Gothic portal of Sultan Nasir Mohamed Mausoleum. Photo by M. Serageldin

Share This

Print This

Email This

The Cairo House: Prologue

Excerpted from The Cairo House. Audio recording by the author.

The Chameleon

For those who have more than one skin, there are places where the secret act of metamorphosis takes place, an imperceptible shading into a hint of a different gait, a softening or a crispening of an accent. For those whose past and present belong to different worlds, there are places and times that mark their passage from one to the other, a transitional limbo: like airports.

Watch the travelers going through the arrival gates for overseas flights: the Saudi woman in Western dress who lands at Jedda Airport and immediately fishes out a Hermès scarf to cover her head; or the Indian expatriate doctor, landing in Heathrow after a visit home to Delhi, shrugging off the warm memory of the clan’s adulation and emotion; re-adopting the clipped British accent for which his family paid dearly, and which they would now find pretentious; re-aligning his defenses as he passes under the sign marked Aliens.

Nor is this phenomenon limited to the expatriate and the globe-trotter. Watch the passengers arriving on the domestic flights, being greeted by family and friends, or by strangers holding up a sign with their company name. Watch the subtle shift to accommodate a change in status or expectations, as we play our many roles in life: boss and child, parent and lover, hometown hot-shot and small fish in a big city pond. We emerge from the tunnel ramp and swing through the gates, a chrysalis bursting free of its cocoon, Superman erupting from the telephone booth; or we shuffle off to the luggage carousel, waiting to pick up the familiar battered luggage with which we left.

But the true chameleons are the ones who straddle two worlds, segueing smoothly from one to the other, adjusting language and body language, calibrating the range of emotions displayed, treading the tightrope of mannerisms and mores. If it is done well, it can look deceptively effortless, but it is never without cost. There is no hypocrisy involved, only the universal imperative underlying good manners: to do the appropriate thing, to make those around you comfortable. For the chameleon, it is a matter of survival.

***

“Ladies and gentlemen, we will be landing at Cairo Airport in twenty minutes. Local time is 4 p.m., and the ground temperature is 22 degrees Celsius. Please fasten your seat belts and return seats and trays to their full upright position. We remind you to have your passports ready and your landing cards and customs declarations filled out. Please exercise extra caution when retrieving your carry-on luggage from the overhead compartment, as it may have shifted during the trip. We hope you have enjoyed your flight and thank you for flying with TWA.”

I stare at the landing card in front of me. “Purpose of visit: Business or pleasure?” Simplistic questions in a complicated world. What is the purpose of my visit? How do you answer, I have come back to claim what’s mine? To find out if it is still mine. To find two children I left behind when I ran away a decade ago: one child is my son and the other the girl I once was. The future and the past. Between them they hold the key to the question I have come to try to resolve: where do I belong? Where is this chameleon’s natural habitat?

I fasten my seat belt and smile at the white-haired couple next to me as they grasp each other’s knuckled hands. They are from Minneapolis, on a tour of “Egypt and The Promised Land.” They have shown me photographs of their grandchildren in their home at Christmas; in her kitchen she has Christmas tree china on which to serve lebkuchen, and in his workshop he has a mug inscribed “to the world’s best grandad.”

We have made small talk about cross-country skiing and hockey. At some point they ask me where I am from, and I answer, truthfully, that I live in New Hampshire. It is not evasiveness, nor even the instinct to resist being pigeon-holed. It is only that any answer I give will be just as incomplete and misleading, so this is as good- or bad- as any other. With Midwestern reserve, they do not persist. But I can tell that they feel rebuffed, and they settle back in their seats and turn their reading lights on.

I have not exchanged a word with my neighbor across the aisle, but I cannot help deducing, from her loud conversation in Arabic with her daughter, that she is on her way home to Cairo after a visit with relatives in the States. Their true mission, I suspect, was shopping. Perhaps the girl is engaged, and there is her trousseau to buy, and a long list of presents for relatives and friends. The two women have come on board with a quantity of brazenly oversized carry-on luggage. They are already rummaging around them and in the overhead compartment to collect their many belongings in preparation for landing. As soon as the wheels of the plane skim the ground, they will leap to their feet, ignoring the flight attendant’s protests, and jam themselves and their packages into the aisle. The mother twists around to call to an older woman in a white headdress three rows down, who is traveling alone. She offers her daughter’s services to help the elderly stranger with her hand luggage. In Egyptian social discourse, impersonal inconsiderateness often goes hand in hand with exquisite personal courtesy.

