Getting Away from it All

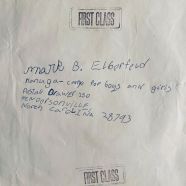

A giant handmade card found its way to me in June 1992. The envelope, saddled with extra postage, bears my name and the address of my summer camp in the scrawling cursive of my then eight-year-old brother:

Kanuga—Camp for Boys and Girls

Postal Drawer 250

Hendersonville, North Carolina 28793

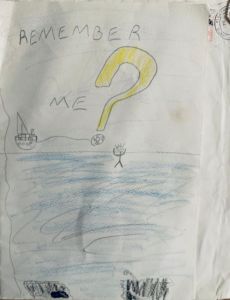

The front of the card bears the all-caps question, “REMEMBER ME?” followed by a huge yellow question mark that dominates the upper half of the page. The lower half shows a body of blue water with a boat hovering near the horizon. Someone stands on deck aboard the ship while another figure dangles precariously in the middle of the frame, frowning and unmoored. Upon closer inspection, I noticed that the dot of the question mark is actually a life ring, the tether of which is held by the figure on the deck of the boat; the ring is just beyond the reach of the frowning figure in the water.

The front of the card bears the all-caps question, “REMEMBER ME?” followed by a huge yellow question mark that dominates the upper half of the page. The lower half shows a body of blue water with a boat hovering near the horizon. Someone stands on deck aboard the ship while another figure dangles precariously in the middle of the frame, frowning and unmoored. Upon closer inspection, I noticed that the dot of the question mark is actually a life ring, the tether of which is held by the figure on the deck of the boat; the ring is just beyond the reach of the frowning figure in the water.

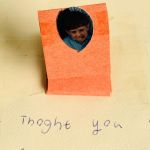

Upon opening the card, a construction paper spring jettisons forth a tiny photograph of the writer. Written below is the caption, “And you thought you were away from it all.”

As if I could forget my brother in the span of a few days away from home.

Looking back on my summers at camp—from ages eight to sixteen—I don’t think I ever considered camp as an escape from home or “real life.” Isn’t all life real, anyway? Going to Kanuga simply became part of my childhood and teenage existence, a routine marked each early summer by checking each item off the fairly predictable shopping list, ironing name tags into each new piece of summer clothing (including the wildly popular Jams shirts and shorts), packing everything neatly into a blue pressboard steamer trunk, and making my way as an unaccompanied minor aboard a Piedmont flight to Asheville, North Carolina, and then hopping a shuttle driven by a counselor a further hour to one of a handful of addresses I still remember completely, even down the zip code, to the spot in the heart of the Blue Ridge where my brother’s message found me almost three decades ago.

Now in my forties, I frequently recall those summers at camp—anywhere from ten days at first to a full month as I got older—as more formative than I’d ever realized. Other than a ten-minute bout of homesickness my first summer, I relished my newfound independence. Suddenly I was living among strangers as we negotiated our new communal space, quickly making friends with each other in the process. We cleaned our cabin daily with the singular goal of winning cabin inspection. I think the prize was extra candy at that day’s canteen: a double dose of Nerds for me. We hiked and camped together, careful not to touch the inside of the blue tarp during a rainstorm to avoid a deluge of condensation. We clung to our swim buddies during free swim and held each others’ hands high during “buddy check.” We took turns setting and clearing the dining table for each meal. Together we sang loudly and in unison for all the forest to hear the universally known ditty denigrating the food:

The food at Camp Kanuga, they say is really fine

A roll fell off the table, and killed a friend of mine

Oh, I don’t want no more Kanuga life

Gee mom I wanna go, but they won’t let me go,

Gee mom, I wanna go home.

As each camp session wore on, we got to know each others’ quirks, what music we liked, who we had crushes on, and whom we wanted to ask to dance. When R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know it” blared over the speakers during a Friday night dance in the pavilion overlooking the lake, everyone instantly began dancing and running frantically in a circle around the room, hands flailing above our heads, with absolutely no awareness of the “real world” outside these pine trees beside this lake. The world according to Michael Stipe’s lyrics may have been ending, but here we would continue to be, making this barefoot acclamation that we really do feel fine. We have gotten away from it all.

For a few days or weeks each year, this was our real world. We were learning real things, like how to make sassafras tea, how to identify poison ivy (and not to mistakenly brew tea from it), how to shoot an arrow and presumably hit our target. We learned to wake up to the clanging of the morning bell, get to morning devotion on time, follow a surprisingly rigid daily schedule, and get to evening devotion in time to close the day holding hands and singing, you guessed it, kumbaya.

We knew we’d progress numerically over the years from Cabin 7 to 8 to 9 and finally 10 and then to the coveted Foxhole, the distinguishing features of which were attached bathrooms and a secluded location nowhere near the younger boys. The Foxhole had a name, not a number. This was big time.

Somewhere in this line of progression as an older camper, I began to appreciate rest period, which fell somewhere between lunch and free swim. It was then that I read Richard Wright’s Black Boy on my bunk, part of my summer reading list for the upcoming fall. Also during rest period, I wrote not only the required two postcards home per session, but many other letters home and to friends, hoping that each day at mail call my counselor, holding a bundle of our cabin’s mail, would call my name. I later learned that my mother had prewritten postcards ready to go in the mail each day, and I’m sure I have those somewhere, too. My grandparents were all also great correspondents, and I still have many of those notes.

But there’s something about this card from my brother. I really don’t remember getting it, or what I thought at the time, although I imagine I laughed pretty hard when his tiny, mischievous grin popped into my face. It was only recently in going through boxes of untold piles of things in my mother’s basement that I found it again.

I noticed something else about the card that I had long forgotten and almost overlooked even now. On the inverse of the front is a simple pencil drawing, a close-up of the boat from the horizon line of the cover. The life buoy has been pulled back into place along the mast, its cord wound neatly into place. A rescue has apparently occurred. Below decks seen through a porthole is a grateful stick figure uttering the words, “thank you.” Another figure seen through an adjacent porthole seems to be listening, a smile his only facial attribute.

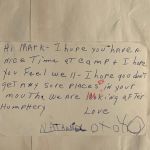

Also among these artifacts in my mother’s basement, I found another postcard my brother sent me at camp two years previously. Too young to write the text himself, he must have asked a babysitter to take dictation for a message he wrote concerning the status of my new retainer and the health of my pet gerbil. He writes:

I hope you have a nice time at camp and I hope you feel well—I hope you don’t get any sore places in your mouth. We are looking after Humphrey.

Love, Nathaniel OXOXO

His name and OXOXO are in his own hand and form a visual crescendo across the bottom of the postcard. I am so touched by his concern.

But I keep going back to the boat, the mysterious rescue mission, and the message of attempted—but not quite achieved—escape from home. The thwarted attempt at getting away from it all. Is my brother the one dangling in the water? Am I casting him the life buoy? Is he anticipating my arrival home as I pull him back into the normalcy of real life?

Or is he the one sending me a life line, ensuring that during rest period, as I settle into my bunk to read or write, that the counselor comes toward me with this huge envelope and calls my name?

All these years later, I’m not really sure who is rescuing whom.

Well, if you ever quit your day job, I am sure you could write some fantastic novels. I really have enjoyed reading this well-written piece & seeing another side of you, other than fun cousin whom I’m lucky enough to see in a summer scattered here & there.

Thanks, Olave!