Summer in the Broken Home

I cannot believe I’m crying over my house.

My house!

When I lived there, it had a roof. It had windows.

In May, a tornado blew through Jefferson City, Missouri. The roof on my house flew the coop. The windows sharded the ground. A column no longer touched the pediment above, and the porch crashed. I saw the damaged house in pictures on Facebook. Six weeks later, I saw it in person.

My hometown is Missouri’s capital, purposefully located halfway between St. Louis and Kansas City. The tornado didn’t start wreaking its havoc until east of the capitol and the governor’s mansion. Capitol Avenue, which runs smack into the capitol building, is a stage setting for nineteenth-century McMansions. Some were built by convicts for the heads of industries doing business in the state penitentiary on State Street. Many of those houses were finally being restored before the storm; many were destroyed.

A block below Capitol runs High Street, “high” a misnomer in geography and architecture. Commercial buildings vied with rooming houses, none significant or even interesting.

The 500 block of East High did not hold a row of Malvina Reynolds’s “little boxes”—no two were alike. On our side of the street sat a blond-brick apartment building; on the end, stood a couple of red-brick rental properties next door to the four-columned Sugarbaker Tumor Clinic. The late poet Deborah Digges, one of ten Sugarbakers, included tales of working in her father’s clinic in her memoir, Fugitive Spring. I devoured that brilliant book, keenly aware that her childhood memories differed significantly from mine though they were formed just a few buildings apart.

The Sugarbaker Tumor Clinic (left), the Medical Arts Building (middle) and the building with our flat (far right) in the 1960s.

I grew up at 527 East High Street, five blocks east of the capitol, three blocks south of the Missouri River. This river was not made for swimming or boating, just commerce and cholera, mosquitos and mud, and Lewis and Clark. When I grew up, the river and the capitol were always there. The first sight of them as I sail across the bridge still means I’m home—even though I haven’t lived in Jefferson City since I graduated from high school.

Friends from the Class of ’64 posted pictures on Facebook within minutes of the tornado’s strike. I studied the wreckage through a veil of stupid tears. Tennyson’s, the furniture store across the street from my house, had been smashed to smithereens. Mrs. Tribble’s house suffered less damage, but my house, next door, appeared to be a goner.

The house, built in 1910, never rated a label like “Queen Anne” or “Prairie Style.” Granted, its bay window stuck out pleasantly on the front, cordoned by a pretty-enough porch, painted sky blue and reached via a dozen wooden steps, mandated by Jefferson City’s hills. The main front door opened to a vestibule that opened to two apartments, one downstairs and one up.

What we called our house was really the first-floor apartment, two bedrooms and one bath for five females—my mother, my sisters, and I. Mother and Daddy had taken up residence in 1949 when Daddy found a job reporting for the News & Tribune and Mother as a Linotype operator for a local press. I was almost three and my older sister Carole was nearly four when we moved in. Two years later came Mary; five years later, Ellen. The D-I-V-O-R-C-E came in ’59—he moved into his girlfriend’s house on West High, leaving us on East High with downtown sandwiched between.

We went to town by “shank’s mare,” Mother’s expression. We didn’t have a car in the fifties and sixties. Well, we had one, but the Pater took the Oldsmobile and left Mater with the payments when he went off with his doxy. Woolworth’s, Kress’s, and J.C. Penney’s passed for department stores. Woolworth’s sold parakeets and tiny turtles in the back, the closest Jefferson City got to a zoo.

Mother had rules about going to town. No shouting to greet the other children across the street. Even in summer, no shorts or slacks and definitely no blue jeans—just like at school. “Be a lady if it takes a leg” was another of Mother’s expressions, this one inherited from her father.

When I read Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings, I delighted in her description of leaving her petticoat on her bicycle to be ready whenever she needed to make a book run to the library. I loved that she had to wear a dress, too—and had to be sure no one could see through it—to go to downtown Jackson, Mississippi. I didn’t have a bike. The folks said I could have one when I kept my room clean. Took me a while to register that I didn’t have a room and that they didn’t have any money.

Occasionally, we sweated all the way to the capitol to tour the museum in the undercroft. Mary and I would take off our sandals to walk barefoot on the cool marble floors. We skated around the stage coach, stared at the stuffed river otter, or idly flipped the giant, squeaky panels holding photographs of governors.

On the way home from town, we usually stopped at the library. One of Andrew Carnegie’s little gifts perched across from the A&P, accessible either by High Street with a jog at Adams, or straight through the alley behind our house. To gain the alley, we took the shortcut through Mrs. Tribble’s steep backyard (we didn’t even think that we were trespassing, and that blessed woman never, ever complained).

