The Mystery in the Mughal Painting

What is the difference between looking and seeing? One might say that seeing is a passive process—your eyes are open, and perception takes place, but not much more is implied. Looking, however, is active, and it implies intention, searching, effort. The test of serious looking is whether you can give an account of what you have examined to someone who has never seen it. Art historians are very good at looking, and the best of them can make it possible for others to perceive what they have patiently discovered by serious looking. There will inevitably be a need to go outside of the painting for information about context and historical reference, but the looking is essential.

An example of an art form that demands such concentration is Mughal miniature painting, an art form that developed in the Indian subcontinent after the Emperor Humayun returned from fifteen years of exile in Persia to retake the throne in 1555. In his entourage, he brought with him skilled artists trained in the Persian tradition of painting. His son, Akbar, assumed power the following year after Humayun fell to his death on the staircase of his library. The court of Akbar was enlivened by the new artwork produced by the combined efforts of the Persian painters in concert with Indian artists of great skill. The result was a rich array of artistic compositions, which were also enhanced by images and techniques observed in works of European art brought by the Jesuit missionaries. The tradition of Mughal miniature painting would continue in northern India, at courts both great and small, up to the British conquest in the late eighteenth century.

The Mughal miniature was typically destined for a place in a book or an album. In either case, the term miniature is deserved, since even the larger compositions were bound into a book that could be held comfortably by one person for viewing. Each image would be created by a team of artists in a workshop, with underlings providing the rectangular frame lines, floral and arabesque decorations in the margins, and gold leaf for appropriate highlights. The top of the artistic hierarchy was not the painter, however; that honor was reserved for the calligrapher, who was easily the highest paid member of the team. This we know from detailed records of the visits emperors would make to inspect the library, when they would glance over the register of manuscripts and see the list of the artisans involved in each work, and how much they were paid. This emphasis on the supremacy of Arabic-Persian script creates a conundrum for modern catalogers. When we have a leaf of paper with a picture on one side and calligraphy on the other, a museum today will typically describe it as a painting with calligraphy on the back. In its original environment, the description would have been the reverse.

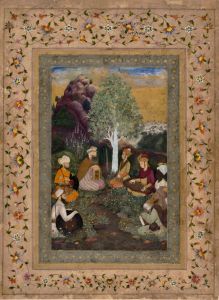

The painting under consideration is in the collection of the Ackland Art Museum at the University of North Carolina, and it is entitled “Prince Dara-Shikoh and Mullah Shah, Accompanied by Five Retainers, in Kashmir, c. 1640–50.” What does the painting actually show? Just to say the minimum, the picture is framed in a couple of layers of borders, the outer containing multicolored floral arabesque while the inner has gold leaf. The scene is outdoors in the countryside: seven figures are seated in front of a tree, which stands in bright contrast to a dark and rugged hill to the left, while on the right one can glimpse a town in the distance just beyond the forest. The figures are all males, wearing the headdresses and flowing garments characteristic of the Mughal Empire. The tree is the plane tree (chenar in Persian), treasured in the regions of Kashmir and Central Asia and frequently found in miniature illustrations. The two figures on the left carry shields signaling their military profession. On the right, a youth plays the santur, a kind of hammered dulcimer, while the figure next to him holds a fly whisk. The man in the lower right corner adds to the scholarly atmosphere by holding a large book. The scene is divided by a stream that cuts down through the center of the painting and is flanked by flowers on every side; the colors are vibrant, except for the stream that was painted in silver and which tarnishes over time. The scene is pastoral, cosmopolitan, and courtly. It evokes a long series of genre paintings that depict the visits of kings to sages and ascetics dwelling in the wilderness. The center of the portrait shows two figures who are obviously the focus of attention, a young man to the right of the tree and a scholarly figure to the left. The scholar is identified as Mullah Shah, the Sufi master who initiated Dara-Shikoh into the Qadiri order; his face is also well known from other miniature paintings. But there is something problematic about the other central figure: it has been literally defaced, and then repainted. And there is a second visual puzzle in the painting, consisting of a cleverly concealed signature by the principal artist. Both the portrait and the signature need to be closely looked at and then connected to external evidence before we can understand them.

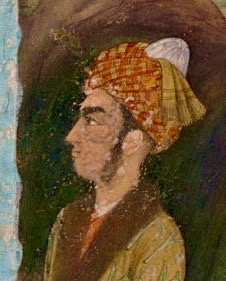

As far as the portrait is concerned, it is easy to find numerous images of Dara-Shikoh by an Internet search; as the eldest son of Shah Jahan (builder of the Taj Mahal), he is famous for his tragic end after being defeated in the war of succession and executed in 1659 by his younger brother Aurangzeb. His sharp features do not at all resemble the weak chin and petulant glance of the young prince in the upper section of the painting. Moreover, this meeting is recorded as taking place in 1640 when Dara-Shikuh would have been twenty-five years old, with his customary mustache and perhaps a beard, so the young boy is obviously the wrong age. But that is not the only problem. The youth to the right of the tree turns out to have had his face repainted (this can be more easily seen if you examine the painting in person). There are globs of paint and flaking that detract from the quality of this image. He is staring somewhat aggressively at Mulla Shah. This retouched image does not fit the painting. How do we explain this?

