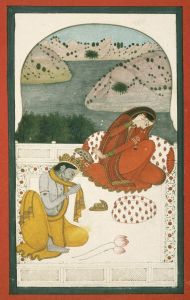

Khandita Nāyikā (quarreling with her lover), unknown painter (c. 1800). Detail. Brooklyn Museum, A. Augustus Healy Fund and Frank L. Babbott Fund.

Share This

Print This

Email This

Love, Beauty, and Poetry

We love what is beautiful. True love is more than the desire to possess, it is something that uplifts. One recognizes it without knowing where it springs from. In Pablo Neruda’s words: “I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where. . . . I love you as one loves certain obscure things, secretly, between the shadow and the soul.” And to be able to love, one must love oneself.

But familiarity makes words—and images—lose their power. In our age of information, the old literature not only is fingertips away in its original form but also in its many transformations and veilings by other artists. It is a challenge to go beyond time-worn metaphors and similes; lines that might have sounded fresh once now look stale.

According to Indian aesthetic theory of Bharata (second century BCE or thereabouts), there are eight rasas (essences) in any aesthetic experience: shringāra (love and erotic), hāsya (mirth, comedy), raudra (fury), kāruṇya (compassion), bībhatsa (disgust), bhayānaka (horror), vīra (heroism), and adbhuta (wonder). Later theorists added śānta (peace) to make it a total of nine. The challenge for the artist is to evoke them through the composition.

Love poems are suffused with shringāra rasa in one of two modes: union (sambhoga) and separation (vipralambha), and, of course, they can be joined with other rasas. If love is about the impending sense of loss, it is bound up with deepest emotions related to being. I joined a few of these rasas in a poem just a couple of months ago:

To live one must die everyday

To live

one must die every day

and not even make a sound

or sigh.

Read the notes

run the errands

answer email

and keep up

with stories of the day.

Walk with a smile

easy stride

make small talk

and before lights fade

say goodbye.

And when you find

a quiet corner

and no one’s watching

let the tears flow

and softly cry.

Love is about moments that are gone and that makes it paradoxical for memory is ever changing. Here’s a poem on time:

This moment

This moment

we remain imprisoned

in memories

that have seeped over

into the one moment

we have for each other.

Unable to separate the streams

we can’t tell

the difference

between what was

and what is

quickly receding

from the present.

The moment is like

the butterfly

that flies away

from the fingers

as we reach

to catch it.

This moment

will decide

what it means for us

as it oozes into

other moments.

As a child growing up in Kashmir with many languages and in an atmosphere of poetry and song, it is not surprising that I became interested in the essence of the poem, beyond the arrangement and choice of words. If that essence is beauty, we know how to recognize it, although it is not so easy to describe. Some say beauty is symmetry and proportion, but that couldn’t be the whole truth since cleverly broken symmetry itself is beautiful. There is a Sanskrit saying that what is beautiful appears fresh at each glance.

Another way of looking at beauty is that it must involve heart and mind. The spirit dwells in the matrix of the senses but does so like a bird in an outworn cage. The recognition of beauty is accompanied by heartache arising from pain and a sense of incompletion, which is the human condition.

Great art has universal appeal for it connects with the transcendent aspect of the self. It brings to us the mystery and the awe of our physical presence, its transience, and its persistence in a larger sense. The intimations of the beauty of Nature are in the dhvani (resonance) of soft whisperings.

But what about things created by humans? Music, painting, architecture, and dance have elements related to conventions so sometimes it takes learning to appreciate what has been created in another culture. Reflection also reveals that science itself has aspects similar to art. If most science is about description, it must also synthesize descriptions to obtain a sense of the overarching architecture. This conception depends on the mind and it reflects a beauty of one’s own nature.

The difference between the mind and consciousness is rather subtle. The mind is usually understood as cognitions associated with judgment, language, and memory, which are mutually intertwined, and underpinned by ego, whereas consciousness is pure awareness that is not colored by prior experience or emotional attachment. In Indian thought, consciousness is unitary (and called Shiva) and it illuminates the mind, just like light makes the contents of a room visible. Shiva is famous for his allegorical dance that signifies the fact that our perceived impressions and emotions are fleeting in their rise and disappearance.

