On Being an American

Changing Worlds

I had grown up in Halethorpe in Baltimore County, Maryland, in a predominantly African-American neighborhood. It was a small community where everyone knew their neighbors, many who were family, and where a number of the homes had been built by my great-grandfather and his business partners. That part of Maryland was not as racially divided as the Deep South, but it was definitely a segregated environment. Eating facilities were separate and department stores in nearby Baltimore would let blacks purchase clothes, but we were not allowed to try on garments nor return them.

Until 1955, area public schools were segregated. My first ten years of schooling was in a school designated for Negroes (as we were called then). Kids in my neighborhood were bused from Halethorpe to the Benjamin Banneker Elementary, Junior, and Senior High School in the “colored” section of Catonsville. En route, we passed the Catonsville High School campus, a sprawling, state-of-the-art facility for white students. When Baltimore County enacted its school desegregation law in 1955, students at Banneker had the choice of remaining there or transferring to Catonsville. I was one of the nine students who decided to integrate Catonsville High, population 1500 as I recall. The situation was not as difficult or tense as in some parts of the country. Yet, it was not easy. For the most part, the nine of us were not met with open hostility, but there were few open arms. Over time, things did improve somewhat and by my senior year I was even selected to narrate the commencement pageant at graduation. I had also done well enough to secure a senatorial scholarship to any college under the umbrella of Maryland’s state university system. I seriously considered the University of Maryland at College Park. However, because Catonsville High had been so socially isolating for me, I decided to go to the historically black college, Morgan State in Baltimore. So to speak, I came back to the fold, where I could feel welcomed.

But once I joined the Peace Corps, I felt part of a team whose players had a shared purpose and like values. We became a very special family, as illustrated by the fact many of us are dear friends who still keep in touch. I learned something I could not have learned at home during that period in our history. I learned to be an American as opposed to being a “Negro in America” negotiating the restrictions imposed by racism. I began to perceive my identity from a wider context than the nurturing community and school where I had lived and studied during my formative years.

The Peace Corps offered me a freedom denied to me in my own country, at least in my part of the country, during that era. I am under no illusion that people ever forgot my color; nor would I want them to; nor did I. The point is that I was less and less defined by my race. There were fewer assumptions based on how I would react as a Negro—more about how I would relate as an American.

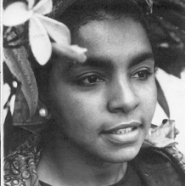

In adjusting to the Philippines, unlike most fellow volunteers, I was accustomed to being in the minority. I now see that my response to being one of a handful of African Americans among an overwhelming majority of white students in Catonsville High turned out to be excellent training for living abroad. Instead of being intimidated because I was different, I chose to hold my head high and to wear my uniqueness with pride and as a badge of honor.

Daring to Take the Plunge

In hindsight, I realize that I really did not know what I was getting into when I joined the Peace Corps. How could any of us have known? It was all so new then. Yet today it is hard to imagine how my life would have been without that initial voyage into living and working outside of the United States.

So much has happened since that muggy, rainy day in October 1961 when we landed in Manila and took the long bus ride to the Los Banos training site with multiple stops in small towns, each treating us to a merienda (a small meal). I have had a rich and fulfilling career, much of which I can attribute to that life-changing start as a Peace Corps Volunteer.

During our Peace Corps training, we had been steeped in cultural awareness by Professor George Guthrie. Once on the ground, it was time to apply that training. Nevertheless, there were at least two occasions that come to mind in which I flunked “Cultural Sensitivity 101”.

Clueless One

In our assigned town, Magarao, Camarines Sur, one Peace Corps Volunteer housemate and I brainstormed the idea of establishing a community library. Thanks to the cooperation of my mother and other family and friends in the United States, the Baltimore Enoch Pratt Library, the Asia Foundation, and the United States Information Service, we amassed a large number of book donations for the project. We set up a community library taskforce, held numerous planning sessions, and assumed our Filipino colleagues were equally keen. Things seemed to be progressing well—or so we thought until we discovered that some Filipino members had reneged on their commitments. In fact, in earlier meetings, a number of the town leaders and teachers had only been polite—telling us what they thought we wanted to hear. Pleasing us for the moment in order to avoid possible unpleasant disagreements was their gentle way of going along with the program but not owning it—perhaps hoping the issue would resolve itself or go away. It had not occurred to the Filipinos that we would see their actions as deceitful or dishonest. Unfortunately, when we learned that not everyone was on the same wavelength, we volunteers became outraged and let it all out. One Filipino male teacher responded in kind, resentful of young American women telling him what to do. Ultimately, through the graciousness of most committee members, we managed to save the day.

