Pasajs | Passages For San Malo

San Malo, to vini plu mal

Plu gran zombi.

Saint Malo, you’ve become very tough

But you are the greatest spirit. . . .

—Bruce Sunpie Barnes, Le Kér Creole

We need to think comparatively about the distinct routes/roots of tribes, barrios, favelas, immigrant neighborhoods—embattled histories with crucial community “insides” and regulated traveling “outsides.” What does it take to define and defend a homeland? What are the political stakes in claiming (or sometimes being relegated to) “home”? . . . We need to know about places traveled through . . . we need to conjure with new localizations.

—James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century

i set my light on the altar of san malo

—Brenda Marie Osbey, “In the Business of Pursuit: San Malo’s Prayer”

Mennen Bèk San Malo: Remembering San Malo from Neighborhood Story Project on Vimeo.

I.

Rachel: In 2013, Bruce and I went to Dockside Studio with his band, Sunpie and the Louisiana Sunspots, to work on Le Kér Creole, a project about Creole music and language (Barnes, Breunlin, Etienne, and Hampsey, forthcoming). Just outside of Lafayette, the recording studio next to Bayou Teche was quiet; the air seeped in the deep summer humidity. On the first afternoon, Bruce jumped up and said, “I have a song.”

Bruce: It sounded like a voice riding the wind from the east of us. As the lyrics started coming to me, I picked up my piano accordion and began trying to play the melody floating in my head:

Oh San Malo, wiri a wiri ooh!

Oh San Malo, wiri a wiri ohh!

Rachel: Juan San Malo, a maroon leader during the late 1700s, must have come in through the pasaj, or passage, of the bayou. During slavery, slow moving, meandering waterways like the Teche became escapes routes (Hall 1992).

Bruce: The threads of bayous throughout the delta were more kaché, or hidden, and safer than traveling on the heaving Mississippi River. The story of San Malo’s gran kouraj (great courage), and how he was eventually captured, has been told for centuries, and here it was again, transformed into a new song:

San Malo, to kaché dan bwa.

Soldat ye cheché twa.

San Malo, to vini plu mal,

me twa byen plus sal

Saint Malo, you are hiding in the woods.

Soldiers are looking for you.

Saint Malo, you are very bad,

but you are also tough.

II.

Rachel: In the 1780s, when Juan San Malo was enslaved on the d’Arensbroug plantation, the Mississippi River was right there next to him, wild and huge.

Bruce: The plantation consisted of many arpents along the river. Below the natural levee, bottomland hardwood forests and palmetto groves descended into the cypress swamps. Farther south was Lake Ouchas, which had been named after the Oucha Indians whose shell middens were located all over the area.

Rachel: In the 1780s, Louisiana was controlled by the Spanish Empire, but French was still the most widely spoken language. The d’Arensbourg plantation was in an area called Côte d’Allemagne and had been colonized by settlers from Switzerland and Alsace-Lorraine who had lived as neighbors to the French in Europe and were doing the same again in the Louisiana. The language of the plantations was different.

Bruce: As enslaved Africans listened to the French while trying to communicate with each other, they created a Creole language that was built out of defense and could help them negotiate between the many other African and Native American languages that were spoken in the area.

Rachel: Most likely, San Malo would speak of the landscapes and waterways in Creole and piece together how the same places were connected to Oucha landmarks, and the way the colonizers spoke of the land around him. He must have listened to where the Indians had created homes in the water—how you might survive off the land around the river. Ronald Dumas, a historian from the area where San Malo was raised, said that as a child he was told that San Malo hid in the swamp, and when he escaped, he lit the cypress trees on fire.

Maybe he traveled through the smoke in a pirogue, maybe he hid away on a boat traveling down the river. When he made it to New Orleans, he learned that there were a series of bayous and distributaries in the back of the city that were connected to lakes that opened to the sea. On the edge of the Choctaw market near the Bayou Road, you could get in a pirogue and paddle down Bayou Gentilly to Chef Menteur, or Bayou Bienvenue to the edge of Lake Borgne (Hall 1992; Lewis 2015). At the time, this area was called Bas La Fleuv, the bottom of the river.

San Malo took these pasajs out of the city. Around the Rigolets and on the far ends of Lake Borgne, the maroons found other shell middens from Indian settlements. The high ground they created could be a place to make a home. Along the bayous that wove through the area, they logged cypress to build shelters and sold lumber to local sawmills (Hall 1992).

