Interview with Lisa Alther

What initially inspired you to write about the Hatfields and McCoys?

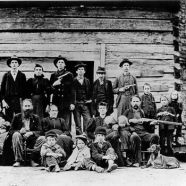

My editor asked me to write the Hatfield–McCoy book, maintaining that a history for a general readership hadn’t been written in thirty years. As I researched the topic, I discovered new information about the role of the feudists in the Civil War, and also two new volumes of Hatfield family reminiscences that hadn’t been included in previous books. In addition, I realized that no one had written about the bystanders—the women and children, the peace-loving neighbors, those who moved away to escape the violence, the future generations. I wanted to explore the far-reaching ramifications of the feud. But I especially wanted to examine the causes of the feud—and of violence, in general. I wanted to figure out why the region in which I had grown up seemed to marinate in violence, more so than other places in which I’ve lived since.

What did you find in your research for Blood Feud that was expected?

I expected to find a lot of senseless bloodshed, and I did. I also expected the violence to stem from the theft of a hog, which was only partially true.

What did you find that was unexpected or surprising?

I encountered a lot of surprises. For instance, I was surprised to discover the origins of the feud in Civil War clashes among guerrillas, home guards, soldiers, and deserters from both sides. Many were living off the land, raiding the supplies of civilians, and burning down the houses and outbuildings of their enemies. I had never fully realized what a terrible time civilians in the border states experienced.

I was also surprised to learn about the role of Perry Cline. His father died when he was nine, leaving him 5,000 acres of timberland. When he tried to log it, his closest neighbor, Devil Anse Hatfield, accused him of straying across their boundary and launched a court case against him. Cline fled, forfeiting his land to Hatfield. In a later letter he indicated that some kind of intimidation had been involved. He emerged as an important leader in the McCoy pursuit of the Hatfields during the final years of the feud.

I was also surprised by the large number of other feuds that took place in Kentucky at the same time, several running much longer and involving many more deaths than the Hatfield–McCoy feud.

I was further surprised to discover that several of my distant ancestors had been on the fringes of feud events and probably knew some of the feudists. A distant cousin was murdered by Jim Vance, Devil Anse Hatfield’s uncle, after Vance murdered Harmon McCoy in an opening salvo of the feud. I hadn’t realized that my family is related by marriage to the Hatfields, as well as to the McCoys. Our branch of the McCoys moved away from the feud area to escape the violence, moving back after the feud ended.

What originally inspired you to write Washed in the Blood? What were the similarities and differences between the story of the Hatfields and McCoys and the story of the characters in Washed in the Blood?

I met a cousin who claimed that our shared ancestors were Melungeons. This launched me on a quest to discover who the Melungeons were, where they came from, and whether or not my ancestors had been among them. After ten years of research, I wrote Washed in the Blood to organize my thoughts. I didn’t use the term Melungeon in that book because I had come to believe that the Melungeons were just the tip of the iceberg of this process of racial mixing that had occurred throughout the eastern third of what became the United States in the earliest years of exploration and settlement.

Blood Feud is a narrative history in which I tried to deal as closely as possible with facts. Washed in the Blood is also as factual as I could make it, but the facts were few and far between, especially for the section set in the sixteenth century. Blood Feud concerns actual people, but my characters in Washed in the Blood are imaginary, although loosely based on ancestors of mine.

Initially, I thought that family would determine allegiances during the feud, but I soon discovered that lines of loyalty were very blurred. Hatfields and McCoys fought on both sides during the Civil War. Many Hatfields and McCoys had intermarried over the generations, and some feudists were related to both families. Devil Anse Hatfield’s oldest son romanced Ranel McCoy’s fifth daughter and then married the daughter of Harmon McCoy, whom Devil Anse’s uncle had murdered. Some McCoys with economic ties to the Hatfields fought for them in the feud. Some Kentucky Hatfields testified in support of the McCoys during the trials that ended the feud.

The stereotype of a clearly drawn line in the sand between the two feuding families turned out not to be true. Likewise, the characters in Washed in the Blood were racially mixed, and some crossed back and forth over the boundaries that supposedly separated the races, regardless of the prevailing stereotypes about racial purity and exclusivity in the South.

What did you find out about racial and ethnic backgrounds in this part of the Appalachian South that came as a real surprise to you? How was the actual situation different from modern-day stereotypes of race in the South during that time period?

Because of my research, which included some DNA testing, I came to believe that many of the families who had lived in our region for eight or ten generations were a mixture of European (of various stripes), African, and Native American. I came to realize that the European and African explorers, long-distance fishermen, fur traders, soldiers, servants, and early settlers were mostly young men, who mated with whatever women were available, Native women in most cases, leaving in their wakes pockets of racially mixed children. I began to understand that there was no one origin tale for all Melungeons. Each extended family had its own story about how its early ancestors had arrived at the Atlantic coast of North America and what ethnicities they picked up as they pressed inland. But many of these people with darker complexions ended up clustering together and finding refuge on land that European settlers didn’t want—swamps and ridgetops. They kept to themselves and were stigmatized by the surrounding communities as having African heritage, whatever their actual heritages may have been. A man named Brewton Berry has written a book called Almost White, in which he discusses some two hundred such groups all over the eastern United States.