I filled my arms with library books, balanced with my chin and juggled with a bag of bread or a pack of Raleigh’s for Mother from the grocery store. I lumbered home through the heat, carrying Frank Slaughter, Elizabeth Taylor, and Florence Barclay; Daddy Long-Legs, State Fair, and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. I read books not knowing they’d been made into movies since we couldn’t afford the Capitol Theater; Mother even put the kibosh on Lady and the Tramp, basing her censorship on the suggestive title alone.

Mother and Daddy read all the time, too, their shelves filled with Book-of-the-Month Club selections, and with Ernie Pyle, Winston Churchill, and the Brontës with Fritz Eichenberg’s chilling engravings. I read and re-read Jane Eyre, deeply, profoundly grateful to have found a heroine I could identify with, a girl who was also blamed for things she did not do, a woman with integrity.

Living that close to town, we had no neighbor kids to play with. Also, being from a broken home, back when people thought divorce was contagious, we were off limits to classmates as playmates.

Only grown-ups lived next door. Mrs. Tribble rented her upstairs rooms to “girls,” women who worked in the state offices. Next door to her, the house had become a doctor’s office. Next to that was a warren of doctor’s offices. The grandly named Medical Arts Building had usurped the grand house with the wrap-around porch that had presided over the middle of the block when we’d moved in. Its parking lot, terraced to accommodate a hill, tested our summer feet. It usually took about a week for Carole and me to walk barefoot on those searing stones without ouching, but then we were good for the whole summer.

That parking lot also tested our prowess on roller skates, the kind with the key that tightened the skate onto our shoes, sorta. Carole and I would tromp up to the second level of the parking lot and let ’er rip down the steep driveway, grabbing ahold of the telephone pole, hopefully before splatting on High Street. We whirled around that pole like fast little strippers.

That was about as exciting as our summers got.

During school, Carole and I often met Mother in the afternoon as she got on the same bus to go to work that we got off of from school. She handed us the chore list in passing: dusting, sweeping (including teasing bobby pins out of the dust bunnies), and scouring the tub. Always on the list: washing dishes that had piled up over arguments: “It’s your turn.” “Nuh-huh-uh!” Unwritten but expected was caring for the little sisters—feeding them supper, getting them ready for bed, monitoring their homework. I folded rectangles of birds’ eye cotton into triangles of diapers for Ellen and quizzed Mary on her spelling words while my equations waited to be solved; my sentences, to be diagrammed.

During summer, days drawled by without that break at 3:30. In the early mornings, I sneaked in a few chapters of my book in the blissful quiet. I lay on the davenport, my back to the living room and my head on my pillow, propped up on the arm pocked black by cigarette burns. From my nest, I wandered into other eras (When Knighthood Was in Flower) and worlds (Girl of the Limberlost).

When Mother awakened, she groggily hung off the side of her bed, cigarette stuck between her lips, ordering me to heat her coffee from last night’s Thermos. The girls were still asleep, so I’d tiptoe through their back bedroom, its windows darkly mirroring the windows two feet away from the last house on the block. In the kitchen, morning light streamed in, diluted by a giant fan in the only window. I liked that morning light because, in the night, when I turned on the ceiling light in the kitchen, I had to wait at the door for water bugs the size of Chevys to skitter across the linoleum. The night kitchen was no place to be barefoot. Mother always blamed living close to the river for those big black bugs, like lousy housekeeping was not a factor.

That window fan, Cooling Plan A, conditioned the air on summer nights. It blew warm wind over me when I slept in Mother’s bed next to the west window. Mrs. Tribble’s house sat two feet away, so close that we could secure our hands and feet on each house and monkey up the walls. Cooling Plan B: plop my chicken-feather pillow on the floor. Wait a few minutes. Lay my sweaty head on the cooled pillow case. Fifteen sleepless minutes later, repeat.

Summer mornings were for chores. Because Mother worked, we did not follow the dictates of dishtowels to wash on Monday and iron on Tuesday. Saturday was wash day at our house. I loved hanging clothes. Oh, the order I could bring out of chaos by sorting wet globs of laundry. Shirts with shirts, sheets with sheets. Sheets had to drape over the lines, which were over my head, so serious flinging was involved. Underpants pinned by their elastic, dresses at the shoulders, blouses by their tails. Handkerchiefs and diapers flapped with determination, married at the corners by a single clothespin, so martial and precise.

Theologian Barbara Brown Taylor understands the appeal of this sight to me—still my favorite image: “Hanging laundry on the line offers you a chance to fly prayer flags disguised as bath towels and underwear.” Amen.

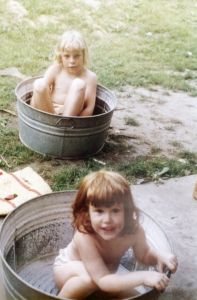

We sunbathed in the little backyard. Wash tubs, left out all summer, yellowed the green weeds that passed for a lawn. Tubs, girls, books—and squirts from Ellen’s baby oil to speed tanning. However, after going to the trouble of filling a metal tub with water from the hose (and taking a yucky drink or two), I managed only the briefest time in the sun. The rays blinded me, reflecting against the white pages of my book, and heat made my pulse pound, drowning out the words in my head from my “beach” reading—Parrish or Sue Barton: Student Nurse. Back inside to the daveno for me.

