Share Life, Share Death: Church, Inspiration, and the Art of William Walker

One of my first memories of kindness under the cloak of church came in the second grade. For some reason, still unknown to me, the church set me up in some kind of “partnering” system with an older member of the congregation. Her name was Katherine and she seemed extremely knowledgeable and rather glamourous to me back then. She lived on about nine acres of land adjacent to the church, in a house tucked back in the dense woods. The property was sold after her death and made into a gated community, but if I put my mind to it, I can still recall the allure of those dark and mysterious woods and the glow I felt when she turned her septuagenarian attention and wisdom my way. Though I realize in hindsight she was probably roped into mentorship by the servant call of the church, at the age of eight, it meant a lot.

The most dramatic moment in our relationship came when I quickly became ill one Sunday afternoon at a carnival set up on the church grounds. She was kindly shepherding me from one campy carnival game to another when my tummy felt suddenly uneasy and my face incredibly hot. My mother was summoned, and I almost made it to the car before losing my cotton candy, amid other savory carnival treats, all over the feet of angelic Katherine. I was mortified. She was gracious. I spent the next week or so under a mountain of quilts with a repurposed sand bucket beside my bed as some version of the flu leveled me. When I improved, Katherine came to visit. As the years passed, she remembered birthdays and milestones, and remained a steadfast friend as time passed. The resources she shared with me included gifts and other marks of material culture that so often dominate our sense of value, but as in any healthy community, the most meaningful resources were much more personal and ultimately invaluable. They included wisdom, grace, instruction, care, and inspiration. The latter of these, inspiration, is perhaps the most mysterious.

The word “inspire” means, in its most archaic sense, to “breathe into” or infuse life through breath. Webster’s more updated definition is “to influence, move, or guide by divine or supernatural inspiration” or “to exert an animating, enlivening, or exalting influence on.” The subject of inspiration is one that holds great value for me. As a writer who trafficked largely among other artists for years, I took the concept of inspiration for granted. It’s something you recognize intuitively, without much thought, like spotting a plate of delicious food on the kitchen counter when you walk in starving. But explaining how it works or what it calls us to do is much more difficult.

This question resides with me daily as I find myself engaged in a long-term project that seeks to stoke a sense of inspiration in churches yearning to build authentic connections to people in their twenty-something decade. In this project, churches work to understand their DNA from the inside out, while at the same time utilizing their creativity to grow in new directions that consider the needs of people under thirty. It’s what I like to call “a doozie.” We are constantly discussing subjects like inspiration and creativity on a molecular level, sometimes enlisting the expertise of “creatives,” but I often have the nagging sense that perhaps we don’t have to look that far for a better or deeper understanding.

It was during one of these frenzied work weeks that I received a card in the mail from my mother that would slowly bring this intuition into focus. To clarify, my mother is one of “those mothers.” Deeply caring, a little crazy, and always providing ample fodder for conversation, a knee-slapping story or two, and lots of good-natured puzzlement to and for those who love her. She’s prone to writing me novel-length letters on index cards and sending me thoughts, memories, or ideas noted during a sermon, which she records in a rectangular fashion, circling the church bulletin until she runs out of room and writes the last sentence on a prayer card. She once sent my children an empty milk carton and those tiny communion juice cups in a package for which she paid good money to post, and it would have driven me crazy if it hadn’t become their favorite toy.

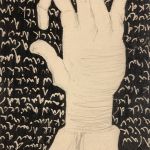

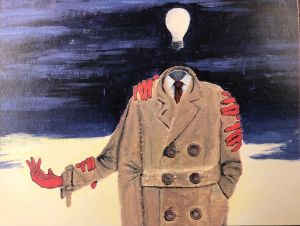

This is all to say that mail from my mother can unleash and illicit all sorts of reactions, from exasperation to prolonged entertainment. For weeks this fall I received cards from her attributed to an artist named William Plaxco Walker, and I assumed she picked them up at a wayward Southern museum or art market. They had the resonance of great folk art: real, bold, visceral, with a tiny bit of magic to boot. I loved the cards, propping one up on my bathroom counter and another in the kitchen. Then one week, feeling knee deep in all these church conundrums, she sent me one that took my breath away. This is it, I thought to myself, this is how inspiration really feels. The lightbulb, the sense of Divine guiding that is at once comforting and disconcerting. The next time I spoke to my mother I asked her where she got the cards and what she knew about the artist. “Oh William Walker!” she responded. “You are right. He was so talented.”

