The Clabber Girl

It’s a Thursday night, and I should be doing so many things that I decide to do something else. I have papers to grade. I have a writing deadline to tend to. And the computer in my office is turned on in anticipation of bill paying.

But I find myself in the kitchen. It’s not as though I am going to cook anything. The Crockpot is safely put away, after all.

No, rather, I feel a sudden need to clean out the spice cabinet. I reason it’s been a good while since that’s been done, and the need to clean such spaces arises when deadlines, much like the stars, align.

Or when I open the cabinet door to put the olive oil away and something falls on my head.

The contents of the bottom shelf are assembled on the counter, and it is at this point I wish I could simply just toss everything that I either don’t use or don’t recognize. But I’ve never been one to do that. Just as I’ve never been one to really care about cooking or eating. (I know often one leads to the other but when the former is tended to by someone else I am all the happier.)

No. This assemblage of kitcheny things has nothing to do with cooking, to my mind, though I know that is why they were purchased. The bottles and jars, the tins and boxes, are mere ingredients of a midlife still life that is rife with still-possible possibilities, and missed opportunities, and remembrances of meals made, and meals had, and memories of people who may (or may not) still be a part of my world.

I turn on the radio. Fill my glass with iced tea. Stretch open a fresh trash bag. And, thus, I begin.

The honey is rock-hard. The caramel syrup, the kind you put in coffee and desserts, must date all the way back to my married days, and I’ve been divorced for almost twenty years now. I toss both into the trash.

The salt-free Mrs. Dash was long expired when I sprung it from my parents’ kitchen six years ago (pre–estate sale clean up). I unscrew the lid, sniff the still-seasony scent and picture, immediately, how this plastic container sat on the ledge of their stove. And the thought of standing in that kitchen, in that house that I no longer have a key to, transports me to a vague sea of dinners and other meals but especially dinners, each one planned around the Four Food Groups, and scheduled to begin promptly at 6:00: father, mother, daughter, and son gathered, paper napkins in laps, turns at the conversation wheel monitored, a dog sniffing about for the occasional morsel of meat.

Iced tea waiting in an amber glass pitcher. Baked chicken breasts hoisted from a Corningware pan. After dinner, Neapolitan ice cream scooped into ceramic bowls, or maybe Little Debbie Oatmeal Crème Pies pulled from the lidded stoneware cookie jar, brown and yellow maple leaves depicted on its side.

It was all so predictable, ordinary to the point of boredom, when I was living through it, admonished to clean my plate one porkchop-and-applesauce supper at a time. These days, I look back at the monotony of midcentury suburban life through an appreciative (if more socially aware) lens, especially as I now know firsthand the challenges of feeding a family, of being the one to make the purchasing and the preparation happen. I appreciate these un-extraordinary scenes as slices of imperfect perfection, images brought to mind and into vibrant focus, suddenly, by the used and useless spice before me.

I decide to keep the Mrs. Dash and tuck it into a hidden corner of the cabinet. It will not be lonely. The much-used Lawry’s Lemon Pepper? Keep. The once-used Vieux Carre’s Original Gumbo File? Keep. Paul Prudhomme’s Magic Six Spice? I have no idea as to what that is. I open the jar, sniff. It smells of curry: keep, I decide, though its aroma has nothing to do with that decision.

I turn my attention to the middle shelf and remove its menagerie of oils, cooking sprays, and the little tins and boxes of stuff one finds useful when baking. I examine the small brown glass bottles of extract, each one feeling cool in my palm, each one a witness to batches of cookies I made, say, one Christmassy afternoon, or on a glorious fall evening, the sort that inspires sweetness simply because the usually subtropical clime is finally, blissfully cool.

The lemon extract is expired by more than a year and was never opened; there’s not much left of the Imitation Almond Extract; the Imitation Peppermint Extract is half-full of a liquid that looks so much like Scope mouthwash I am shocked that I even purchased it. But use it I did, though not as often as I had hoped I would. I rarely had time to make things from scratch. Batches of muffins started out in an envelope, trays of warm cookies were cut from logs of premeasured dough, and biscuits were popped from a cylinder.

I can’t say it was the best I could do, but that seemed to be the case when I divorced and started a new career in one fell swoop.

The next item to examine is an open box of Arm & Hammer Baking Soda. It’s three years old. Toss.

Next: Best Choice Corn Starch. Cornstarch? I can’t remember the last time I made gravy, and if cornstarch is used for anything other than that I don’t remember: toss.

Next: Clabber Girl Baking Powder. There’s a lot of information here and there: Gluten free! 0g trans fat! America’s Leading Brand (with an image of Old Glory to get the point across). Still, it is the face featured on the container’s face, and the scene that surrounds it, that draws me in. I adjust my glasses.

That scene is a world in miniature, a story sketched in black and white, an interpretation of life as it no longer is. It’s a drawing so suitable for framing that I wonder if the original is in a museum somewhere, this presentation of a time when the general population knew what clabber was, and used it.

In the foreground is a girl (maybe twelve, perhaps fourteen) wearing a soft dress. Her wavy short hair catches the light, bringing attention to a heart-shaped face. She holds a tray of biscuits, so reticently that it seems she might walk off with them rather than bother anyone about their existence. I can’t tell if she is related to the family behind her or in their employ.

