Portfolio: Paintings

- Firefly, 1993

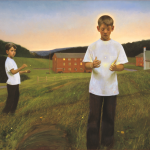

- Young Life, 1994

- Heartland, 1994

- Estralita, 1994

- Homecoming, 1995

- Magical Thinking, 1998

- The Box, 2002

- Leaving Eden, 2002

- The Golden Age, 2006

- Via Mal Contenti, 2006

- A Glory of Painting, 2009

- Inheritance, 2010

- Open Gate, 2011

I live in a strange kind of “all-time”.

No one can know what’s “normal” for others, because we all experience life through our own lens. But, it has been pointed out to me that my way of viewing reality is a tad unique. No doubt it stems from my upbringing in the South, the storytelling tradition and the religious heritage and emphasis on morals and finding “meaning,” but also on my constant discipline as an artist to keep the whole arch of one’s life ever present in the everyday.

My wife and I live in my childhood home in Columbus, Georgia. The house, located in Midtown, the Park District, was built in the late thirties. My father bought the house from his sister, Martha, who was married to the mayor, C. Ed Berry. Berry was a good-ole boy, best friends with Lester Maddox. The house had been on a dead-end street at the bottom of a hill surrounded by natural woods. There was a spring across the street in the woods that formed a creek, which ran through our backyard. Our swimming pool, the oldest continuously operational pool in Columbus, had originally been spring fed. The neighbor to our east had dammed up the creek with bricks and had goldfish in their little pond. There was a waterfall. Few of the yards had fences so we roamed throughout the entire neighborhood as if it were all our yard. The woods, which continued on a quarter mile to the south and a half mile to the west, were our shield from the other parts of town that we preferred not to think about. “Bougahville,” we called it, where the mill workers, poor whites, and African Americans lived (of course, in the fifties and early sixties my parents didn’t use that phrase).

The forest’s trees were ancient: giant oaks, sweet gum, and sycamores. A mossy path led from the corner of our yard into the deep woods. Sometimes hobos would come stumbling out of the path or big dark women with straight backs and colorful fruits atop their kerchiefed heads would appear. It was very exotic.

At some point, the woods began to get mowed down. Our Eden destroyed. They had plans for a shopping center. It remained a grassy field for much of my boyhood. They put an A&P in a corner of it, and built the television and radio station WRBL TV3 and Big Johnny Reb Radio. This field was where I spent most of my afternoons growing up. We played “Combat” (our version of manhunt) in a four-block radius with the hub being our yard. You had to get back to base unseen. I’d ride my bike across the high grass as low-flying B-52s dropped DDT to kill fire ants. My brother and I yelling up to the yellow dust as we rode, “It’s raining, it’s raining!” We’d set fire to the field and run inside and call the fire department and hide and watch them put it out. We could have easily burned our house down. We stood on the hill and watched the civil rights marches as they’d come through Columbus. In this field I went out and picked up an Indian arrowhead when a bulldozer had begun to cut the street through. As there was not much commercial air traffic in South Georgia in those days, in this field I saw my first commercial airliner jet stream; my brother told me it was the bomb. “Hit the dirt, it’s the end of the world.” Crying in a ditch for an hour expecting everything to end soon. The Cuban missile crises had laid the groundwork for the age of anxiety; we were ripe and eager participants. Many of my paintings feature that field. It is where I played and where my imagination still plays. They were good days. We were middle class, white. Generally, the days were long and safe. We were outside all the time. Free and roaming. We’d pick up RC Cola and Coca-Cola bottles and redeem them to get into the movies at the Georgia Theater or the Bradley. The black-and-white newsreels, Patsy Cline, Roy Rogers, Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan. One time Vic Morrow from the television show Combat came to Columbus. I got on my hands and knees and crawled below the legs of the crowd to get to the front of the stage and get his autograph on an 8×10 black-and-white glossy photo. I felt like anything was possible. If you tried, if you were willing to crawl on your belly like Vic Morrow through the mud, you could do anything. That kind of manifestation was reinforced by my alcoholic Baptist father. If I got in trouble as a teenager, my punishment was to read The Power of Positive Thinking and You Can If You Think You Can by Norman Vincent Peale. At that tender age, the message took. I believed in the power of belief. And this mindset served me well when I moved away at age eighteen to Philadelphia with a four month old and young wife in tow. I worked at UPS all night and went to Art School all day (at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts). My religion and my “positive” outlook were important to me then.

There is something about aging that slowly tarnishes the bright spirits of childhood. Our experiences teach us slowly that reality has its own way with us regardless of our belief system.

This past fall, my youngest son, Eliot, passed away. He was twenty-seven. He had struggled for more than ten years with addiction. He’d been sober, had a wonderful girlfriend, was working for a big tech company in San Francisco, when he quickly relapsed and accidentally overdosed. It is the kind of tragedy that is unimaginable and unsolvable. He was loved by his many friends. On the beach in California at his memorial, they were all in shock. How could this have happened to Eliot? He was the funny one, the intelligent, sensitive one, who kept them all balanced and offered a healthy perspective on life. There are no words. There is nothing anyone can say. Sometimes tragedy intercedes and has its way with us.

Does it destroy my worldview—the philosophy of manifestation that I, like my father, preached to my sons, “You can do it,” “Believe it and it will happen”? Not completely. Instead it enlarges it. Perhaps both realities co-exist and are not mutually exclusive. Perhaps we do create our own reality, we can manifest in this life, but chance, accident, chaos can intercede at any moment, anything can happen. And it is ok. It is all ok.

Losing a child makes living in the past more painful than before. All of the “what ifs” and “could have beens” can terrorize us. But, we will all have loss. We will all experience suffering and grief in this life. This is the lesson to be learned. We have to become a larger vessel. We have to embrace life with all of its joys and its sorrows. And in this way, it is like living in “all time.” We love the past in a nostalgic way, knowing that it will never be that way again. We loved the way things were; we loved those in our family who are now gone; we have to embrace the passing of time like we embrace the passing of our loved ones. As a painter, this is a constant practice. We are looking back to our past, our personal history, and to art history for inspiration, but we bring it into the present moment and live our whole life throughout the course of making a painting. We know that the work will live on beyond us. People will be looking at it, trying to make sense out of it, long after we are gone. We can imbue the paint with all of our feelings about life, with every ounce of our being, but then we have to let it go, send it into the future, and hope that someday, it touches someone, that someday it will mean something to someone, it will remind them of something in their own life, some distant childhood memory, some spark, some moment when they felt fully alive. That’s what art can do—wake us up and remind us of who we are, who we were, and what we might become.

amen.

What wonderful work! The ideas in your essay are so visible in your paintings. Please let us know if there will be an upcoming opportunity to see some of your work in person.

I love this story…. You have a way with words….details…

I am a new admirer of your art work and thank you for sharing

Your heart and your painting.

I have recently been introduced to your beautiful work and life stories. I feel fully inspired to get my paint thoughts out onto the canvas, even more so now, for this. I have two young sons and feel a all pervading sadness for you in your loss…at the possibility of such loss. And admire your strength and tenacity; a message to us all. Kia kaha ra! Let there be light! And thank you.

I’ve read a bit about you, seen the movie with you and Betsy, SEE, and videos on your website. I have garnered from your profile that you are a remarkable artist, a wise man and that you and Betsy are good people. When you say that at one time you considered the ministry, I would say you do ministry through your writing, speaking and paintings. Interestingly I was raised as a strict Baptist in rural Maine, with my own story of introspection and self expression through art.

I am inspired.