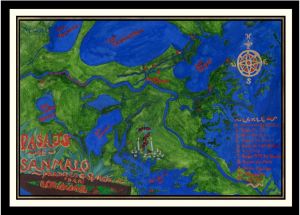

Watercolor map by Rachel Breunlin of the pasajs, or passages of San Malo and his band of maroons adapted from Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s Africans in Colonial Louisiana and other historical maps, includes offerings to San Malo made at Fleming Cemetery in Lafitte.

San Malo fell in love with a woman named Cecilia, who, according to colonial authorities, was “his inseparable companion in all his exploits.” Together, they helped runaway slaves join the maroon villages. Children could grow up without the fear of the whip. Nearly a hundred years later in the late 1800s, Lafcadio Hearn spent time with a group of Filipinos who settled in the same area. Here is his account of the sunset at San Malo Bayou:

The bayou blushed crimson, the green of the marsh pools of the shivering reeds, of the decaying timber-work, took fairy bronze tints, and then, immense with marsh mist, the orange-vermilion face of the sun peered luridly for the last time through the tall grasses upon the bank. Night came with marvelous choruses of frogs the whole lowland throbbed and laughed with the wild music—a swamp hymn deeper and mightier than the surge sounds heard from the Rigolets bank: the world seemed to shake with it! (Hearn 2001: 90)

By the late 1780s, plantation owners began to organize against the maroons. They pooled their money and helped fund militias to stalk their camps. Records of the Cabildo document these missions through the waterways and into the swamps. San Malo, Cecilia, and others were captured and brought into the city. [They were] accused of inciting an uprising, and Spanish authorities said their quick inquisition led to San Malo’s confession. On June 19, 1784, he was hung in Jackson Square. Cecilia said she was pregnant, and avoided death, but a number of their companions were also killed. San Malo’s body was left to be eaten by the carrion crows. Any depiction of him, they said, would be destroyed.

But it didn’t work. His story became folklore. More than a hundred years later, in “Dirge to San Malo,” a Creole song collected by George Washington Cable in the 1800s, he does not confess. He stands strong with his people:

Yé mandé li qui so comperes.

Pov St. Malo pas di’ a-rein!

They asked him who his comrades were.

Poor St. Malo said not a word! (Cable 1959: 418–419)

The maroons who survived the Spanish crown’s attack relocated to a barrier island off of Barataria Bay, but the names of the bayous in the area around la bas le fleuv, Bayou San Malo, and Bayou Marron continued to hold the mystique of the maroon settlements.

Around the same time in New Orleans, Raoul Desfrene, a “French Negro” visited the home of vodou priestess Marie Laveau and saw a statue on her altar called Saint Marron. Years later, he told an interviewer from the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writer’s Project Saint Marron was “a colored saint white people don’t know nothing about. Even the priests ain’t never heard of him ’cause he’s a real hoodoo saint”. (Tallant [1946] 1998: 78)

Raul remembered going on Monday nights to a vodou gathering, called a parterre, with Marie Laveau over at Mama Antoine’s house on Dumaine Street. Parterre translates from the French or Creole into English as flowerbed or orchestra, but could mean, in a broader sense, a well-organized mélange of different offerings and music. Here is a description of what he saw:

A feast was spread for the spirits present on a white tablecloth laid on the floor. The food included congris, apples, oranges, and red peppers. There were lighted candled in the four corners of the room; Raul recalled their colors as red, blue, green, and brown. A Negro named Zizi played the accordion. (Tallant [1946] 1998: 78)

Far from the bayous of San Malo and Marron, the women of the parterre danced to the breath of the accordion.

Bruce: The spirits love the sound of the accordion.

Rachel: It must be the yearning feeling. The memory of San Malo, so close to memory like its sister bayou in St. Bernard Parish, was perhaps channeled into the image of Saint Marron.

III.

Now I will have some full disclosure. As an anthropologist, I was raised in the trade of Marie Laveau. As I was going through graduate school, my advisor, Martha Ward, was working on a history of the vodou priestesses, and as I finished my degree, her book came out (Ward 2004). It was a volatile time in the scholarship of the healing arts in Louisiana. Threats and spells and more scholarship arrived (Fandrich 2004; Long 2007). I was shocked. But not as shocked as when the subject of my own thesis, Joseph Glasper Sr., whose family was from a Creole community along the Mississippi River in New Roads but who had been raised in the city, shot and killed a vendor in front of his barroom in Tremé after the musician Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen’s jazz funeral (Breunlin 2004).

