Portfolio: Future Conditional

FUTURE CONDITIONAL

Lynching. Lynching. It means an extrajudicial murder, usually carried out by a mob, usually to bring what that mob thinks of as “justice.” Usually, but not exclusively, the method of lynching is hanging. Usually, historically, there were other means used as well: beating, shooting, evisceration. Usually, traditionally, it was perpetrated by mobs of white Americans, white Southern Americans against Black Americans: including women and children, but men mostly; it didn’t seem to matter. In California, mobs lynched Chinese-Americans, white Americans were lynched, Mexicans, Jews, Italians, Native Americans too. The list goes on. As Bobby Kennedy said, “A mob asks no questions.”

As Abraham Lincoln said, “There is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.” And yet, mob law persists, perpetrated by racists or bigots or zealots in the name of religion or politics, fundamentalism or conservatism or fascism or xenophobia or just plain hatred, and encouraged by clerics and cult leaders and police chiefs and even by the president of the United States. According to an investigative article in the Guardian, between 1885 and 1915, an estimated 2,812 Black men were lynched.1

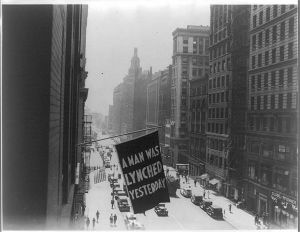

From 1920 to 1938, in front of the NAACP headquarters in New York, a banner was hung on days when its message was literally true; its message was: “A MAN WAS LYNCHED YESTERDAY.” It’s not clear how many times the banner appeared, but Wikipedia reports that it was flown “73 times in the period for lynchings in the state of Georgia alone.”2

Flag, announcing lynching, flown from the window of the NAACP headquarters on 69 Fifth Ave., New York City. Library of Congress.

Rodney King asked: “Can’t we all get along?” Eric Garner and countless others provided a grisly answer to King’s question with their final words: “I can’t breathe.” It’s a tragic call and response that has always undercut America’s claim of “liberty and justice for all.” Over and over and over again.

Sadly, lynching is as American as apple pie. Or peach pie. Or pecan pie. What a horrible legacy for a country to have. For MY country to have. We’ve always grappled with our baser instincts, our instincts for revenge and intolerance and vigilantism, but at some points during my life, it seemed maybe things would get better. Right now, late 2020, I’m a little hopeful even. Maybe it’s just my nature, maybe it’s the enduring power of the #BLM movement. Maybe it’s some strange feeling that, post-Trump, the pendulum of hatred can and will swing back into the realm of love and acceptance. Not all the way, mind you (my expectations are not that insanely hopeful), but, you know, just a little bit. And maybe even a little bit more later on.

Still, that hasn’t happened yet, and lynchings are still happening. Cutting lives short in the name of some perverse notion of justice or even in the name of law and order. Each life cut short had potential attached to it, the potential for a human to become something, to help others, to change the course of history or to simply make someone smile. Each lynching erased all such potential.

* * * * * *

That’s what this project, “Future Conditional,” is about, in a nutshell: imagining the lives that might have been led if they hadn’t been cut short. Each lynching erased the potential these lives had and, in these few “historical” marker mock-ups, I both create and commemorate what might have been. I’ve been making art in this vein for over a decade, subverting the format of the historical marker to highlight some of America’s most pressing political and social issues. To see my work in this vein, click here.3

* * * * * *

A procedural note: I made up each name. Pulled from thin air, or something I read long ago or wherever. Any similarities to persons living or dead is pure coincidence. I made up, obviously, their future lives, as bakers or lawyers or fathers or what-have-you. I tried not to make them all remarkable, and, in fact, for me, the most moving ones are the most ordinary. I made up their ages, too; the only part of each piece that is factual is the reason that they were attacked. So many lynchings were perpetrated for so many petty reasons. It’s almost as if there were a blood thirst amongst the populace and a switch that turned it on with the slightest touch. I chose a victim mix of Black and white and unspecified (though most of the unspecified were, in my head, Black, as the majority of lynching victims were), a mix of male and female, various ages, and though the places are not mentioned, the murders I highlighted happened in Virginia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Illinois, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama.

I did all the inventing for a number of reasons. There are plenty of historically accurate listings of lynchings that can be found with a simple Google search. I easily could have used actual names and actual details of lives cut short, but those people have actual living relatives somewhere and I did not want to co-opt their family history for my own art project. Also, my hope was that making them more fictional would make them more universal. Because, sadly, this kind of violence is universal.

Lastly, the dates on the markers range from 1965 to 2020. I reasoned that actual historical markers are put up anywhere from a few years after the event they mark to a few decades after. I used 1965 as the earliest date because it was the year of the Selma to Montgomery marches and the infamous “Bloody Sunday” attack on Civil Rights marchers, led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams. I used 2020 in order to reference the Coronavirus and to signal that lynchings continue to this present day.

A personal note: This stuff is so very horrible. Researching these atrocities is emotionally trying, crying is common. It shakes a soul to know what humans can do to each other. It shakes a white man’s soul to know what other white men have done and continue to do to Black men and to others and even to each other. It shakes a parent’s soul, a sibling’s soul, a son’s soul, to imagine the abrupt loss of life and the sad tragic impact it would have had on loved ones. It shakes an American’s soul to know that all this hatred made manifest is not just our past, it’s also our present.

Now is the time for all of us to be, not just not a racist, but to be actively engaged in becoming an anti-racist, in the hope that racism and its horrible manifestations are not a part of our future, too. (Click here to watch Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, talk a little bit about this pro-active stance.)

A little note for the grammarians in the bunch. “Would have been,” as used in some of these imagined “historical” markers is the “perfect continuous conditional tense.” Still, I liked “Future Conditional” as the title, as it both invites the consideration of verb tense names and sums up the focus of this project.

1 https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/apr/27/lynching-naacp-photographs-waco-texas-campaign

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_man_was_lynched_yesterday_flag