“Ladies and gentlemen, there will be a slight delay. The tower informs us we are fourth in line to be cleared for landing. Please keep your seat belts fastened.”

The plane circles. The passengers are strapped in, immobilized, obliged to listen to the enervating “landing” music played over the loudspeakers, to the engines making that peculiar whining sound as the plane circles. Just at the moment when, after the long confinement of the interminable flight, your muscles twitch to stretch, your lungs gasp for unrecycled air- just at that moment, you are trapped in your seat, while the plane orbits aimlessly. You are in limbo, a dangerous moment for chameleons. I settle back and close my eyes.

The girl I once was. Where do I start looking? The year I turned nine, the year that was to be the last of the good times? The year I became aware, for the first but not the last time, that my life was susceptible to being caught in the slipstream of history, that a speech broadcast over the radio could change my life forever. The year I first became aware of the burden of belonging: to a name, a past.

According to Proust, the olfactory sense is the most evocative of memory, and it is true for me. With my eyes closed I can catch a whiff of dust and jasmine from the bushes under the verandah of our villa in Zamalek, the morning of the Feast of the Sacrifice, that year that was to be the last before my world came tumbling down.

Where do I start looking? I can close my eyes and get under the skin of the child of nine, but the bride of nineteen is a stranger. In the intervening years I have lost the key to her thoughts and emotions. In retrospect, I seem to have drifted along like a leaf borne downstream. Why did I marry Yussef and leave with him to England? I wish I could go back and ask that question of the girl walking her dog on the beach at Agami- the girl I once was. When could I have changed course?

Sometimes it’s like looking through a kaleidoscope: the individual slivers of colored shapes are the same, but an infinitesimal shift in the angle of the lens alters the composition to form an entirely new pattern. If you examined the turning points in a life, could you pinpoint the precise twists of the kaleidoscope that set the pattern?

The plane circles. “Ladies and gentlemen, we apologize for this delay; the tower tells us we are next in line for landing.”

Some people’s lives are swept along in the slipstream of the headlines; the course of my life was diverted forever the day Siba`yi was assassinated and Sadat saw the writing on the wall. What if I had not run away to France? What if I had never met him again, that stranger from across the sea who had seemed as familiar, the first time our paths crossed, as a face in a photograph you look at every day of your childhood? Why did I follow him across the ocean to that New Hampshire town of snow-capped steeples and ice hockey that I have called home for the past ten years? What if there had been time to go back and read the signposts?

Looking back, I realize that the sea changes in my life have been sudden, and that at the time I thought they would be temporary.

“At this time we have been informed that we are cleared for landing. Cabin crew, please prepare for landing. We should be on the ground at Cairo airport in a few minutes. We apologize for this delay and wish you a pleasant stay in Cairo.” The plane begins to lose altitude and the enervating whine of the engines switches to a purposeful rumble.

What is the reason for my visit? To find two lost children: the girl I once was, and the little boy I left behind ten years ago. Tarek. Ten years of waiting and hoping. Putting each day to bed with a sense of dissatisfaction, of unfinished business. The unbearable ache of the first months of separation dulled to a sense of something missing, of never having permission to be happy. Never a day going by when I did not think of my son, wonder where he was, what he was doing, if he thought of me. The photos, every few months; always a pang mixed with the joy, because they reminded me that time galloped on, that the child grew day by day, a gangling teenager already when the photo I had been kissing goodnight was of a gap-toothed little boy.

I have come back to claim what’s mine, to find out if it is still mine: the past and the future. To discover where I belong.

The wheels skim the ground and the engines are thrust into reverse with a violent roar as the plane hurtles down the runway, then skids to a stop. There is a round of clapping from the Egyptian passengers; it never fails, no matter how bumpy or smooth the landing. As much as a courtesy to the pilot, the applause is the self-congratulation of a fatalistic people on arriving safely. Hamdillah `alsalama. Home safely.

