Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss

Excerpts from Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss by Margaret Renkl

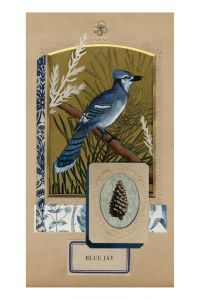

Jaybird, Home

Lower Alabama, 1968

Two weeks before my seventh birthday, my family left the sandy red dirt of the wiregrass region of Lower Alabama and moved to Birmingham, a roiling city built in the shadow of Red Mountain in the southern Appalachians. The move should have been a shock—I was leaving a town untouched by open conflict for a city notorious for its racist convulsions of water cannons and police dogs and church bombings—but I was six. I knew nothing of that. I missed the pine trees.

We returned to Lower Alabama often because my grandparents still lived there, in the house where my grandfather was born, and our long family history and frequent visits might explain why I imprinted on that landscape so wholly. Or perhaps it was the open windows, a time when what happened outside the house was felt indoors, or the innocence that sent children outside to play after breakfast, not to return till hunger drove them home again. I am a creature of piney woods and folded terrain, of birdsong and running creeks and a thousand shades of green, of forgiving soil that yields with each footfall. That hot land is a part of me, as fundamental to my shaping as a family member, and I would have remembered its precise features with an ache of homesickness even if I had never seen it again.

It would take all the words in Remembrance of Things Past to catalog what I remember about the place where I was born, but there are three things that can bring it all back to me in startling detail: the sight of a red dirt road, the smell of pine needles, and the sound of a blue jay’s call. And of those three, by far the most powerful is the call of the jaybird.

I love the blue jay’s warning call, the jeer-jeer, jeer-jeer it makes when a hawk is near. I love the softer wheedle wheedle wheedle and please please song for its mate. Blue jays have an immense range of vocalizations—whirring and clicking and churring and whistling and whining and something you’d swear was a whisper—but the sound they make that takes me right back to 1968 is a call that mimics a squeaky screen-door hinge. I hear that sound coming from the top of a pine tree, and instantly I am in the wiregrass region of Lower Alabama, where the soil is red sand, and pine needles make a scented bower fit for all my imagined homes.

Creek Walk

Birmingham, 1969

The rocks are gray slate, massive slabs cantilevered over the water as though the outstretched feathers of a great prehistoric bird had been caught in stone. My brother and I are barefoot, picking our way across the rock. We are always barefoot. The pads of our feet are thick, toughened by concrete and asphalt and gravel roads, and anyway shoes would be useless on this slick rock. Worse than useless.

We have not discussed a plan, and so we are making our way to the creek bed with no real intention. We have nowhere to be and nothing to do for hours on end, for days and days on end. It is summer, and autumn is inconceivable to us. School will be reinvented every year, an astonishment every year. Where were the nuns all hiding while we were walking barefoot on the hot concrete?

We are not thinking of school or of the nuns. We are thinking of nothing, or perhaps we are wondering if we will see another rattlesnake. Seeing any snake would be a cause for remark, but we have only once seen a rattlesnake. Mainly we will turn over rocks on the bank of the creek, looking for worms and roly-polies. We aren’t fishing—no one has ever taken us fishing; we are not the kind of children who would enjoy fishing—but we know we can summon fish by tossing worms into the water, and we like to feel the fish mouthing the freckles on our legs.

Sometimes there are salamanders on the bank. Sometimes there are tadpoles in the foamy water at the edges of the backwash. Sometimes there are crawdads under the rocks that jut into the water. Always there are dragonflies—blue, and bottle green, and scarlet red—hovering over the flashing water. Always there are jays scolding from the dark pines. We see them and we don’t see them, we hear them and we never register their sound. The mud and the moving water smell vaguely of decay, but the smell does not disturb us or inspire the first curiosity. We have never even noted it. These are our sights and our sounds and our smells, as casual to us as the smell of our own breath in our cupped hands, as the sound of our own blood in our ears when we lie down on the biggest rock and hang our heads over the edge to dangle tickletails in the water, tricking the fish into rising.

Farther down, closer to the highway, there are words scratched into the slate on the other bank. The letters are large and ghostly white: F U C K. My brother sounds it out, a perfect practice word for someone still learning phonics from the adventures of David and Ann, the Catholic school equivalent of Dick and Jane. “Fuck,” he pronounces, correctly. Then: “What does it mean?”

“It’s a word people say when they’re mad,” I tell him.

I don’t know what it means.

We pick our way back toward the bank we will climb to start heading home. Clouds of minnows race from our feet. Clouds of grasshoppers rise from the timothy grass above the rocks. Clouds of gnats hover above the water, part for our small bodies, and coalesce again behind us. We climb out and sit together on the slanted rock to wait for our feet to dry in the hot sun. At home it is almost time for supper, but we can’t tell time.

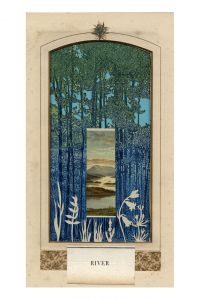

River Light

I try to imagine what it must have been like for the first human beings who moved through this dark forest: to glimpse a flare of light on moving water, to step out of the shadows of the close trees and see the sun flashing on a broad river. To see air and water and light conjoined in a magnificent blaze. That first instant must have felt the way waking into darkness feels—not knowing at first if your eyes are open or closed.

In that instant, the river is not a life-giving source of water and fish and passage. In that instant, it is not the roiling fury that can swallow whole any land-walking, air-breathing creature. It is only itself, unlike any other thing. It was here long before we were here, and it will be here after we are gone. It will erase all trace of us—without malice, without even recognition. And when we are gone to ground and all our structures have crumbled back to dust, the river will become again just the place where light and water and sky find each other among the trees.

From Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss by Margaret Renkl (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Margaret Renkl. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions. milkweed.org