Love is a feeling associated with the mind and there is this story where the god of love (Kāmadeva in Sanskrit, who is like Eros of Greek mythology) is destroyed by a glance of Shiva, which points to the paradoxical nature of love, and how attainment of the object of love can leave one with despair and emptiness.

Love and Rasa

The Gāhā Sattasaī (Sanskrit: Gāthā Saptaśatī) is an ancient collection of seven hundred poems in the Maharashtri Prakrit language, which is dated to first century CE and attributed to a king named Hāla. The poems are about love and separation and are often written as tightly as a haiku.

1.

Like a flash

his love vanishedA trinket gets

dangled

in your world

you reach for it

and it’s gone

2.

Mother, were he abroad

I’d bear the separation

but to live in separate houses

in the same village

is worse than death

A poetess named Vidyā, who may have lived as late as the seventh century and whose poems were later added to Hāla’s collection, captures perfectly the emotional abandonment to love:

You’re rich, that you can chatter

about a night spent with your lover.

The endless teasings, the smiles,

whispered words, and even

his special smell.

Because, O my friends! I swear,

from the moment my lover’s hand

touched my skirt

I remember nothing at all. [tr. by Andrew Schelling]

The twelfth-century classic, the Gita Govinda by Jayadeva, has superb poetry within the frame of the love between Krishna and Rādhā and other gopikas (female cowherds). It also describes the eight different moods of the romantic heroine (the Ashta-Nāyikā). In these eight moods, the heroine is: dressed up for union, distressed by separation, having one’s husband in subjection, separated by quarrel, enraged with her lover, deceived by her lover, missing her husband who has gone away on business and not returned, and going to meet her lover.

The Ashta-Nāyikā have been illustrated in Indian painting, literature, sculpture, and classical dance. In dance, Rādhā is presented as experiencing each of the eight moods in turn until she is assured by Krishna that he loves her and no one else. This has made the Gita Govinda a major influence on the development of classical Indian dance forms.

Heroine Rushing to Her Lover by Nainsukh or family (late eighteenth century). Notice the menacing snakes. Museum of Fine Arts, Ross-Coomaraswamy Collection.

In later centuries, it became a convention to couch love poetry within the frame of what is unattainable. Perhaps the iconic example of that is the poetess and Rajput princess Mīrābāī (c. 1498–1547) whose lyrical songs remain widely popular. An image given to her during childhood began a lifetime of devotion to Krishna, whom she worshipped as her Divine Lover.

I am mad with love

And no one knows my pain.

Only the wounded

knows the agony of the wounded—

the fire raging in the heart.

For you I gave up pleasures,

Why are you making me long for you?

You caused the pang of separation inside the bosom

Now come and quench it.

Khandita Nāyikā (quarreling with her lover), unknown painter (c. 1800). Brooklyn Museum, A. Augustus Healy Fund and Frank L. Babbott Fund.

The classical conventions of any art form are an easy yardstick of excellence but they also freeze the creative expression. There is a repetition of images and tensions and it is a challenge for the artist to communicate something new using the familiar vocabulary. This is when one may need to fashion a new wordbook or see the simplest of images from a perspective that provides surprising new meanings, as is true of haiku poetry.

Here are two haiku gems by Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694):

In the cicada’s cry

No sign can foretell

How soon it must die.

From time to time

The clouds give rest

To the moon-beholders.

The traditional haiku has its own convention of 17 syllables with three lines of 5–7–5 syllables. The power of the haiku is not in the convention, but the image that binds the words and brings out the paradoxical nature of our experience of love and loss.

It is interesting that the central image at the back of the poem rises spontaneously in one’s awareness, and its recognition as a poem is always a thing of astonishment.

Of love and beauty:

What is love?

1.

A mirror to an expansion,

it is like rain

on a mountain path

on a track that goes

round a bend.

Some tracks

fall off the mountain.

2.

I have seen your image now.

The music of your creations

has become one with me

and I know that worship

is the happiness of walking

to the wilderness.

Words bind—

the smile on your face

has liberated me.

A wonderful meld of the personal, social, literary, mystic, and the poetic. Good to see Subhash’s work getting space on SRW…