Historic Black Travel: The Journey of Hershaw and Collins

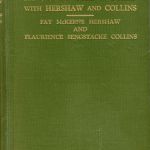

My interest in historic Black travel reached a fever pitch in August 2006 when I acquired an original, handwritten 1936 diary that served as the basis for Around the World with Hershaw and Collins, a 151-page account of the global travel of two educated Black women, published in 1938. During their four-month voyage, Fay M. Hershaw and Flaurience S. Collins traveled to Portugal, Africa, Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka), India, Japan, Nazi Germany, and Panama. They traveled on trains, planes, vessels, and other types of transportation available in these countries. During their travels, they were constantly amazed at how other white travelers mistook them for entertainers or musicians because, in these white travelers’ minds, it was impossible for Black women to travel solely for education or leisure.

- Around the World with Hershaw & Collins

- Sengstacke Collins Diary

My next task was to secure a first edition of this book and begin to study the differences between the diary entries and the book. I also wanted to learn more about these two Black women travelers and their backgrounds.

Fay McKeene Hershaw was the daughter of Lafayette M. Hershaw, a journalist, lawyer, strong supporter of W. E. B. Du Bois, and one of the organizers of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner to the NAACP. Fay received her education at the Columbia Teachers College in New York and lived in both Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. She was an educator in Baltimore’s renowned segregated school system for many years.

Flaurience Sengstacke Collins was the niece of Robert Sengstacke Abbott, the founding publisher of the Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s premier African American–owned and –operated newspapers, established in 1905. Flaurience was a graduate of Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee. She began working at her family’s newspaper in 1931 as a copy editor and worked in various roles until she retired in 1975.

When the book was published in 1938, the Washington Afro-American and the National Urban League’s magazine Opportunity, to name a few, did not give it favorable reviews. Opportunity called the work a “sketchy and naive account of the globe trottings of two colored women” with “fleeting impressions” of the countries they visited. However, the reviewer acknowledged that the authors did not set out to portray this book as anything other than what it was—the travel diary of two Black women who were eager to see the world.

While the book was criticized for giving a topical view of the countries, there are many fascinating tidbits to be gleaned from the entries. In mid-1936, Fay and Flaurience traveled to Nazi Germany, where a branch of Flaurience’s mixed-race African and German family lived. She was horrified to learn that the family had been removed from school, fired from their jobs, and deprived of their basic rights. Any portraits of their African ancestors had been removed, and they asked Flaurience to no longer send copies of the Chicago Defender because it published unfavorable reviews of the Third Reich.

More than eighty-five years later, it would be fascinating to retrace the steps of Hershaw and Collins and visit the sites they saw back in 1936—to see what is still left and what has been demolished; to observe the cultural mores and traditions that have been erased; to compare the finances of the trip then versus now; and to feel the excitement these two Black women felt as they experienced life beyond America’s strict Jim Crow boundaries.

This narrative continues to inspire young Black women decades later. In 2020, students from the Global Black Feminism class at Stanford University studied archival materials related to underrepresented Black women. One sophomore student studied Around the World with Hershaw and Collins and was surprised to learn that Black women had the means to travel in the early 1900s.

The spirit of Hershaw and Collins’s journey is best summed up in a quote by author, poet, and godmother of Black travel Maya Angelou: “Human beings are more alike than unalike, and what is true anywhere is true everywhere, yet I encourage travel to as many destinations as possible for the sake of education as well as pleasure.”

In the seventeen years since I first discovered Hershaw and Collins’s story, I’ve created a category in my collection of Black Americana artifacts dedicated to historic Black travel. This includes passports, letters, photographs, scrapbooks, diaries, newspaper clippings, airplane receipts, court cases dealing with 1880s segregated interstate travel, and much more. I even found my 1975 report about my trip to England as a teenager that first opened my eyes to international travel. This collection highlights how despite social, cultural, and often economic limitations, Black people were able to explore the world and document their journeys.