Cairo Airport, finally. I sling my shoulder bag and coat over my arm and head for the passport check booths. The Minnesotan couple follow me in line. I hand my blue American passport to the man at the first booth.

“Do you have a visa?” He asks in English.

“No, but I’m Egyptian-born.”

He looks mildly surprised; perhaps I do not look typically Egyptian. He flips through my passport.

“Seif-el-Islam?” He raises his eyebrows at my maiden name and asks in Arabic, “Any relation to the Pasha?”

There was a time when answering that question would have posed a political liability, when I would have hesitated, gaging my interlocutor’s tone for hostility or secret sympathy. But those days are long past. The man at the booth even used the pre-revolutionary title, Pasha, officially banned by Nasser nearly forty years earlier.

“I’m his niece.”

The man enters the data from my passport on a computer screen, then hands the document back to me with a smile. “Hamdillah `alsalama. Welcome home.”

As I pass through the gate I nod to the couple from Minneapolis, a little awkwardly, because I can see in their eyes that I no longer belong to their world. At customs I push my cart right through the Nothing To Declare aisle. I scan the mass of dark, eager faces beyond the barrier at the exit. One does not distinguish black or white, only infinite gradations of grey in this most ethnically-mixed and color-blind of peoples. Within a few hours I will no longer notice such things, just as I will no longer see the inevitable film of desert dust in the stark sunshine, like a layer of ash over the grey buildings and the sooty cars, the leaves of the trees and the dark winter clothing of the people.

Reading and hearing you, Samia, read from the beginning of The Cairo House I am reminded that is time to pick up this wonderful book for another re-read. It’s universal theme always hits me in a different spot, and I can never get enough of the details about Egypt and Egyptian society, past and present.

Congratulations on a beautiful (also very well designed/navigatable) site! I will look forward to checking it out every month.

Susan Nassar

First, a word of thanks and encouragement to the editors of this superb publication!

I am a devoted reader of Samia’s books, waiting for the next one to land on my desk. This I owe to the first pages of “The Cairo House”(see above), where she masterly expresses the mixed feelings we experience, as expatriates having grown roots in America,” when the plane that brought us back across the ocean comes closer and closer to the ground of what used to be home and in more than one way is still “home” (a similar mix of emotions awaits us back at our home base RDU, but this is not the subject). As a true writer, she does this in a way that is both very personal and (not overly auto-biographical) deeply related to her reader’s own circumstances. This I see as the Proust connection, a sincere, well-deserved compliment. I wish I could write English as well as she does but, as much an adoptive Southerner as I became, I was not raised to leave and failed to become like her a real “chameleon.” Reading this particular book makes me feel what it is.

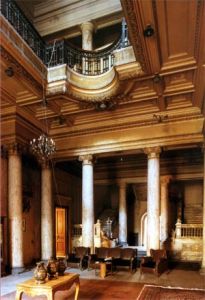

So, so lovely, Samia. You are perhaps one of the most adept chameleons around, and you know I say that with great admiration. You move between vastly different cultures and languages effortlessly and I can’t help but feel that each informs the other so that the whole is greater than the parts. And I love the photo of your family home — majestic! Best wishes with this new publication and your new role here. I very much look forward to future issues and articles. (I submitted a similar comment earlier today but don’t think it went through. In any case, I think this one is better!)

Samia, your voices–both literal and literary–are lovely. I look forward to reading your books, soon.

Samia, it is nice to re-read your introduction to The Cairo House and see that it is now available to so many more who might not have had the opportunity yet to read the whole book. I like very much this new magazine that presents the openness of the South to the global community. Your voice brings an extraordinarily broad expanse to the conversation. It is rich to revisit your comments that being a chameleon enable one’s fellows to rest comfortably aside one’s bicultural existence. As one who also lives in two cultures, but oddly within the U.S, I don’t think of myself as a chameleon. However I remember now when we first settled here in 1978, I didn’t tell people for months that I was a vegetarian. I felt being a Californian and a vegetarian would be too much at that time.

Samia, this is a refreshing format which I am sure many avid readers will find intriguing and expressive of inner most feelings that some find difficult to articulate! Best wishes for a successful journey!