Yes. Up until then, I had been a naïve researcher, and I was just as naïve in the realm of the spirit. I wasn’t sure how I was going to finish my project. I could see no bon pasaj. My friend Michel told me to find a few dollars and she would take me to St. Jude’s to light a candle. A candle to the Patron Saint of Lost Causes. The candle worked. Sometimes passage comes from a route you didn’t expect.

Bruce: I first learned about San Malo being transformed into a spirit when I worked in the Barataria Preserve. He came up all over the area. Tony Ting, whose family was part of the Filipino community connected to Manila Village, said his people danced on the shells of shrimp barefoot to traditional Filipino music on the same island where San Malo’s people had lived. On All Saint’s Night, the Fleming Cemetery in Lafitte was lit up to honor the spirits of the ancestors. After the Cajun families had left the cemetery, Creole and Native Americans came out to give their food offerings. They would leave statues of snakes, palmetto crosses, golden horseshoes, and glass beads for San Malo. Later, I heard the owners of a botanica on Barataria Boulevard talking about how people still lit candles for him. He was like St. Expedite—a spirit you call not just for everyday things but when there is a real emergency; when you need the strongest support in the moment. But I never saw an image of San Malo.

Rachel: Vodou in Louisiana developed through direct connections to Africa, not just an inheritance from the Caribbean, but perhaps due to years of persecution, very little has been openly shared about how the local history is embedded in people’s practices. In 2008, an anthropology graduate student named Erin Voisin worked on a master’s thesis to learn whether St. Marron, or his historical counterpart, San Malo, have stayed on the altars of the city. She talked to different vodou priestesses and scholars and found, to her disappointment, that there were no physical representations of either available to the public (Voisin 2008: 65).

IV.

Which leads us to our final stories of San Malo. While Bruce and I wrote out San Malo’s song and translated it into English for Le Kér Creole, we wondered how we would connect it back to parts of South Louisiana where the language was mostly a memory.

Bruce: Around the same time, I was organizing a series of concerts with L’Union Creole for the grand opening of New Orleans Airlift’s Music Box Village in November of 2016. I asked Dédé St. Prix from Martinique, Segenon Kone from the Ivory Coast, and Opera Creole to join my band for a concert where we would incorporate Creole music into the musical houses. Airlift had created them after Hurricane Katrina, but this space in the Ninth Ward was their first permanent home.

Rachel: I told Bruce, “If you are going to play San Malo’s song, let’s try to make a broadside dedicated to him and the world he created. We can imagine the Music Box as a maroon village.”

Bruce: With no images, we had to create a poster from scratch. We asked artists Francis Pavy and Kiernan Dunn to help us. We drove to Chef Menteur and photographed the landscape where San Malo used to live. We went into the archives that Gwendolyn Midlo Hall spent so many years researching and photographed the original Records of the Cabildo. And then we went to the F&F Botanica on North Broad Street and asked our friend Jonathon Scott if there was a candle to San Malo. If any of his customers ever asked for him. Jonathon said, “San Malo? No. Saint Maroon, yes.”

Rachel: His representation was anything but local. Jonathon showed Bruce a statue of Saint Martin de Porres. From Lima, Peru, he was the son of a Spanish man and an African or Indian woman from Panama who had been a slave. Bruce photographed him with his broom, and Francis placed the statue sweeping the waterway along Chef Menteur. Behind him is a page from a trial transcript where it is reported that Spanish colonial officials tracked other maroons who were in la compania de San Malo (in the company of San Malo), in the same area. Kiernan took these layers of images and screen printed them onto shimmering blue paper.

Bruce: While we were organizing the poster, Jonathon told us Saint Martin’s feast was on November 3, right around the dates of the concert.

Rachel: Thinking about the altars inspired us to make one for San Malo at the Music Box. If there wasn’t any iconography for the resistance leader, we would create it ourselves. When Erin interviewed Brenda Marie Osbey about her poem to San Malo, the poet told her she continued to do research on the maroon, and that she was creating a series of poems called “The San Malo Cycle”:

As I get older, these kinds of people become more and more significant. They come to symbolize something that, although I’ve always been aware of them, they could not possibly have meant to me what they mean to me now. (Voisin 2008: 63)

As we created the San Malo altar, the same deepening occurred. Bruce went out to the swamp to photograph, and I created a series of watercolor prayer cards. For Black History Month, we worked with the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park and the New Orleans Jazz Museum to install another one at the Old U.S. Mint. In a site of official memory, it felt good to add a connection to the parterres of the past. To tell the decolonized history in the same building where the Spanish Records of the Cabildo are housed. We asked visitors to tell us their own hopes of freedom and looked for the altar’s next home.