From that experience, I learned to probe more gently, but more deeply to get forthcoming answers when soliciting cooperation from others. Had I not been so taken with the project, so full of my own “bright ideas,” I might have picked up on the cultural cues, subtle signs of reluctance, faint unenthusiastic polite compliances. It was never easy, but I became more sensitive, more adept at communicating with my hosts. In the end the library was a success. The town not only provided space and shelving for the books, but also assigned the over-qualified town hall janitor as library attendant. The library remained intact for several years until it was hit by a typhoon, which I learned 15 years later when, as a Foreign Service Officer, I had the chance to visit Magarao.

Clueless Two

Another example of miscommunications occurred in our own Peace Corps household only a month or so after my three housemates and I arrived in Magaroa. It was early January 1962, by which time we were barely settled into our new house, a simple sturdily constructed dwelling with a nipa (thatched) roof and the luxury of electricity, in-door plumbing, and one small screened-in room. As with most volunteers and as was expected of us, we had a maid/cook. Rita Brabante was hired in advance of our December 1961 arrival by fellow Magarao teacher, Mrs. Barameda. Rita was quiet, pleasant, and very helpful as we tried to adjust to our new surroundings. She made a great effort to please us, unaccustomed as we were to managing household help. Unfortunately, in just a little more than a month, Rita decided to quit because “Her mother needed her at home.” In an effort to get to the real reason for Rita’s departure, we sought the advice of a “go-between,” Mrs. Barameda. To our surprise, Rita had several complaints. For starters, we had left her for the weekend with no food. (She did not usually stay overnight; so, we had assumed she would eat at home with her family.) Second, we had failed to provide expected bonuses for the movies or recreation. Third, the four of us constituted too many uncoordinated bosses giving confusing and conflicting directions. And last, but not least, we talked too fast!

Looking back, I believe we were so focused on establishing relations with our fellow teachers and community leaders that we had neglected to concentrate on basic communications with a person supporting us in our own home. Unwittingly, we had reserved cultural awareness for a certain segment of the population. We were able to resolve our differences with Rita thanks to the invaluable skills of Mrs. Barameda, who helped us maneuver through that situation as well as a few other scrapes. Rita turned out to be a good sport, tolerant of our “peculiar” ways. For me, Rita became such a confidant and part of our household that she was one of the people I sought out when I returned to the Philippines in the mid-1970s.

Reentry

But back home, not too long after my return from my volunteer assignment, there would be one last comeuppance on the racial front. Another African American returned volunteer and I went to our alma mater, Morgan State College, on a Peace Corps recruiting trip. Afterward, he and I stopped at a very casual restaurant for a meal, and we were refused service. Bluntly reminded that segregation in my country was alive and flourishing, I was hurt, disgusted. I had left our country to represent our great democracy. Yet, less than 35 miles from our nation’s capital, only one mile away from my old campus, I could still be refused service because of the color of my skin. Fortunately for me that was the last such unpleasant encounter of its kind.

At the end of my volunteer stint in the fall 1963, I joined the Cardozo Project in Urban Teaching, a year-long pilot program in curriculum development utilizing returned Peace Corps Volunteers in an urban setting, Cardozo High School in Washington, DC. I had grown up in a small town. So, while the project was an invaluable experience, I must admit to a degree of cultural shock. For me, working in the rough and tumble of an inner-city high school was quite an adjustment. I found the students a stark contrast to the well-behaved youngsters I had taught in the Philippines classroom.

However, nothing was more devastating that year than the senseless death of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy on November 22, 1963, a tragic day stamped in the memories of so many. For me it was made even more poignant because I had the honor to be one of the two returned Peace Corps Volunteers selected to represent the Peace Corps at the president’s funeral three days later. The other returned volunteer was Thomas Scanlan, who had served in the first group in Chile.

My recollections of my emotions are more vivid than of the proceedings of that sad occasion, handled with the utmost elegance and dignity. The funeral was held in Washington, DC at St. Matthew’s Cathedral and the burial at the Arlington National Cemetery. Cardinal Richard J. Cushing conducted the requiem mass. The cathedral was packed with dignitaries and distinguished guests, family, and friends. I could not help but be in awe of the array of American leaders as well as foreign luminaries such as Emperor Haile Selassie, the Duke of Edinburgh, and King Baudouin of Belgium, all who had gathered to pay tribute to our president.

