Portfolio: Photographs

Letters from My Father

These photographs of my father, the late Willie Morris, and the letters he wrote to me are not, by themselves, related directly to one another. They came into being during the same twenty-five-year period, yet they do not necessarily occupy the same space. They do, however, represent an emotional roadmap of sorts. And when you put them together, they provide a new perspective on our lives and illuminate the complexities and dynamics of father–son relationships. It is an account of how a family communicates—or in some instances, does not communicate—with one another.

As with most of my father’s letters to me, there is nothing sensational here: there are no surprises, no dark secrets, no hidden family tragedies or secret affairs. A muckraking student journalist at the University of Texas, he had spent four years in Oxford, England, as a Rhodes scholar. Returning to the United States with a family in 1960, he became a crusading editor at the Texas Observer. Several years later, we moved to New York City and he became the youngest editor of Harper’s magazine, the oldest and most prestigious literary magazine in the country. His four-year tenure at the magazine is still looked upon by many as one of the richest and most productive in its history. After my parents divorced and he left Harper’s, he moved to the eastern end of Long Island. Within a few years, he began to write me letters.

In contemporary American society, the art of letter writing has been largely replaced by email and text messaging. No one seems to write very much for pleasure or for the simple purpose of staying connected. My father not only enjoyed writing letters, he was more comfortable communicating through them. He was from a generation of American men who were not quite yet able to openly express emotions. Born in 1934, he came of age during World War II and the 1950s, and grew up in an environment that certainly did not encourage men to be vulnerable. Emotions were seen as a weakness. And while my father developed the remarkable ability to express himself as a writer, like many men of his generation, he had great difficulties throughout his life expressing his emotions directly, especially when it came to love, affection, and anger.

But his letters to me are gentle and kind and offered a love that he might have found difficult to express otherwise. The letters were mostly handwritten in a simple, appealing script. They usually contain some advice, some form of humor, and always conclude by telling me how many friends I had, how much he missed me, and how much he loved me. These are emotions he was rarely able to articulate to me directly until much later in his life. In retrospect they were tender and nonthreatening, but at the time, I did not always see them this way. The man of the letters was not always the same I knew in person. The different sides of his personality often confused me.

My father took great pleasure in social interaction, and his habits occasionally came at the expense of those closest to him. Though he was by no means a bad parent, he was not always a very good role model. For most of his life, he kept very peculiar hours, didn’t cook or clean, and never answered the phone unless the phone’s number of rings matched a secret code. When I was in college he encouraged me to call him late at night at his favorite bars; I knew all the bartenders, so even if he wasn’t there, they might have seen him earlier in the evening and had an idea where he was heading. At least I could leave a message. When I would visit him in Oxford, Mississippi, in the early 1980s, we would go out to dinner every night, stay out until the bars closed, and often return to his house on Faculty Row with an assortment of students, poets, and barflies.

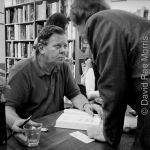

Perhaps by complete coincidence, I began to photograph my father at the same time he began to write me letters. As an aspiring photographer, I often responded to his idiosyncrasies by using the camera as a visual journal, but also as a form of protection—a buffer through which I could capture what I was feeling. As a young man in my early twenties, I was trying to establish my own independence and the camera became a way of setting new boundaries. Sometimes, I photographed him during his late-night sessions with friends, however, more often than not, I photographed him simply because I had my camera with me and he made for a good subject. He would take his beloved black Lab Pete and me for long drives in the country or for walks through woods behind William Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak. Or he would watch Ole Miss football with his buddies down at Shine Morgan’s on the courthouse square. Looking back through old rolls of black-and-white film I might find a whole roll of badly overexposed cemetery-scapes with one frame of my father. That one frame would be a gem, but often I had no idea why I took it.

As I reread these letters today, I feel grateful that he took the time to write them. As I edit through hundreds of images I made of him over a thirty-year period, I can still hear his voice and feel his passion for life and his love for humanity. This project, then, represents the growth and evolution of a lifelong relationship between a father and a son. The letters are more than mere correspondence in the same way that the photographs are more than just snapshots. No spoken dialogue survives, no recordings of disagreements or lofty praise. Instead, these separate elements become windows into the heart of our own separate realities. They span the vast spectrum of emotions and generational differences and are at the same time conscious of the undeniable affection, love, and mutual respect we always held for one another.

Select Letters

[Washington Star stationery]

[Washington, D.C.]

