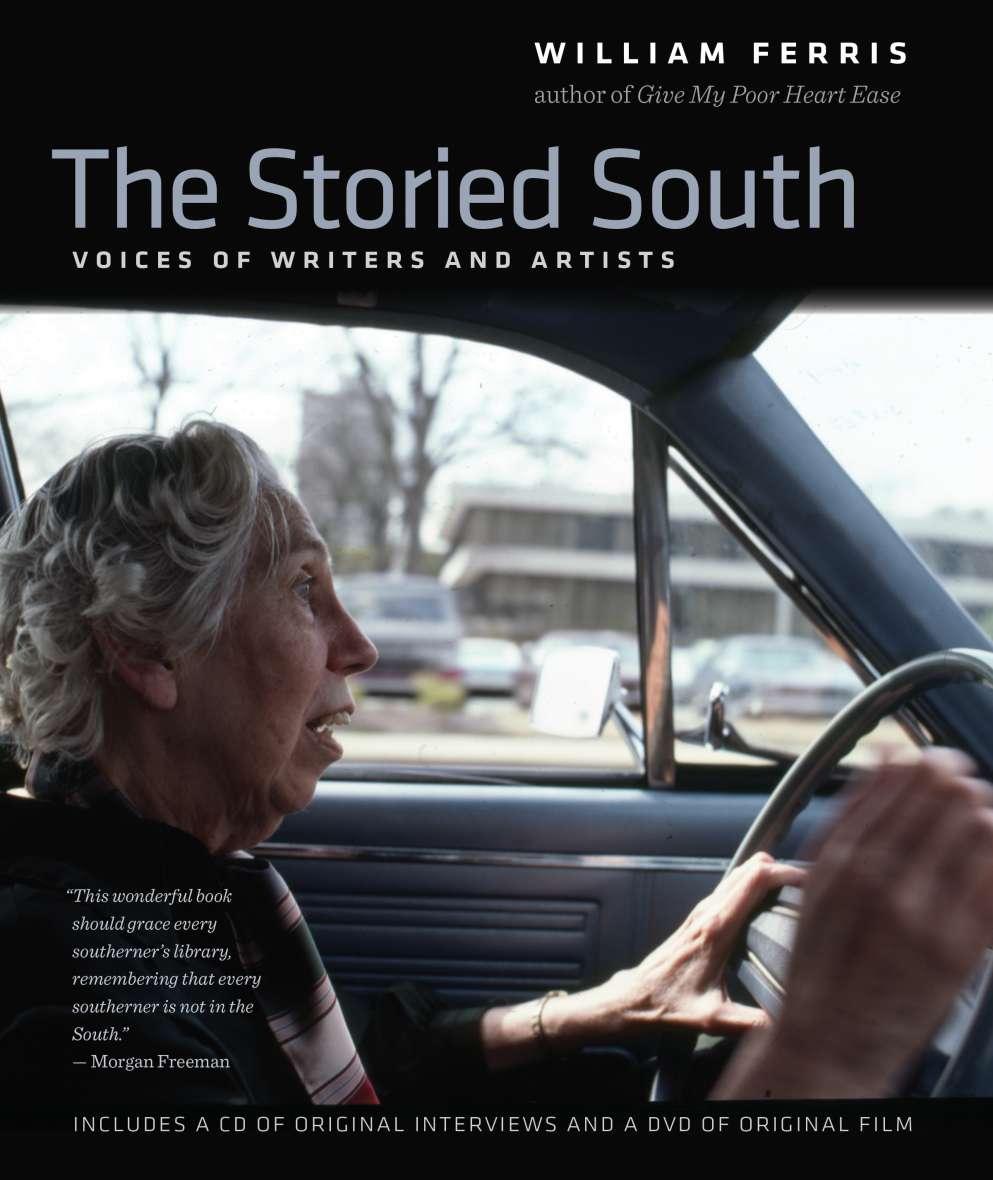

The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists

An Interview with Bill Ferris, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Amanda Brickell Bellows, June 6, 2013

On a hot, humid summer afternoon in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, renowned folklorist and UNC professor William Ferris sat down with South Writ Large to discuss his new book, The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists (UNC Press, 2013). This book features Ferris’s interviews with Southern writers, scholars, artists, and composers, including Eudora Welty, Ernest Gaines, Alex Haley, Alice Walker, Robert Penn Warren, John Blassingame, Cleanth Brooks, C. Vann Woodward, William Christenberry, William Eggleston, Walker Evans, and Pete Seeger.