To hear my parents say his name brought back some resonance of memory, and my mind fixed on the “was.” William Plaxco Walker was a beloved member of my parents’ church, a well-loved young person and an immensely talented artist. He was also diagnosed with a rare type of bone cancer at the age of twelve, and after many years of ultimately unsuccessful treatment, he died in 2005 at the age of seventeen. I tried to find a record of his work online, but all I found was a brief but poignant obituary:

William was an eleventh-grade student at Randolph School and was a member of Covenant Presbyterian Church. William was surrounded by the best friends a man could ask for.

It was short, but said so much. To grasp the expanse of his story, staring at his illuminated work, did a number on my heart.

To hear my parents tell it, his death was part of a much larger story, one that included the inspired and inspiring work that his parents do in and through the light of his memory. By their account, his mother is devoted to the young people of the church, and the cards they sent me were one of the ways the church strives to celebrate and keep William’s memory alive. William’s art shares much of his story, and the narrative I read as inspiration in his work also embodied the mystery of suffering. In many ways, inspiration and suffering often feel like two sides of the same coin. Both are an essential part of beauty. And in the true nature of congregational life, he shared these resources, and in portioning, the burden grew lighter and the plenty was amplified. In sharing, the story continues.

William played his part in that story, faithfully and with such beauty and brilliance. His legacy calls us to live into that. What do we have that either requires or feels worth sharing? This is the essence of congregational life, and I would argue of any community that is worth being part of. I feel gratitude toward William and the way his work illuminates both the concept of inspiration, literally the breath of life, and the way that inspiration takes up residence in and among healthy communities. Much is given, and in giving, much is gained. The fount of every blessing, as the old hymn goes, with streams of mercy that never cease.

My own mother’s ecclesial flow is still in full swing, and in a recent letter she said that she and my father were interviewed for Senior Sunday at their church. When asked about her favorite memories of the church, she answered that some of her best memories were praying together with people, and that those people have become her best friends. The thing I’m relearning with churches these days is that time is always our most precious resource, and if we find ways to encourage younger generations to share it with each other generously, preferably through activities that invite vulnerability, it might just be the salve for the pandemic of loneliness that is sweeping the country right now. In William Walker’s story, and in his work, we find a new kind of iconography in which we all can share. Not the suffering of a distant saint, but of a young person who resolves himself to be fully human, sharing the resources of both his talent and his remarkable passage with all those willing to travel with him, inviting others to become, through that journey, “the best friends a man could ask for.”

*All artwork by William Plaxco Walker

A wonderful story from my dearest student and friend. Your Mom has been coming to yoga and she is so loved by all in the class . Know that you are loved and that I am so very proud of the individual, daughter and mother you are. Miss you.

Martha Lynn, I loved your article. It was so uplifting at a time when we read so much that is negative.

Thank you for taking the time to put your thoughts on paper, especially when u have so little free time.

Beautifully written for an amazing spirit.

Martha Lynn, thank you for pulling up all the wonderful memories that Katherine left Ys. She is the reason I am a teacher. Sweet William was such an inspiration to all who knew him. Thanks for tying them together in such a beautiful way.

Martha Lynn, thanks for this beautiful writing. I was truly blessed to be raised Katherine, whom we called Kakai. She was truly a Saint that I miss every day. I know she touched so many lives in many ways. Thank you!

Thank you for such a heartfelt account of a fine young man and his amazing family.

Wow. This is a wonderful tribute article to William and his family, as well as a call to each of us to be human fully with each other, in the presence of God. Funny how we “livie life forward to only understand it backwards”.

Thank you for sharing. Brings back many many great memories of Katherine and William. I have received letters from your mom that I treasure! She is truly one of a kind.

Thank you for a beautiful story about a strong William Walker.