Saturday [early 1976]

Dear Dave,

I really like it here on the Star—some very nice people and a relaxed atmosphere. I do my first piece this weekend. I think I’m taking a tiny house (about nine feet wide, you won’t believe it) in old Alexandria. Much of Alexandria has been restored to what it was in colonial days, and you’re going to like the atmosphere. But it’s the tiniest house you ever saw. . . .

I sit in a huge city room with a bunch of wild characters, like something out of a Hollywood movie about big-city newspapers.

I hope you’re working hard on the books. I’ve told you before, you can do anything you want to if you just set your mind to it. You’re a lot more intelligent and imaginative than I was at your age; in fact, a lot of times I think you’re smarter than I am right now. What you need is more discipline in your work, the same kind of discipline you’ve applied to photography. You’re going to get into a good college; I’d just like for you to have as wide a range of choices as possible.

I’ll talk to you on the phone next week. I don’t know my home number yet. Yoder and Winston Groom send their best.

Love, Daddy

[For three months in early 1976, my father was a guest columnist for the Washington Star]

The Bridge

February 15, 1979

Dear ol’ Dave

. . . It’s been bitter cold here, about the coldest weather I’ve ever known in my life. I’m deeply into Taps. I hope it will be the finest thing I’ve ever done—it’s about growing up, about one’s first encounter with death and love, and the beauty of the Lord’s earth, with a story line that encompasses a good deal of what I’ve learned about the complexity of being human. It’s closer to the controlled emotions of the Great Gatsby, say, than it is to The Bear or Look Homeward, Angel, or at least I think so, and at any rate I don’t think you’ll be ashamed of me for this.

We miss you very much here, and are immensely proud of you for the hard work you’re doing in college. All of your many, many friends believe in your courage and talent, and I don’t say this lightly. You have a kind and beautiful way with your fellow human beings which undergirds your talent and will hold you forever in good stead no matter what you choose to do. I hear these things about you all over this town from the black Reverend Williams to Joe Valin to Jack Whittaker to Billy DePetris, etc., so never lose this rare, perceptive kindness you have with people.

I do hope we’ll collaborate on those two books—“The Sounds and the Silences” and “Mississippi.” However, if we don’t, and if anything ever happens to me, I hope you can find that spot in the Raymond Cemetery where all our people are buried—where we buried good old Mamie that day. Raymond is ten miles from Jackson, and your great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents and aunts and uncles are buried, largely in unmarked graves, not far from the picket fence with the Confederate dead. Some day many years from now you’ll be passing through that place with someone you love and will want to put a flower there, and take a photograph.

But that is many years from now, and in the meantime this is merely a note to tell you I love and miss your funny friendship. And try to read as many great books of literature and history that you can.

The snow is falling again, and why not?

Your friend, Daddy

[University, MS]

May 18, 1982

Dear Dave,

I’ve tried to phone you two or three times, to no avail. Well, I was so busy the final semester at the University of Texas, I wouldn’t have returned a call from Winston Churchill.

I wanted to know the exact date of your graduation so I could send you a graduation present which I have in mind—preliminary to the camera you want. Actually, “Pete” picked it out. I’ll try you on the phone again. Otherwise phone me.

I’m very proud of you. It seems like yesterday morning that we had breakfast at “The Triple Crown” (then called “The Village”) and you got into “the Golden Toad” and took the three ferries to the mainland. I’d lost my centerfielder, of course. Somewhere in one of my boxes I have your first letter to me from Hampshire: “Dear Daddy . . . I like this place.”

As I said on the phone, I’d like to be with you at your graduation. But your mom will be there giving the commencement speech, and quite frankly I’m very proud of both of you for that. The family will be represented there, and unless you phone me and want me to come too, I’ll just wait and give you a fine graduation party at Bobby Van’s this autumn with your best friends. If you wanted me up in Amherst for the graduation, all you’d have to do would be tell me, and I’d come. You know that.

I’m enclosing a check for you to buy some champagne and Moosehead for the graduation, and to take your mom and three or four friends to dinner on one of the evenings. I’ll certainly be thinking of you.

If there’s anything I can do to help after graduation, let me know—I mean in the way of advice on jobs and/or money. You say you’ll stay in the Berkshires this summer. I’ll be in “The Bridge” this fall, so we can get together and check signals. I’ll help you in any way. I’m enclosing a review from the Texas Observer this week of Terrains of the Heart, which may interest you, especially Mamie’s funeral, read it. It’s all just about places. Ronnie’s book on LBJ is just out and I’ve talked with him on the phone. . . .

Larry and Dean, and the Chairman, and Cornelia and Charles, and Patty and William want to send you graduation presents. I’ve told them to wait til you’re here. . . . Pete got terribly sick last week, a bad infection, but Dr. Shivers cured the good old fellow with antibiotics. . . . I’ll be in Washington D.C., next Monday for two days, then back home—dinner with many old friends, including “Dollar Bill” Bradley.