Below is an edited transcript of our discussion about folklore, storytelling, and The Storied South.

* * *

South Writ Large: Today, Bill, we’re here to talk about your new book, The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists. The book consists of twenty-six of your interviews with writers, composers, photographers, and other artists whose works have been influenced by the South in different ways. The Storied South also features forty-five original photographs, sound recordings, and DVD footage of these interviews.

Tell us, how did your work as a folklorist inspire you to conduct these interviews over the last forty years?

Bill Ferris: Folklorists have an instinct for doing interviews. That is the nature of what they do. They interview people, transcribe their interviews, and study their stories and their music. I am fascinated with the tape recorder and how technology has changed over the years. It gives me the ability to capture a moment in time in which a voice tells a story that at the moment may seem mundane. But when you look back on that story, it becomes more valuable. The actual sound of their voice telling the story becomes almost hypnotic, the more you listen to it.

SWL: How did you select your subjects for the interviews? It seems like you featured writers, artists, musicians, scholars, and photographers who represent the multiplicity of perspectives and experiences of Southerners or those who view the South.

Bill Ferris: These speakers are my heroes and heroines. I admired them first at a distance. Then I was blessed to meet, to become friends, and to do these interviews with them. They were done because I admired each of them, and somehow by luck or accident we found ourselves in the same place at the same time.

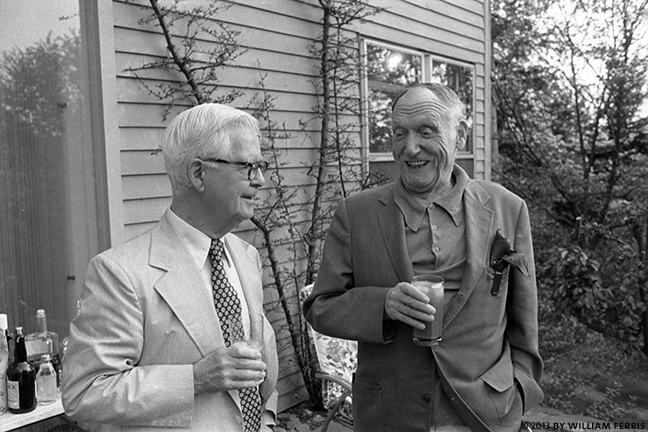

In the case of Eudora Welty, I knew her for many, many years and did a number of interviews with her. Charles Seeger and I met by chance on the campus at Yale. I realized who he was, and he agreed to sit down and talk with me for a few hours. I interviewed each of these people, and our recorded conversations were transcribed. But they were never together. I thought to myself, these are people whom I would love to see at a dinner table together, all talking.

I conceived of this book as a way to bring everyone together—black and white, men and women, old and young—all talking about the South, what it meant to them, how it changed their lives. The book looks back on fifty years of my life and the voices of the truly amazing people who inspired my work as a folklorist and student of the American South. Each person in the book profoundly shaped the study of the South. They helped create the field that we now call Southern studies. Without the work they did as writers, as photographers, as painters, as musicians, and as scholars, the field would not exist.

Many of the speakers are gifted in multiple areas. Eudora Welty and Ernest Gaines are exceptionally fine photographers whose photographs influenced their work as writers. Painters like Sam Gilliam and Ed McGowin were influenced by William Faulkner’s stream-of-conscious literary style in their work as painters.

SWL: One thing that’s very unique about The Storied South is the way you let the voices of the people that you interviewed shine through. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about this technique.

