The Bounty of Dirt

Last summer, a friend placed a worn wooden bowl and a platter of fresh sliced watermelon and peaches on the table. I remembered thinking that the sound of those particular words, “bowl” and “platter” represented a world of fullness and bounty. The weathered quality of the wooden bowl was reminiscent of the frame of the lovely old beach house I shared with a group that week. Like me, like all of us, this old house had weathered more than its share of storms, but like us, and the old brown bowl, it had also cradled bounty.

It was the peaches, with their fragrance and their perfect plump slices, chilled just a little, that reminded me of home. Not what I think of as home now, the nests I have created with my children, but rather the small South Carolina hometown I grew up in, where everyone harvested peaches in the summertime, and still do.

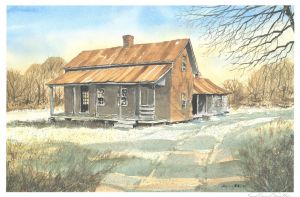

That fragrance of peach juice is also associated in my memory with watermelon still warm from our field, and the old, wood-handled butcher knife that carved the large oblong melon in half and then in halves again and then in smaller sections that fit into a child’s two hands. Watermelon became party food as we chased each other around the expansive yard underneath the shade of fifty-year-old pecan trees, spitting the seeds at each other, laughing like a bunch of hooligans. Rather than take us into The Shack, the rickety tar-papered shelter we called a house—where we would only add the red stickiness of more dust to a place so open to the elements at all times of the year that it could never really be called clean—our mother draped a length of green hose over a large limb of the biggest pecan tree and turned on the water in the pump house. We took turns standing under the stream of our handmade shower, indulging in what current preschools would probably refer to as water play. The only indoor plumbing in The Shack was the cold water spigot in the kitchen. For us, frolicking in a cold water shower in the humidity of a South Carolina summer was a welcome change from a winter bath in a tin tub filled with water warmed on the stove.

My father, a hard man in the best of times, believed that farms were for growing food and other crops that sustained us. There was no place or time for flowers or the purely ornamental. So perhaps it was the previous tenants who planted the matching forsythia and daffodils by the front door that signaled the coming of spring, closely followed by summer in the Carolinas.

I loved Vacation Bible School at Union Baptist Church in Filbert, South Carolina. Although we attended church every time the doors were open the rest of the year, the summer was special. Vacation Bible School was about dressing lightly in sundresses and sandals and marching into the air-conditioned cool on thick blue carpeting, before going our separate ways to classes geared to our age group. Sure, there were Bible lessons, as usual, interspersed with the recreation, but there were also lots of arts and crafts and yummy snacks like vanilla sandwich cookies, bought in bulk, and Dixie cups of sugar-laden Kool-Aid that turned our lips and tongues red or green or purple.

The Bryant family also attended Union Baptist, so maybe that was why we always went to their large peach orchard on the by-pass, where the four of us children helped our mother pick a bushel at a time. The fresh fruit was so fuzzy it made my bare skin itch wherever it came in contact. It never occurred to me that others bought their peaches by the bushel while we picked our own for mom’s canning and freezing and peach cobbler. And it didn’t matter to us, or to our petite mama who hung all the laundry for our six-person family on a clothesline stretched from the house to a backyard light pole, that the juices ran down our faces, down our arms and onto our summer play clothes, already stained with the red clay of the farm.

***

My favorite playmate in the summertime was my cousin Linda, who came with her parents and siblings on occasion from Charlotte an hour away. Watching from the hill where The Shack stood, we could see the tornadoes of dust their car created on the dirt road a half mile away as they made their way to our house, where we watched and waited for their arrival. “Here they come!” one of us would shout to the others as we ran to greet our aunt and uncle and cousins.

Linda and I would immediately distance ourselves from “the little ones” and head down to the gulley, a gigantic ditch with steep sides 3-4 feet high, perhaps formed by river water, but then reduced to a small creek where tiny tadpoles swam. Immense trees shaded us there and a massive one had fallen across the gulley allowing us to risk injury in attempting to cross it without anything below but the accumulation of dead leaves from decades of autumns. Sometimes we played house, serving each other dirt patties on leaves, stirred with sticks. We picked honeysuckle blossoms and broke off stalks of sugar cane, sucking the sweetness from each.

In hindsight, we should have been afraid of snakes—black snakes and copperheads that attempted to nudge themselves through the broken screen of a shambling back door only to be shooed away with a shovel or hoe by a grownup, who never seemed to be frightened by the intruders. But outdoors, our hooting and hollering probably scared them away long before they could become a threat.