So—just a word to congratulate you on graduation, and to remind you I love you, and to call on me if I can help in any way.

Daddy

p.s. I’m working on Marcus, of course.

[I graduated from Hampshire College in Amherst, MA, in May 1982. My mother was the commencement speaker.]

[University, MS]

11/9/84

My Dear Dave,

It’s none of my business, but I get the impression you’re working too hard.

At your age, I worked my heart out. When I was married to your mother, I once went to a doctor in Austin because I was so exhausted in putting out the Texas Observer at age 26. I think he told me to stop drinking so many Coca-Colas and coffee and to seek a psychiatrist, neither of which I did.

I’d say, take it a little easier. I won’t say have an occasional beer (since both of your parents are hard drinkers) but to not drive yourself so much. Give a party at your house. Make spaghetti. Get a girl. Work slowly on “Highway 61,” for this is your baby.

Also, you should come see us in Oxford. Oxford is only 2 1/2 hours away, and there are a good number of people who really love you. You can have Thanksgiving here among close friends, and Christmas, if you wish. However, if you’re short of cash, I’ll certainly help you on a plane ticket to Austin for Thanksgiving, or to Washington for Christmas. At either holiday, go where you wish. Your Mom will surely want you with her at one or the other. You’ve been working hard, and the [Delta-Democrat Times] should give you some days off at both holidays, or at least one. . . .

It’s a curious relationship, father and son, and I do want to help you in any way I can. Unless I write a big best-seller in the next few years (which I may do) I’d like you to set up a special savings or investment account in Greenville where I can give to it a certain portion of my earnings as a writer. Henceforward, I’d like to put 20 or 30% of what I earn into this account for you. This won’t be much of an inheritance, but it’s the best I can do right now, or probably ever. I enclose a preliminary check for this account now. If I get more money, I’ll give you more. You might wish to consult [an] advisor as to how to best invest or deposit the money I’ll give you for this account. I’m not much of a businessman, but I’d put what I send you into an account which you can’t touch for a while. I’ve applied for a Guggenheim to write my novel Taps, which I may or may not get ($20,000). It’s strange being a writer in America—sometimes you hit it big, and I may do so. Anyway, take this enclosed check and start an account for you. Promise? One that you can’t touch for a few years? I’ll try to feed more into it, as I get it.

Sorry for the length of this letter. I love you and am proud of you . . .

Daddy

[After working for a year at the Scott County Times, I went to work as a staff photographer at the Delta-Democrat Times in Greenville, MS, in July 1984.]

Bogue Chitto River 3/12/89—75 degrees

Dear Dave,

I’m getting this in the P.O. to you in the hopes you receive it before you and Dietzel head south toward home. “Mississippi Burning” and “Dr. Jane” really touched me. You’re smarter than I am, you know, and I never took a photograph except with an old Kodak those many years ago, beginning in the Yazoo cemetery. And you’re a great writer. Your sensibility is of the heart—kind, bemused, tender, and brilliant. I can’t tell you of my pride and gratification in your courage and talent. Vern read the two pieces out loud. We shed a few Mississippi tears. Wow!

Love,

Daddy

p.s. Of course you can’t take the Delta out of the boy—it’s in your blood. Major Harper would be proud. Reading your piece, now I want to finish Taps on a strong note—for our progeny. This is important to me. Thanks for being my son.

[In the winter of 1989, my father moved into a cabin on the Bogue Chitto River outside McComb to finish Taps. I had already contributed several pieces to the student paper at the University of Minnesota, the Minnesota Daily.]

Jackson

4/18/97

Dearest Susanne and Dave Rae,

Charlie’s burial was one of the touching moments of my life. I’ve always been one to shed tears, unlike both of yours today, until later, and they’re coming now. Thank you both for being there with me, as you always are, and forever will be.

Thornton Wilder once wrote that we should owe the dead, not grief, but gratitude—and I believe that so poignantly true of Charlie, for we owe him so much. Grief is hard, but the gratitude assuages it a little.

“Fish” cried on my shoulder today and said, “We should all sing ‘Darkness on the Delta.’” Charlie was both expression and [a] creature of the tragic, crazy Delta earth—know it in his indwelling soul and played his sax and sang about it. I think that’s his legacy, and the friendships and loves that went with all of it. . . .

Herewith a check for Galatoire’s for two, maybe Monday or Tuesday before Celia arrives. Ask for Gilberto the Peruvian, not Gilberto the Cajun, but I think you know that.