Bill Ferris: There are two ways to present an interview. The first is to include your questions and let the reader shift back and forth between each question and answer. The second approach, which I chose, is to remove the questions and edit the voice of the person interviewed into a single narrative text. I think this approach is more effective because it allows for an uninterrupted portrait of the speaker. My use of this approach was inspired by the literary form know as the dramatic monologue. Eudora Welty, Alice Walker, and Ernest Gaines all use the dramatic monologue in their fiction. It is a device used in fiction and in poetry where you use a single speaker, and through that speaker’s voice you discover their world. So I chose that approach. It was a conscious decision, and I discuss my reasons for using the dramatic monologue format in the introduction of the book.

SWL: Can you elaborate on the narrative link between the Southern artists and writers in your book?

Bill Ferris: Southern writers and the artists have deep, important connections. In the earlier part of the twentieth century, few museums and galleries in the region existed that would feature artists in the region. Artists looked to writers like Faulkner, Welty, and Richard Wright as their role models. Artists were understandably inspired by both the written word and the narrative voice. All of the speakers in this book are in love with storytelling. The title of the book, The Storied South, was inspired by that idea. Southern artists and Southern writers both grapple with storytelling on the canvas, in photographs, in music, and on the pages of short stories and novels.

SWL: How do these interviews help us understand these beloved writers and artists in new ways?

Bill Ferris: These interviews give the reader an intimate, face-to-face relationship with people who are iconic figures in the study of the South. Their names include Alice Walker, Eudora Welty, Robert Penn Warren, and Walker Evans. We know their work, but we are not as familiar with their personal worlds.

Many of the people in this book shared long, deep friendships. Eudora Welty, Robert Penn Warren, and Cleanth Brooks had friendships that endured more than fifty years. Alice Walker and Margaret Walker both shared close friendships with Langston Hughes. William Christenberry and William Eggleston have been friends for over forty years. When you read these interviews, you get personal insights into each person—their friendships, their feelings, and their relationship to the region. Each is defined in different ways by their ties to the American South and by their love of storytelling.

SWL: I thought we’d talk next about the content of the interviews, many of which were done during the civil rights era. Do you discuss the topic of race or the topic of class with any of the interviewees?

Bill Ferris: The topic of race is an ongoing theme throughout these interviews. There is a sense of obligation that speakers in the book must deal with race. Eudora Welty talks about her relationship with black writers like Alice Walker, Margaret Walker, and Ralph Ellison. Alice Walker discusses her relationship to the South and feels uncomfortable with the term “Southern writer” because it often refers only to white writers. John Dollard talks about the difficulties he faced when he interviewed blacks in Indianola because of racial taboos there. Robert Penn Warren speaks about his interviews with Malcolm X in New York and Aaron Henry in Mississippi. The issue of race and class is a central theme throughout the book.

SWL: The world has changed in some ways and stayed the same in others since the civil rights movement began. Do you think that some types of temporal change have turned these interviews into important historical documents that reflect the attitudes and experiences at particular moments in time?

Bill Ferris: These interviews represent a moment that is frozen in time by the tape recorder and the camera. These speakers grew up and lived in an age that existed prior to the Internet. They could not have imagined that their voices and works would be might be globally accessible through the Internet. Our ability to read and hear their voices and to view their faces in a digital form would have astonished them.

What we see in this book is a pre-Internet world, a world that existed before the aftermath of the civil rights movement. Each speaker struggles to deal with race, and their struggle constitutes a period within Southern history. The book is important because we see this struggle from the perspective of many different lives.

SWL: It’s interesting to think about how as a folklorist you’ve lived through all these technological advancements. In your view have they been advancements? What have we lost and what have we gained?

Bill Ferris: It is very exciting for me to see how technology has evolved. The Internet and new digital technology allow me to pull from the dusty shelf my sound recordings, my photographs, my films and merge these different media together. I can create a PowerPoint [presentation] inspired by this book that embeds my photography, sound recordings, and film in it. This powerful new tool allows me to immerse the audience into the lives of the people featured in my book.

