Pii Mai in the Blue Ridge Mountains: Conjuring Laos at Wat Lao Sayaphoum

Noubath hands me a silver offering bowl and fills it with three small bananas, two sesame-covered fried desserts, a lunch-box-sized orange juice, and a Kellog’s Rice Krispies Treat in its crinkly blue packaging. Folding a piece of lined notepaper with quick movements, she transforms it into a neat cone and tucks my bills and two yellow flowers inside.

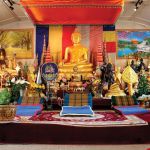

In a few moments, I was ready with offerings for Pii Mai, or Lao New Year. I was sitting with the Phapphayboun family on the soft carpeted floor towards the front of a small temple. The altar, a richly ornamented collage, shone brightly, and at its base, small bowls of food, candles, and white blossoms were arranged on trays. A monk sat below the large gold Buddha at the altar’s center, twisting a mass of thin, yellow candles. The room grew quiet, and Khamsi and a few other men near the altar began the ceremony with words of welcome in Lao. The monk lit the candles, and as the call-and-response chanting in Pali began, he slowly turned the growing flame over a bowl of water.

At Wat Lao Sayaphoum, a small Buddhist temple in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Lao New Year celebration was underway.

From Vientiane to Morganton

“The continuing thread between my homes is Lao-ness.”

—Toon Phapphayboun, July 28, 2014

I met the Phapphayboun family in Morganton, North Carolina, entirely serendipitously. At the time, as part of my graduate studies in folklore at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, I was seeking connections to the Hmong community in the western part of the state. I had just left my job at The Textile Museum, in Washington, DC, and naturally, I was curious to know whether there were textile traditions I could explore in my new home.

Instead, I met Toon Phapphayboun at a Hmong New Year festival, and she invited me to join her for dinner at her sister’s Morganton restaurant. The Phapphaybouns’ enthusiastic welcome and love of their country pulled my graduate work in an entirely different direction. Between November 2013 and May 2015, I made the three-hour drive from Chapel Hill to Morganton many times, and I overlapped with some of the family in Vientiane, Laos, for six weeks during 2014. I completed more than nineteen interviews, many with Toon—who became my primary interviewee and collaborator—acting as translator. I continue to be great friends with the Phapphaybouns, who are generous with their stories, humor, and hospitality.

Toon, one of three daughters and a son, was the first to leave Vientiane in 1980. She escaped when she was just fourteen by canoeing and swimming across the Mekong, fleeing a repressive regime heralded by the rise of the communist Pathet Lao party five years prior. She arrived in Los Angeles in 1981. Eleven years later, she successfully helped the rest of her family leave Laos for the United States. After living in California and Connecticut, the Phapphaybouns almost entirely reunited in Morganton, North Carolina, in 2003. (Toon’s older sister, Khattana, lives in Texas but continually jests she needs to find a way to finally join her extended family in North Carolina.)

When I ask the Phapphaybouns and their relatives why they chose to settle in Morganton, a small city surrounded by hilly countryside, they always provide the same answer: It is a little bit like Laos. The two distant places—one in Asia, one in North Carolina—share a similar mountain foothills landscape, a tie viscerally felt by the Lao families. When Toon’s brother-in-law Daniel Phrakousonh visited Morganton before moving there, he thought, “It looks like Laos! A lot of trees, a lot of mountains. Plus, at that time, I was considering the cost of living . . . When I came down here it was quiet [and] there was a lot of time for family and outdoor activities.”

Families like the Phapphaybouns are transforming the South. Asian-Americans are one of the fastest-growing populations in North Carolina.[1] The experiences of Asian-Americans, and the way in which they adapt and contribute to southern culture, are essential in understanding the contemporary South.

Wat Lao Sayaphoum

Wat Lao Sayaphoum is situated in an undeveloped, hilly landscape roughly thirteen miles from downtown Morganton. Led by Toon’s step-father Khamsi Bounkhong Siluangkhot, the Phapphayboun family helped establish the temple in 2003 in his living room shortly after he and Noubath, Toon’s mother, arrived in North Carolina. Back then, roughly thirteen Lao families lived nearby, and with their support, Khamsi and the management team transformed a nearby rental house into a temporary temple. In 2005, with community donations, temple leadership bought a trailer on a plot of land in a hilly, largely undeveloped area south of the city.

Ten years later, Wat Lao Sayaphoum is host to weekly worship services and festival celebrations and serves as a residence for visiting monks. The building was erected quickly, as Toon said, the community “did the Lao thing with construction—they just built it.” Wat Lao Sayaphoum, like the Buddhist temples of Laos, is in a constant state of improvement and beautification. The primary temple is in a transformed carport, built by community volunteers. Indoors, the structure’s simplicity is masked by the oranges, golds, and reds of Buddhist objects—each one mailed, carried over in a suitcase, or important from Asia via specialty groceries.

Today, the nearby Buddhist Lao community has more than doubled in size and has nearly outgrown the space.[2] County building codes are also a pesky challenge. Dara, Toon’s younger sister, is helping the temple’s management team to consider new locations—but when I was visiting Wat Lao Sayaphoum in 2013−2015, it was at its peak.

Pii Mai in Morganton

On this Saturday in April 2015, as Noubath filled my offering bowl, the wider community came together at Wat Lao Sayaphoum in celebration of Pii Mai. The temple was dressed to the nines. The fountain by its entrance was running with water, and a table with flowers was placed in front of the Nang Torlanee statue (a Lao-Buddhist Mother Earth). To her left, several gold Buddhas sat on a shelf in the sunshine, flower petals at their bases, to be blessed and doused with water. Once the ceremony inside drew to a close, the celebration spilled outdoors and eventually down the hill to a stage and dancefloor.