Bruce: On Saturday, March 17, 2017, we built the installation at Bullet’s Sports Bar in the Seventh Ward, one of the neighborhoods of New Orleans where Creole was spoken and Mardi Gras Indians have a strong following. Years ago, the Big Chief of the Cheyenne Hunters Mardi Gras Indian tribe, Ferdinand Bigard, told me about San Malo.

Rachel: We thought other Mardi Gras Indians would be interested in the history, as many tribes mask to pay homage to runaway slaves and their connections to Native American communities.

Bruce: Many words in Mardi Gras Indian songs can trace their roots back to Creole as well. For the night at Bullet’s, we invited some of our friends who’ve masked over the years to come sing with us.

Rachel: When Bruce took out his accordion and started to sing in Creole, older men in the audience remembered phrases from their childhood and started shouting them out: “Me wi, mon ami!” But yes, my friend . . .

Bruce: That night, Clarence Delcour, the Big Chief of the Creole Osceola, told me he did not remember a lot, but one phrase in Creole stayed with him since he was a child. When Mardi Gras Indians gathered on carnival morning, Donald Claude’s uncle would tell them before they left the house, “Onn é tou ansanm.” We are all together.

Rachel: At Bullet’s, Clarence and Donald sang with Fred Johnson, Ronald “Buck” Baham, and other Mardi Gras Indians while people made offerings to San Malo’s altar. For a night, when they danced, they danced for the maroons, the runaway slaves who followed the pasaj and made their home on the shell middens of ancient Indians.

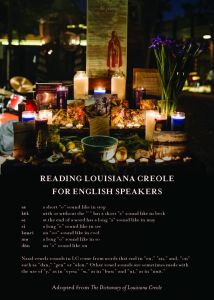

San Malo altar installed for L’Union Creole’ s performances at New Orleans Airlift’s Music Box Village grand opening with a key for reading Creole.

Louisiana Creole is a Francophone language created by enslaved Africans during the 1700s, but adopted by people of all backgrounds as a language of intimacy, family, and community. In South Louisiana, lullabies were hummed, prayers were called, opera was performed, zydeco was danced, and Mardi Gras Indian chants were sung in Creole. One of the most endangered languages in the world, it is still spoken by tens of thousands of older people who grew up with it as their mother tongue. You can hear echoes of it in the inflection of speech, phrasing, and words in South Louisiana English. An oral language, Creole was rarely written, and so this music, art, and writing project is our ongoing experiment in using the pan-Caribbean orthography to share the language as written text.

Works Cited

Barnes, Bruce, Rachel Breunlin, Leroy Etienne, and Matt Hamspey. Forthcoming. Le Kér Creole: Compositions from Louisiana. New Orleans: The Center for the Book at the University of New Orleans.

Breunlin, Rachel. 2004. “Papa Joseph Glasper, Sr. and Joe’s Cozy Corner: Downtown Development, Displacement, and the Creation of Community: A Thesis.” The College of Urban and Public Affairs, University of New Orleans.

Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cable, George Washington. 1959. Creoles and Cajuns: Stories of Old Louisiana. Edited by Arlin Turner. New York: Peter Smith.

Fandrich, Ina Johanna. 2004. The Mysterious Voodoo Queen, Marie Laveaux: A Study of Powerful Female Leadership in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans. New York: Routledge.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. 1992. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Hearn, Lafcadio. 2001. Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn. Edited by S. Frederick Starr. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Lewis, Josh. 2015. “The Disappearing River: Infrastructure and Urban Nature in New Orleans.” In Deltaic Dilemmas: Ecologies of Infrastructure in New Orleans. PhD dissertation. Stockholm University.

Long, Carolyn Marrow. 2007. A New Orleans Vodou Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Osbey, Brenda Marie. “The Business of Pursuit: San Malo’s Prayer.” In All Saints: New and Selected Poems. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Tallant, Robert. 1998 [1946]. Voodoo in New Orleans. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company.

Voisin, Erin Elizabeth. 2008. “San Malo Remembered: A Thesis.” Department of Geography and Anthropology, Louisiana State University.

Ward, Martha. 2004. Voodoo Queen: The Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.