The book contains a CD and a DVD, and the enhanced ebook has clips of films and sound recordings embedded in the text itself. This electronic version of my book would have been unimaginable a decade ago. Thankfully, I have lived to see documentary work that I did over the past fifty years transformed and animated through these brave new worlds.

Fifty years of recordings, and films, and photographs are now yoked together and presented in a powerful new form that pays homage to the speakers in this book. It is reassuring to know that conversations shared over the years are now accessible in this way to the reader.

SWL: Here at South Writ Large, a magazine that examines the idea of the “global South,” we believe that Southern experiences can be both American and global experiences. For example, in other countries, the residents of rural regions where music, food, faith or family shape culture and community, these residents might share certain experiences with American Southerners. Do you think that international readers can relate to or learn from your subjects in some way?

Bill Ferris: I agree with C. Vann Woodward that the South is the most global part of our nation. Woodward, who is featured in this book, argues that the South is similar and attractive to other nations in the world because it is the only American region that was defeated and occupied militarily. It is the region most familiar with poverty, illiteracy, and malnutrition. And it is a region that is rich in storytelling and music. People throughout the world identify with the rich, complex history of the South because they have share similar experiences.

There is also a sense of urgency around the globe to capture and preserve the lives of their writers, photographers, musicians, and painters. Whether in Tokyo or Tel Aviv, people feel this urgency. Hopefully, this book will inspire people in other nations to similarly embrace their great writers and artists.

SWL: Looking at this collection as a whole, do you have a favorite interview, or is it possible to pick just one?

Bill Ferris: To ask that I select my favorite interview is like asking a parent to choose their favorite child! I love each of these speakers, and every time I read an interview, I feel I get a deeper understanding of that person. The strongest interview is with Eudora Welty. That is because I knew Eudora so well, and I visited her often over the years. That interview reflects the sheer intelligence of an amazing woman, who deeply loved the place where she lived. She understood the power of the spoken word and knew how to take those stories and transform them into great literature.

I deeply love every person in this book. I learned and continue to learn from each of them. They were my teachers, and I use their work each year in my classes. I look forward to giving my students a chance to encounter them in exciting new ways through this book.

SWL: Summing up the book, what do you think makes this text so unique and do you think there is anything else out there in the market like what you’ve produced here?

Bill Ferris: This book is unique because it offers a panoramic view of major figures who shaped Southern literature, painting, music, photography, and scholarship. While we will find some of the speakers in books on Southern literature, photography, music, and painting, this is the first that brings them all together and allows the reader to encounter the diverse voices and fields that this book embraces.

SWL: In the introduction to The Storied South, you write, “The South is a land of talkers whose stories are as old as the region itself. We tell stories at home, on the street, in settings familiar to every Southerner.” Why is the South so special in this regard? Can you talk a bit about storytelling as a Southern pastime and tradition?

Bill Ferris: Having grown up on a farm in Mississippi, what I remember most clearly from my childhood are the stories that my family and neighbors—black and white—told. Those stories linger in my ear, and I never forget them. They are beautiful, powerful, at times frightening. They define me as a person. My first memory of being alive in the South was the sound of stories. As I grew older, I learned to negotiate and survive by telling stories.

The livestock trader Ray Lum, with whom I did an oral history, spent his life telling stories about horses, and mules, and men. Every Southerner, whether it be North Carolina’s Sam Erwin or Eudora Welty, shapes and defines their craft with stories. To understand the South, we must listen for those stories, because they define a successful lawyer, teacher, or doctor in the region.

No matter what people do with their lives in the South, storytelling is part of it. The story makes life entertaining, beautiful, and dramatic. It adds a kinder, gentler touch to an otherwise dry world, and in the South that is how life is lived.

SWL: Do you see yourself as a storyteller?

Bill Ferris: I do not see myself as a good storyteller, compared to the people with whom I have worked. But I love to tell stories, and I do it instinctively. Sometimes, I feel I talk too much in conversations. Conversations always lead me to a story that I use to illustrate a point. When I lecture in class, I often use a story to make a point. Stories are fair game, whether in a conversation with a friend or lecturing to my students. They help me get through life.