The assembled group left St. Matthew’s and was led to the motorcade that took us to Arlington National Cemetery. Tom and I were honored to be assigned to the same car as Astronaut John Glenn and his lovely wife, Annie. As the solemn procession of more than 100 vehicles moved slowly along the route, I was profoundly touched by the throngs of bystanders, mourners, lined along the passages to pay their respects to our fallen leader. Despite the crowds, the city was eerily hushed on that cold winter afternoon as we passed through its elegant spacious boulevards and by its monuments to the final tribute to John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who had been a beacon of hope for so many around the world.

The Kennedy Inspiration and the Peace Corps

One event that brought home to me the full significance of the impact the Kennedy era and the Peace Corps experience had on my life occurred thirty years later when I had the occasion to tour the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas and view the exhibit of events related to President Kennedy’s assassination.

The longer I stayed on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, the more it struck me how much President Kennedy had influenced my life. Eventually, I stopped viewing the exhibit and sat on a side bench. I thought of how Kennedy’s call to service in his inaugural address had heightened my interest in volunteering. Even earlier in my junior year in college I had seen two moving television documentaries on volunteering: one about “Crossroads Africa” and the other about “Teachers for East Africa.” Plus, I had gotten to know a number of African students on Morgan’s campus. Those I met were incredibly dedicated and mature compared to American students. These encounters enhanced my interest in working abroad, preferably in Africa. And then as I was about to graduate from college, the Peace Corps was being formed—just what I had been looking for. I took the Peace Corps examination at the earliest possible opportunity. Twelve hours later, I had a telegram offering me an assignment in the Philippines! So, I located the Philippines on the map and responded in the affirmative. It was not Africa, but it was the answer to my wanderlust to serve abroad.

The Peace Corps had set me on a path that otherwise I would most likely never have dared to embark upon. A liberal arts graduate with a minor in education, I was destined to teach in the public school system—a respectable, secure profession, which I accepted as the natural career path for many women college grads at the time.

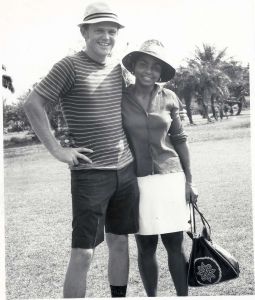

Sitting there in the book depository, as all those memories surfaced, I found myself weeping, not caring who noticed me or what they thought. That day in Dallas seemed to solidify my realization of the dramatic effect the Peace Corps had on me. I thought of all of the wonderful people, fellow volunteers, other Americans, and countless foreign nationals who have been a part of my life during my volunteer years and subsequent overseas experiences; of how the Peace Corps was the foundation for other major decisions, such as joining the Foreign Service. Even more important, it was while I was on the Peace Corps staff in Tanzania in the mid-1960s that I met my fantastic husband, Dick Schoonover, who was serving in our embassy as Cultural Affairs Officer.

I also reflected on how much I had learned from my gentle and gracious Filipino hosts who had helped me develop an understanding of the importance of cultural sensitivity—knowledge that has served me well, especially as a diplomat, in the many countries in which I have lived and worked.

Yes, I thought of the moving funeral ceremonies of November 25, 1963. Yes, I was crying for our country’s incredible loss of our vibrant president, but I was also overcome with gratitude, a profound appreciation of my good fortune to have had the unique opportunity to be a pioneer, a part of Kennedy’s brilliant creation of the Peace Corps at its inception. It was my gateway to many other far-flung places and encounters with so many fascinating people. It allowed me to be a citizen of the world—and a very lucky one at that.

Note: This essay originally appeared in Answering Kennedy’s Call, Pioneering the Peace Corps in the Philippines (edited by Parker W. Borg, Maureen Carroll, Patricia MacDermot Kasdan, and Stephan W. Wells; Peace Corps Writers Edition, March 2011, in honor of the Peace Corps fiftieth anniversary) and was subsequently reprinted in American Diplomacy (March 2011).

This is a moving tribute to the best of kennedy’s leagacies, the Peace Corps. The author correctly chooses to treasure her experience in the Peace Corps and its profound effect on her career and her life rather than to the negative elements of the sixties such as racism. Clearly the author wisely knew how to take the utmost advantage of opportunities. It is very gratifying to learn of her honored place in the funeral of John F. Kennedy. Her inclusion is important for our belief in democracy.

Very well written. I only wish there had been a few more photos like the one of the handsome happy couple.

Meditators to Gloria’s comments. The article is witness to Brenda’s positive spirit.