Let us first look for the signature. Toward the bottom of the painting, directly below the figure of Mulla Shah, there is a dark gray rock crowned with red flowers. If you examine it closely, you will see that there is writing on the rock surface, although it would be easy to miss it. The Persian inscription states, “the work of the slave, the least of servants, Jalal Quli, maternal grandson of Farrukh Chela.” While signing paintings was not a standard practice in the Mughal ateliers, it was not uncommon for the better-known artists to leave their names. Jalal Quli, the main artist of this work, indicates that he is the descendant of a well-known painter from the court of Akbar, Farrukh Chela. From stylistic evidence, art historian Terence McInerney has identified Jalal Quli as the artist known as the “Kashmiri painter,” whose work forms part of the remarkable manuscript of Shah Jahan’s biography that is now preserved in the Windsor Castle library. It is likely that this painting is one of twenty-five unbound illustrations intended for later insertion into the unfinished volumes of that biography. Jalal Quli, probably born about 1600, was painting in the workshops of Shah Jahan by 1633. He was known for his landscapes depicting Kashmir, and it appears that he entered the service of Dara-Shikuh when the latter began to spend time in Kashmir throughout the 1640s.

So it is possible to consider this painting as a depiction of the first meeting of Dara-Shikuh and Mullah Shah. Both Dara-Shikuh and his sister Jahanara became devoted disciples of the Sufi master, and in fact both of them also displayed their literary talent in writing biographical works featuring Mulla Shah. Dara-Shikuh described his first encounter with Mullah Shah as a conversation in which he himself was extremely shy. Mulla Shah, not having met the prince before, asked him his name. Feeling overwhelmed, Dara-Shikuh could only say “a faqir,” or poor man (identifying himself with this Sufi term was certainly ironic, considering that Dara-Shikuh was the second-wealthiest person in India). When the Sufi master pressed him for his name, Dara-Shikuh simply replied, “you know what it is.” He then recited two short Persian verses of his own composition, ingeniously including the name of Mulla Shah in the poems. While this written account presumably portrays the same meeting shown in the painting, it focuses only on the conversation between Dara-Shikuh and Mulla Shah. In the portrait they are shown seated on either side of a flowing stream, recalling the encounter of Moses and the immortal prophet Khizr at “the meeting place of the two seas” (mentioned in Qur’an 18:60), the source of the water of life, and a favorite theme of Persian painters. These associations would lend spiritual significance to this meeting of master and disciple.

The written account of the meeting by Dara-Shikuh says nothing about any attendants who may have been present, or the location of the meeting. What instructions did Dara-Shikuh give to the painter, and how much of the composition was contributed by the artist? Was the prince originally depicted gazing at the shaykh, or perhaps listening to the music of the santur with eyes closed? These questions remain unanswered. But as we have seen, the painting has been somehow altered. How did this happen? McInerney points out that the triumphant Aurangzeb seized all of his brother’s possessions (including art) after putting him on trial for heresy and having him executed. Evidently Aurangzeb had gold leaf painted over Dara-Shikuh’s signatures in his most valuable album in order to obliterate his name from the collection. McInerney argues that Aurangzeb also had his brother’s face erased from the painting as a further banishment. Then when this painting came into the hands of a new owner in the late eighteen century, a new border was added, and a new portrait was painted over the spot where Dara-Shikuh’s face had been. A new inscription was then added to the manuscript in hastily written Persian, making the confusing claim that the painting was a portrait of the Persian Shah, Safi al-Din (r. 1629–1642), the work of the artists of Shah Jahan. While the proposed series of events is possible, there is no evidence to prove it. This theory could be another example of the “good guy—bad guy” stereotypes that have been used to depict the contrast between Dara-Shikuh and Aurangzeb, turning the one into a liberal hero and demonizing the latter as an extreme fundamentalist. Those who are interested in this debate should turn to two excellent new books, Supriya Gandhi’s Dara Shikuh: The Emperor Who Never Was, and Audrey Truschke’s Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King.

The last thing to be observed is that the other side of this painting features an elegant calligraphic composition, written diagonally as was customary. The text is a Persian quatrain generally attributed to the great early Persian Sufi, Abu Sa’id ibn Abi al-Khayr (d. 1049), as follows:

I am sad, but I do not leave your home with sadness;

I only go with happiness, hope, and cheer.

No one goes rejected by a lord

As generous as you; neither do I.

–Written by Sayyid Ghulam Husayn Rizvi

Pretty though the poem is, in this case the visual accomplishment of the painting is so remarkable, despite its disfigurement, that it deserves to be catalogued as a page with a painting on the front and calligraphy on the back. The visual puzzles of the prince’s portrait and the hidden signature deserve to be better known, however.