They say the victors write history, and in the Southeast during the colonial era, the British were the victors, triumphing over the French and the Spaniards and gradually erasing any record of their roles in the early settlement process. Once slavery became established there in the seventeenth century, it was dangerous to have ancestry other than northern European because a darker complexion could expose you to seizure and sale as a slave. And in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most “white” Southerners wanted to claim British descent because of the social and economic advantages that status bestowed. Many Appalachian families did have some British ancestry, so they continued the process of editing their family histories to exclude any non-British elements. The lines between the races grew ever more rigid, and families buried any lingering memories of nonwhite ancestors. African Americans have long acknowledged Native American and European ancestry, but “white” Southerners are just now starting to participate in an equivalent disinterment of their nonwhite ancestors, a process that could eventually deconstruct all the old assumptions about the exclusivity of the races in the South.

How do you think the research for these two books changed you as an author and as a person?

These discoveries have been exhilarating for me. Our family always harbored rumors of Native American ancestry. DNA testing suggests that these rumors are true. It also suggests some African ancestry, though the testing isn’t yet sophisticated enough to indicate how recent this may be. In other words, all European people have small amounts of African ancestry because that’s where our earliest human ancestors came from. But I don’t know yet if our family also has African ancestry acquired in North America, though I do think it’s likely. A couple of my male cousins who look “white” and believed themselves to be of European heritage have African Y chromosomes, probably from slave or free black ancestors.

There’s an incredible sense of relief that goes with unearthing buried truths. It’s almost as though your remote ancestors are crying out to you to be acknowledged. I feel much more at peace with myself than ever before, knowing that there is a basis in reality for my inability ever to identify completely with any one race, culture, or creed.

As an author, I’m really grateful to have such intriguing material to investigate. Most of what I’ve written throughout my career has involved trying to uncover the reality behind our cultural stereotypes. Certainly this stereotype of most Southern families as being either all white or all black is one that begs to be dismantled. Psychotherapy is based on the belief that bringing what has been unconscious into consciousness results in increased mental health, so I think and hope that’s the direction in which the South is headed.

Do you think you have been inspired by the “Southern gothic” literary tradition?

I think it would be almost impossible for a Southern writer not to be inspired to some extent by the Southern gothic tradition. I read Southern fiction avidly as I was struggling to become a writer myself, and I’m sure I picked up attitudes and techniques from all those wonderful Southern writers.

Who are your favorite Southern writers and what do you love about their writing?

I especially loved McCullers, Welty, O’Conner, and Porter when I was young. They showed me that it was possible for women to write amazing fiction, and that fiction didn’t always have to concern itself with going to war, or into the wilderness, or to sea in ships to hunt for white whales.

Where do you see the American South in the world and the wider world in the American South?

The South is an especially interesting region of the United States because it’s the only one to have experienced invasion and defeat in a war and the only one to have based its economy on slavery. This tragic history gives us a more realistic view of life, death, evil, and human limitation. In that sense I’d say our attitudes are closer to being European than are those of other Americans. Of course, the intense emphasis on a fundamentalist religiosity in the South also makes us more similar to the Muslim world than other parts of the United States. So I would say that our history and our psyches set us apart from the rest of the country—and make us quite intriguing to outsiders. But as the years go by, the myths of the plantation South are gradually decomposing, making the region more attractive to outsiders as a place to live. These outsiders are bringing their own tastes and cultures to the South and are enriching Southern culture through the inevitable process of cross-pollination—a process that has of course been in operation ever since Europeans and Africans first encountered Native Americans in the earliest years of exploration.

These two books, one fiction and the other non-fiction, provide insight into the struggles that were ever present in the lives of so many people in the rural South. They worked the land to provide food and shelter for their families, while often hiding their heritage to maintain their freedom to do so. I recommend both books.

These books help us all understand our common humanity and appreciate the precious diversity still evidenced in our relatives and friends. Lisa Alther tells enticing stories that draw us in and help us realize we are truly kin.

Arrena Hatfield Jones, Anse” Hatfields niece looks 100% Cherokee, she married John McSwain Jones who gave the land Nashville, Tn. was built on.

My great grandmother was Fannie Jane Hatfield. My grandmother was Volcent Smith, daughter of Fannie Jane and John Smith. I am blind with a rare form of a retina disease. I want to find other Hatfield family to learn if anyone else is blind with the same disease. I am also trying to find out if we have Indian blood. We were always told there was Cherokee blood in the Hatfield line. My grandmother was very dark and had Indian features.

There is Cherokee on the Hatfields line. My grandfather was Clayton Hatfield and he was told his mother was either full Cherokee or half Cherokee. Her name was Lucinda.

Do you know if Arrena Hatfield Jones was actually adopted? Lots of history pages online I only saw one that said she may have been adopted. She was Cherokee. Thx