

My mother, the eldest of her six siblings, had been dating my father for a mere matter of months before my grandmother recruited him to help her drive six children on a summer-spanning adventure to the West Coast, north to Canada, and then back down through the heart of the country just in time to start a new school year. This was a process that she would repeat again and again, until the children were old enough for her to go back to work, at which point she transferred her wanderlust to foreign soil and began planning international trips for herself and her children to Europe, Central America, and the Middle East. She even found ways to incorporate her college students into her travel schemes, adding to her popularity as a professor.

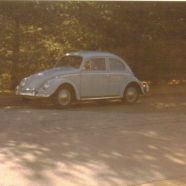

The romance between my parents survived the first epic road trip and blossomed into a marriage going on fifty years now. In the family spirit, they planned a honeymoon to Europe soon after they married. At the time the easiest and most cost-effective mode of transportation for their adventure was arguably the only positive contribution of National Socialism: The Volkswagen. In 1964, my parents picked up their Beetle in Paris and headed south through Italy, eventually parking it in the town of Brindisi on the eastern Italian coast to catch a ferry to Corfu. From Greece they traveled to Beirut and Jerusalem before heading back to Italy to pick up the car. They returned to Brindisi to find their beloved VW with a shattered window in the parking lot. The thieves didn’t get away with much more than a coat and some Italian gas coupons that were intended for tourists, causing only a slight hiccup when my father tried to explain their disappearance to police in his nonexistent Italian and thick Alabama accent. They worked it out, made their way back to France, and shipped the VW to the United States.

Our family drove that VW Bug until the floor fell out, literally, and it was with a heavy heart that my father eventually sold it to a collector who would give the car the love and attention it deserved. As kids, we embraced the doors that often stuck shut, and utilized both the sunroof and the windows during hours of play, doing our best impressions of the Duke cousins and Daisy, sliding in and out of the windows and sunroof hundreds of times over the years. We sat in the driver’s seat and imagined wild getaway scenarios down dusty country roads at high speeds. Looking back on those long days of play from my current vantage point, I realize something much more important was happening.

It was the dawning of a reality that even the smallest of spaces, if used properly, could spell release. Preferably these small spaces sat on four wheels and were powered by a killer V8 engine, but often more modest engines worked just fine. Now, as the mother of two small children, I somehow find myself back in the same terrain, as I slowly relearn the truth that even without horsepower, these tiny places can provide respite as long as your imagination stays intact. There have been many nights since my second child’s birth that the interior of my car seemed the only sane space in the world to me. Readily accessible, sometimes it provides the single sliver of personal space I can afford right now in the service of keeping my creativity alive.

It started out as a joke to a friend: Our 750-square-foot house was actually pushing 800 square feet if you included my car, which was slowly becoming my home office. I found this hilarious, mostly because it was true, but also because it underscored the reality of so many urban, working mothers that I know. The further I push into my thirties, the more I realize that the reality of even the most blissful domestic life precludes personal freedom at nearly every turn. I don’t mean this as a complaint. As an introvert, it’s a badge of honor. Learning how to build and nurture a family while keeping my wits about me in the small space we share is the greatest challenge of my life. And like my grandmother before me, I thank God every day for my car.

Unlike her, I’m not ready to strap my babies in the backseat and take off for California—at least not today—though road trips still sound enticing. Usually the fifteen minutes it takes me to drive my kids to school in the morning disabuses me of such fantasies, and I happily wave as I drop them off, wondering if at some point a general disgust with home appliances will press in so hard that I plan a trip from Austin to Niagara Falls, as my grandmother was wont to do, or pack up my brood and just head west. But I’m still four children short of her six, thank the Lord, so hopefully my sanity can hold just long enough that if I ever take my kids to Niagara Falls, it will be in the slightly larger compartment of a jumbo jet. In this month of May, as we celebrate our mothers and grandmothers and our own paltry attempts to raise small but decent human beings, I am grateful for the ways that confinement cracks us open. When all around us would suggest cracking up, we head to the places, though small, that release us. And in true Southern fashion we return, again and again.

I love this story for so many reasons, but particularly love hearing stories about the Coons I’ve never heard before. This proves there is a road trip gene, and you definitely got it. Would love to know what was playing on the radio on those trips to Canada 🙂

What A treat, Martha Lynn!!! We learned some new stories of your family!! We loved our road trips with 3 children and I can’t imagine 6 children and no Hal! Thank you for the tribute to mothers and grandmothers and to small,quite spaces for our sanity!! Keep writing as God has truly gifted you!!!

All our love and prayers to your growing family!!

Jean and Hal 🙂

Let’s rent a big bus and load it with lots of “goods”, and sing our way somewhere out there without destination.

Yeah, those floor boards rusted out. We had a piece of one by twelve over the back seat floor to keep us kids from putting a foot through the rust hole. Being down south, without the road salt, I’m not sure I would have expected you to have had the same experience. Curiously, our bug also came back on a boat from Europe but, ours must have been a 70s model, tomato orange convertible, similar fate. Shame I cannot cite the year.