In Laos, Pii Mai is a three-day national celebration that combines sacred reverence with raucous partying. It occurs in mid-April, the hottest time of the year. For blissfully practical reasons, and to usher in the rainy season, it is a new year’s custom to splash water on one another. This can be as gentle as a wet hand on the back of the neck—or as wild as water guns, water balloons, and buckets allow. Temples across Laos are filled with candles of all sizes, orange marigolds and other flowers, and the bases of altars overflow with offerings. Buddha statues are brought outdoors so that they too can be sprinkled with water and renewed for the coming year.

Every Pii Mai tradition is reincarnated at Wat Lao Sayaphoum—adapted to North Carolina, but recalling the grandeur of its original form. In Laos, the water to rinse Buddha figures may flow from a centuries-old carved naga (a river dragon and sacred symbol and protector). In Morganton, a community member has crafted a naga trough from plywood and painted it yellow and red. In place of banana leaves, Noubath folded my bills and a few flowers into a notebook paper cone. There are also plastic imitations of the grander banana leaf offerings spread throughout the altar. In its original form in Luang Prabang, Pii Mai includes a reenactment of a folk tale with seven young girls, or “princesses,” dressed in gorgeous traditional silk sinh. At Wat Lao Sayaphoum, the dress is equally vibrant and formal—but the rules are more lax. In 2015, nine girls were invited to join (why not?). In communities across Laos, Pii Mai spills beyond the temple into the streets. At Wat Lao Sayaphoum, and across the US, celebrations are restricted to temple grounds. Chicken, split duck heads, and Lao sausages are grilled, the pho Dara (Toon’s sister) donated is heated up and served, and beer and whiskey is passed around. As the music starts from the stage, the party begins.

Wat Lao Sayaphoum provides a space where the Lao Buddhists of Morganton can perform religious rites in a context made by Lao, for Lao. To recreate important acts of personal devotion, the temple community must reinterpret the historical traditions of Laos for their utility in the North Carolina foothills.

The Lao community also willingly reinvents everyday spiritual traditions for their present needs. Ceremonies at Wat Lao Sayaphoum deviate from the Buddhist calendar and are instead held on Sundays in deference to the workweek. The tak baht is also reimagined. Rather than walking the surrounding streets to receive daily offerings, the monks of Morganton rely on a synchronized delivery of meals by the laity. Families bring them their lunch three days a week, and the larger community donates simple foods the monks can prepare on their own the remaining days. This flexibility ensures Wat Lao Sayaphoum is a vital community gathering place that is easily accommodated into life in Morganton.

As the temple grew since its establishment in 2010, its meaning and significance also increased. As Air Ammalathithada, Toon’s sister-in-law, explained to me, the temple “is part of a family, like in Laos. When we have our traditions, we go to the temple, and I feel like I’m in Laos.”

For the Lao who visit Wat Lao Sayaphoum—for Pii Mai celebrations or quieter, mid-week retreats—the temple and its altar are a North Carolina depiction of their neighborhood temple in Laos. Reinvented traditions recall much grander versions of the originals in Laos. The red-painted aluminum siding of this carport temple is a stand-in for the gilded walls of grand Lao temples. This intimate connection back to Laos, conjured in the minds of those who visit, honors both group and individual beliefs, and proclaims you belong here. As folklorist Debra Lattanzi Shutika writes in Beyond the Borderlands: Migration and Belonging in the United States and Mexico (2011), “The sense of belonging is constituted through shared meanings and . . . can include places that are physical, virtual, or imagined.”

Wat Lao Sayaphoum is both grounded in Morganton and part of Laos. On festival occasions such as Pii Mai, these intertwined worlds are on display for first-generation immigrants, their children and grandchildren, friends, and colleagues—and perhaps, are drawn a bit closer together.

Portions of this essay were originally published as “Home in a New Place: Making Laos in Morganton,” Southern Cultures, Vol. 22, No. 1, Documentary Arts.

Hear the sounds of Pii Mai at Wat Lao Sayaphoum in “A Trailer, a Temple, a Feast: Making Laos in North Carolina,” Gravy Ep. 31, Southern Foodways Alliance.

For more on the Asian-American experience in the South, see Southern Mix, a new oral history project collaboration between the Carolina Asia Center and the Southern Oral History Program.

Note:

[1] In 2000, the US Census recorded that North Carolina’s Asian population was 1.4 percent of the entire state. By 2010, the figure rose to 2.6 percent.

[2] There is a large Hmong population in western North Carolina, many of whom were resettled refugees from the US’s Secret War in Laos. Unbeknownst to most people, the US government conscripted some 40,000 Hmong soldiers (an ethnic minority from the highlands of Southeast Asia) to combat the rising tide of communism. While Hmong are also from Laos, they are culturally distinct from the Theravada Buddhist Lao community. visit www.southernmixvoices.com.

ສະບາຍດີ ຢາກຂໍຄວາມຊ່ວຍເຫຼືອແດ່ ມີໃຜຮູ້ ພຣະຍາພໍ່ຂັນຕຽນ ຂໍກະລຸນາຊ່ວຍບອກເພີ່ນໂທຫາ ຂພຈ ແດ່ 402-983-0399 ຂໍຂອບໃຈ. Tou Lor