Thank you.

Love,

Willie (Daddy)

[Charlie Jacobs was a saxophone player from the Mississippi Delta. He was a founding member of The Tangents in the 1980s. He died in New Orleans in April 1997 at the age of thirty-nine.]

Text and photographs © by David Rae Morris. All letters © David Rae Morris and JoAnne Prichard Morris. All Rights Reserved. Neither the text, letters, or photographs may be reproduced in any form without written consent.

David Rae,

I wont sleep tonight. My mind is filled with your Dad’s words and images. Thank you so much for sharing.

Love, family and friends, the great treasures of life. I feel like a billionaire.

Gay Reynolds, forever fan of Willie Morris

Dear David Rae:

It is always sweet to read his words. I must say that your words are just as sweet. I can show you that spot in the Raymond Cemetery where your people are buried.

A few years ago, Pattie Snowball and I were working in the cemetery and recognized that George Harper’s stone was designed to be a vertical monument rather than a horizontal one. Thinking it had fallen as so many others had, we prepared to reset it. Imagine our surprise when we peeked under it! Do you remember what is written there? Never fear though, we put the stone back exactly as it was found. I have a copy of the talk your Dad gave at the Raymond Cemetery the day you dedicated the marker to Major Harper, May 9, 1987.

Incidentally, or maybe not so incidentally, the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Raymond is May 12, 2013.

Thank you for posting the letters and photographs.

Isla

Splendid, photos and words, David Rae, or as your daddy would say, “ineffable.”

God, we miss him.

Hey David,

How very touching to read these very personal letters and the photos aswell. I like the photo of Willie with the funny hat on and the photo of him smiling I don’t know if I ever saw him smile.I don’t know what it is but I feel compelled to figure him out through his writing. I guess I knew him in a time of his life when he was perhaps a bit lost. I was just a kid and he was always nice to me but never seemed happy.After reading My Cat Spit Mcgee I feel happy for him. I feel he got to relax and be a part of a family again . I hope he was happy. I only knew him in Oxford and I get the impression he was pretty lonely there. My heart goes out to him and you thanks for sharing these moments.I am finally reading his other books one at a time trying to piece him together. I found the picture of me and Pete I was about 10 yrs old I will show it to you sometime.

Sincerely, Catherine Arnold

Thanks for these, David Rae. Something about pictures of Willie with a dog are especially transcendent. Also enjoyed reading those letters written to Hampshire College- and thinking of you through another lens. Hard to believe we are now the age he was then. Gee, I only send email to my grown kids- it’s just not the same.Hugs-Patty

I remember long nights, just the two of us in the theater at Hampshire pounding nails and running cables while we talked of our lives and aspirations. It’s hard for me to connect the image I had of your father painted from the indirect references and offhand comments from then, with the letters I read above.

It’s wonderful of you to have and share these letters. My father and I had a very open, warm and loving relationship, but I have no written record of it now that he is gone, (roughly as long ago as Willie) and he lives on only in my brother’s and my memories.

Whatever faults he may have had, you have a wonderful record of his love to keep and to pass on to Uma. What a beautiful legacy to pass on.

P.S. In whatever format, genre or medium works for you, you should be writing. Your prose is something I could read all day long.

Dear David Rae,

I am so glad to read all these wonderful words by you and by your father. Don’t know why it should come as any surprise that you are a writer, and a damn good one. (Maybe it’s because you are such a good photographer that I did not realize you also had also the gift of writing?) The letters your father wrote are a treasure — to you and to all of us. I found myself reading these with tears, especially reading his account of CJ’s funeral. He was right about that strange and talented (and self-destructive) “creature of the crazy, tragic Delta.” What an honor to have known him, and to have know your father, and to know you.

Your friend and fellow photographer (and I also claim literary groupie),

XXMaudie

All the typos above, please disregard. As JoAnne will tell you, I am not a very good editor!

David Rae,

What a joy to see you and catch up a little. I miss your daddy every day and to have you share his voice with us in such a lovely, personal way leaves me nostalgic for those warm and sometimes troubling days. And Uma is a fifth grader and my grandson is five! Wouldn’t Willie have loved that?

Much love my friend.

I am a brand new fan of your father’s…introduced to him by a fellow Yazoo City denizen who told me a sweet and funny story about him. I have read only two of his books, loved them, and look forward to reading all, or at least most, of his work. I also enjoyed reading this page and intend to look up your works as well. I lost my own Daddy in 1997 and cherish the one or two letters I have from him. How lucky are you to have so many? And his other work as well! Thank you for sharing these photos and the letters.

Elizabeth