We went nowhere in the summer. Not like our school chums with cabins at the Lake of the Ozarks and cars to drive there. Not to the big city or a park. As a little girl, I read a book about a family trying to decide whether to vacation at the ocean or in the mountains. It made no sense to me whatsoever. Oceans? Mountains? If we mined money from the sofa cushions, we might manage a week in July at the local Girl Scout day camp. We braided plastic lashes into lanyards and set up housekeeping in dirt spaces laced by limbs. Camping never made much sense to me, either.

If our folks went on a summer vacation, we were parked with one or the other of our grandparents. Our paternal grandparents lived in St. Louis. Visiting meant Calvary Baptist Church with Sunday School and worship on Sunday morning. Daddy passed sen-sens to Carole and me to shut us up. Blecch. I hated licorice. Sunday evening: Training Union and worship; Wednesdays: Sunbeams for children, prayer meetings for grown-ups; Thursdays: visitations to Sunday’s visitors or absentees. Not the zoo or the botanical garden or the art museum. Church.

Our maternal grandparents lived in Sullivan, Missouri, much smaller than Jefferson City. Granddaddy published the Tri-County News, so our visits appeared on the front page as reported by Grandmother. Mother learned to run a Linotype at that newspaper, where Daddy worked before they married in 1941 and until they moved.

Grandmother took us fishing (boring, bugs). She knew the good places to pick berries and didn’t mind bloodying her bare arms (I did). She took us swimming in the Meramec River (I didn’t know how to swim, the current terrified me, and the rocks on the bottom hurt my feet). Grandmother monitored my embroidering; I’m still grateful for her patience and her standards, insisting that the back of the dishtowel look as good as the front. She taught us penmanship, guiding circles and slants, over and over between lines, sweat dripping off our hands.

I happily read through blistering hot afternoons, transported to Tara in Gone with the Wind from her screened-in porch. Carole read to Ellen under the bank of spireas. Mary ate up the Nancy Drews Grandmother gave her, her very own precious books that she didn’t have to take back to the library, ever. Grandmother, when she finished canning or making jam or mending, read the latest Saul Bellow.

The year Granddaddy bought a television, long before our Crosley arrived, we couldn’t wait to go to Sullivan. TV! We did not reckon on two disturbances: 1. Their house sat by the railroad tracks. Engines, as loud as tornados, roared through the evening’s programs. 2. The Democratic convention, the summer of 1952. We sat glued to the TV box watching Adlai Stevenson. His portrait hung on our living room wall along with Roosevelt’s, Truman’s, and Alben Barkley’s. We were Democrats, three generations strong, but Stevenson was no Lash LaRue.

Mostly, though, we stayed home in Jefferson City, Missouri, through the summers. Mrs. Tribble’s mimosa draped over our yard, and we danced its pink blossoms like tutus on coked-up ballerinas. We made clover chains. We lolled on the front porch on wavy wooden steps or in ratty wicker chairs. We counted cars as they drove past Tennyson’s or arrived for a funeral at Dulle’s parlor across the side street. From that front porch, we watched the merriest parades after weddings—cars honked, brides waved in froths of white, and cans tied by groomsmen to the bumpers clattered along High Street.

Otherwise, summer vacation offered little but hot monotony to us ragamuffins. Summer holidays meant less. We did not celebrate Memorial Day except to cheer that school was out; we did not celebrate Labor Day except to bemoan that school was in. The Fourth of July meant—at most—waving a few sparklers in the front yard.

On the Fourth of July 2019, six weeks after the rip-snorter tornado, three sisters drove through Jefferson City en route to visit the fourth. Having seen the saddening images on Facebook for days, I knew what to expect when we cruised through town. Our junior high school building boarded up, probably never to re-open. Houses with one side eviscerated, leaving the other three façades oddly intact. Quasi-majestic houses reduced to splinters; the Doric columns on Dr. Sugarbaker’s clinic, just firewood. The Medical Arts Building’s window jams had been filled by plywood that was painted with “Caution: Falling Glass.” On Mrs. Tribble’s house, authorities had plastered a green sign for “salvageable.”

On ours, the sign on the etched front door was red.

Our house, not much to begin with, had been routed to an ignoble end, 100 years of serving the renting poor, over in minutes. We had come from a broken home, and now it was truly rent asunder, its roof blown off, its windows blown out, and that column on the porch refused to stand up straight. As we drove past this summer, one more tear fell down my face. It was never a great house, but it was home, and, now, it is gone.