It was Linda, eighteen months older than me, who explained about the birds and the bees. One summer day when I was about ten, Linda and I were squatting behind the barn to pee, and she seized the moment to fill me in.

“You are lying,” I said, even though calling someone a liar was as big a sin as actually telling one in my family.

“Just you wait,” she said, offended that I did not acknowledge her superior knowledge in the matter. “I saw my mother give your mother The Book.” The Book—a thick pamphlet called Now You Are a Woman—unfortunately did make its debut in our house later that summer. Illustrated with black-and-white sketches of wombs and uteruses, but no mention of penises, it was truly a disappointment as books go—on so many levels.

On rarer occasions, we spent the night at my cousin’s house in the city. To me, the flush of a toilet was the sound that luxury made. Hearing it early in the morning when I was still half asleep, I would roll over in the bed I shared with Linda and sigh with contentment.

There was a milkman who delivered fresh dairy to the farm for a while after our cow Betsy quit giving milk. Getting to the grocery five miles away was difficult when my father was away as much as twenty-four hours at a time as a long haul trucker, taking with him our only car. The milkman was a friendly, thoughtful person who always asked our mother if it was okay to offer each of us a kid-sized carton of cold chocolate milk on a hot summer afternoon. She smiled almost shyly and thanked him graciously for his generosity to us but refused any for herself.

There were times, after a day filled with pulling corn or shelling peas or taking care of younger siblings that I just wanted quiet, alone time. Lying on my back in a field of tall, wild Queen Anne’s Lace, I could stare up at the blue of the country sky and no one but the dogs could find me. I was close enough still to hear the comforting murmurs of the little ones nearby but not so close that they could encroach on my separateness. Drowsy with both work and play, I would close my eyes for a few minutes, feeling the warmth of the sun freckle my face while a quiet breeze brushed the Queen Anne’s Lace against my legs. Once I broke off a big bunch to take to Mom to put in a Mason jar with water. She made magic by dropping a bit of food coloring in the water which seeped upward into the flowers, turning the lacy white to red or green or blue.

Later, much later, when I lived in Tokyo as an expatriate with my husband and two young daughters, I stopped at a flower kiosk on a busy corner of Roppongi (High Tech, High Touch Town). Tiny bunches of Queen Anne’s Lace were selling for 1,000 yen or the equivalent of $10. Homesick for the familiar, I bought them and took them home, remembering their smell and longing to lie on my back under a clear South Carolina sky. I saved one out of the bunch for my daughters, dropping a bit of food coloring in the water to make magic for them.

Though my parents had long been divorced by the time of her death, my father planted a red rose bush at the farm by the road in memory of her. It grew lush and wild through neglect until my father’s death, when my brother and his family took over that section of the farm. He replaced the already crumbling house that had taken the place of the shack of my remembrance with a modern house with hardwood floors and central air and more bathrooms than they probably ever use. My brother cut back the rose bush and tended it lovingly until it could no longer be saved.

Someone once asked me why I chose to return to the Carolinas after two decades away.

“It was the smell of the dirt,” I said, surprising even myself. “I missed the smell of South Carolina farm dirt. It doesn’t smell the same anywhere else in the world.”

And if I listen from the hill underneath the now hundred-year-old pecan trees that shade my brother’s new house, I can imagine that I can still hear my mother calling four children by name—ranged by birth order—home for supper.

***

My friend’s sliced peaches now make me think of what a gift that freedom of summer provided, never to be scolded for making a mess of our shorts and tops when only my mother knew how much effort she put into that one simple never-ending task of keeping four children within five years in clean clothes. That same generosity of heart and a profoundly practical nature allowed us to run barefoot with exuberant dogs and small playmates all summer long while snacking on watermelons, wild blackberries, and muscadine grapes that we picked ourselves.

In retrospect, I was surrounded by beauty and bounty in that place and time. I am ashamed now to recall that I once believed our family was poor.

Made me cry

Unbelievably beautiful! Loved loved loved this piece!

That last line, it says SO much about the narrator. This is gratitude at it’s best, the definition of abundance. The smell of dirt, peaches, it is all we need. Thank you my love!!!

What a wonderful story! I didn’t know your mother well but remember her as a gentle lady. Your mother was a remarkable woman & so is your piece.

I loved this piece! I could feel the love in your writing of a simpler time in the life of a child growing up in the south.

Made me laugh out loud and miss my summers in the South.

You took me to your home and life. Thank you for the beautiful story.