And I know in that moment that, as many times as I had noticed the pretty Clabber Girl before, I had never realized there were others there, as well.

Intrigued, I sit at the kitchen table, baking powder in hand.

Depicted is a Woman’s World—Papa is nowhere to be seen, and, of the children, the girls outnumber the boy. In the background is Mama, in an old-fashioned dress and apron, sitting on a stool. She leans over her lap, intent as she tends to some task. There’s a wooden box on the floor. A small girl standing near clutches something in her fists; the small boy at Mama’s feet, strangely enough, blows bubbles; a third child has her hand in the box that is full of something, but I’ve no idea what. A toy horse, the kind a child would pull with a string, is around, as is a distracted kitten.

Remarkably, there’s more: a wooden chair to one side of the portrait, and a framed silhouette on the other. There is so much going on, so much to look at, that it’s no surprise that no one pays any mind to those biscuits.

Nor does anyone seem aware of what appears to be (the bottom of) a heavy curtain hanging overhead, as though ready to drop and end the tableau at a moment’s notice.

Why would the artist add a theatrical curtain to such a homey and homespun scene? I rummage through the junk drawer and locate the magnifying glass for a closer look.

The curtain is still unexplainable, so I move my gaze to Mama and her task. What I had assumed might be a pair of pants to darn seems to be, maybe, a rag doll, but I can’t say for sure. The long, weird arm that hangs there is disturbing, as is the fact that the doll seems to have no head. Intrigued, I place the container on the counter as I make my way out of the kitchen and into my office, determined to Google search Clabber Girl labels. Surely, seeing this miniature scene blown up on a computer screen would solve all mysteries.

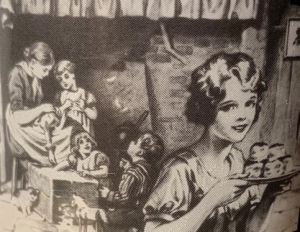

But looking at the same circa 1940 image doesn’t help, no matter how much I am able to zoom in. My search, however, turns up links to images of the previous label, the same basic scene rendered by a different artist, this particular image dating back to 1923. I click to enter this new, tiny world.

Gone is the framed silhouette; the toy horse is replaced by a squat straw basket. The curious kitten is replaced by a playful cat. It’s obvious that what hangs overhead is not a curtain, but a mantel to a large cooking hearth, complete with cooking pots, that the family is sitting in front of.

What also is clear is that Mama is not so much intent as she is a bad ass, doing something I could never do, and that is engage in the act of pluck-pluck-plucking a dead hen. It’s now obvious that the “weird arm” on the other label is actually a limp, wrung neck, and it’s likely that Mama is responsible for that, too.

The girl is clutching feathers. The boy: blowing not bubbles but feathers. And the box? Visibly full of feathers, with no third child about to rifle through them.

By the time I realize what is happening in this scene, I almost don’t care that the Clabber Girl’s hair is darker and smartly bobbed, her garb more tailored, her smile more assured than sweet. And I don’t know what to make of the fact that, in this version, she is far more “young woman” than “young lady.” Someone who could maybe kick up a pretty mean Charleston. A young working woman, referred to as a girl back when women were called such, even by other women, and employed by the woman behind her, feathers flying.

I have to remind myself that though this Clabber Girl is new to me, it actually predates the one I think of as the original. This Clabber Girl is the one who will be dismissed, pushed aside. She will be re-imagined and retooled in order to attract more people to the brand. And in order to do that, she will be made younger.

I close the file. I back away from the desk.

Younger. As in, not in control.

I stand.

Younger. As in, it’s not her idea to make the biscuits.

It’s Mama’s. And even her purpose would be made vague, and her reason for being there less obvious, bad assery reduced to window-dressing.

I stride back to the kitchen, back to the spices I’ve decided to keep. Grab the baking powder tin from the counter. Gaze, with new eyes, at the world encapsulated in the label I’d grown up looking at but never really seeing, noticing only (until tonight, anyway) the pretty face of the Clabber Girl and that plate of biscuits, as I’m sure most everyone does. A pity, really. So much going on in that little world behind her, behind all of us, what with pots on the hearth, and feathers all about, and Goddess hands pluck-pluck-plucking.

Loved this. I, too, grew up with the “later” version. My grandmother always used “Clabber Girl” and her decades of use would have included the earlier one. Thanks for tracking it down and providing the essay.

Thank you! I love that this brand reminds you of your grandmother.

Wow Ms. Laborde! I loved reading this. I have that same baking powder in my cabinet waiting to be useful during my next batch of banana bread. I have always glanced at the old label but never really looked. It honestly made me think about my own life and what label/image am I creating in my home for my daughter. Would my label be me on my phone responding to emails while my daughter is on her tablet eating store bought snacks? I hope not. I hope I am doing something badass and creating memories worthy of a label for a lifetime.

ChiChi, You JUST made my day. Love hearing from my former students, love hearing how they’ve grown, as you have. Go make that girl some banana bread! ❤️