SWL: Do you think that one particular form of storytelling best conveys an emotion or a moment in time?

Bill Ferris: The story form that the folklorist calls the memorat—the remembered experience—is the most common form of storytelling. We often say, “I remember . . . when Uncle Joe walked down to the stream, slipped, and fell in.” Memorats are everyday experiences. Painter Ed McGowin tells the story of his Uncle Sam, who shows up at a family reunion and walks in as the family is beginning their dinner. Then the story turns gothic, as McGowin describes the horrendous act that Sam performs in front of his family. That story has haunted McGowin all his life, and its images appear in many of his paintings.

Stories are important and quite powerful. They go to the core of our memory. If we understand storytelling, we understand the South. In his essay “How to Tell a Story,” Mark Twain argued that storytelling was invented in America and has remained at home here. I believe that the tap root of stories for Twain—and for me—is located in the South.

SWL: How has the work of the subjects of your book shaped how Americans outside of the South and people in other countries view the South?

Bill Ferris: The book features writers like Alice Walker, Robert Penn Warren, Eudora Welty, and photographers like William Christenberry, William Eggleston, and Walker Evans who are iconic figures in American culture. Through their stories, they help the reader understand a place called “the South.” But they also ground the South within the American experience and within the world today. They frame a sense of history and a sense of culture within the twentieth century that is a significant intellectual and cultural foundation for the twenty-first century, because in so many ways the South defines the nation politically, culturally, and musically. Southern worlds, whether we like them or not, whether we rebel from them or embrace them, are deeply embedded in our lives as Americans.

SWL: Let’s talk about storytelling as a global phenomenon. You’ve traveled and conducted research in a host of different countries—you’ve been to Ireland, England, and Russia. Where do you see the tradition of storytelling thriving, if anywhere in the wider world? Why is this adaptive tradition still so important today?

Bill Ferris: The South shares with the world a love for storytelling. The Southern storytelling tradition has deep roots in both Africa and Europe. In Nigeria, the proverbs that Chinua Achebe and Amos Tutuola use in their novels are as important as are Russian stories for Russian writers Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Every society and every culture has deep roots in storytelling. There is no place on Earth where people do not sit down and listen with rapt attention when the storyteller begins to talk. Think of the Griot in West Africa, to whom Alex Haley went to trace his family roots in the Gambia. Those master storytellers have great power and importance within each culture. They make life on this planet worth living. When we understand one group of storytellers, it helps us understand others around the world. Hopefully this book will help with that process.

* * *

Bill Ferris’s interviewees discuss their global influences in The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists

“I would not have dared think that I had a kinship with Tolstoy, or Dostoyevsky. But that is what led me on in reading them. I recognized so much, and I thought, “How good this is. He understands. . . . I [also] enjoy talking to young Russian writers who come to visit. We have an affinity in that we both have a sense of the human problems in the world.” —Eudora Welty

“French history and French civilization and the French language influenced me deeply. I still am a Francophile. There is hardly anything as impressive as what the French intellectual—literary intellectual—was like then.” —Walker Evans

“When I was in Venice, I suddenly had this stream of ideas, which I later called ‘Childhood Imagery.’ I was sitting at a sidewalk café one evening, and all of a sudden I began to have these ideas that were from childhood. They were memories of childhood. I jotted down a whole list of ideas. They poured in. I could hardly wait to get back and get to work on them. I had been in Europe about six months at that time.” —Carroll Cloar

“In college, I loved Camus. He is just a beautiful man. I also really love the Russian writers. I am a moralist. I am very concerned about moral questions, and I have definite feelings about what is right and what is not. Russian writers have a kind of essential passion, and they engage in questioning the universe and human interactions. They really care. I like that. I do not like writers who do not care. I think writers should care desperately.” —Alice Walker

* * *

From The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists by William Ferris. Copyright © 2013 by William Ferris. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

Oral transcription completed with the help of Jonah Dumile