To: Highlander’s Friends Inquiring as to the Location of the Time Capsule

To: Highlander’s Friends Inquiring as to the Location of the Time Capsule

From: Allyn Maxfield-Steele, Co-Executive Director, Highlander Research & Education Center

Dearest Highlander family and friends:

At the time we received your inquiries, we were a bit overwhelmed by news that people once detained by ICE in Texas were being bused back across the South to their homes without food, warm clothes, and any attention to their human dignity.

Rest assured, efforts to meet folks at different bus stops at all hours of the day and night are well underway, and members of our team have chipped in to local efforts to organize supplies and resources to share with people who only have short breaks at each stop. They are doing this with friends across the state who are in relationship to the broader network of southern supporters. This is not work we typically publicize, in part because it’s quick, late-night, word-of-mouth work, and also because publicizing too widely could endanger people on an already harrowing journey.

This came shortly after rapid response work we were doing to support our friends in Eastern North Carolina in the path of Hurricane Florence, which also came right in the middle of our eighty-sixth anniversary Homecoming celebration, which also fell amid the regular educational work we’re moving throughout the South. Plus, one of the chickens got sick, and there is a heated debate among the staff about where we should put a basketball hoop. These are among the reasons I have not been able to reply as quickly as I would have liked to questions about the exact location of the time capsule.

Put briefly, I have heard that the time capsule is somewhere around where the tether ball pole used to be. As for the tether ball pole, no one really talks about it anymore, and it was just in the last month that I remembered it used to be there, right in front of the old (albeit recently renovated) dormitory.

I haven’t lost sleep over the tether ball pole’s absence. Out of the nearly 200 acres and multiple buildings and other things that fall under the purview of our Building and Grounds team, any time we can save for them to attend to other pressing infrastructural concerns is a gift. We ask so much of them.

For example, the team worked together to pick up a host of new rocking chairs for the Workshop Center meeting room. These new chairs will replace some of the older ones—they’re also much more comfortable. Candie Carawan, whom I’m sure you all remember, told us once that staff and workshop participants used to sit in a variety of couches and chairs while meeting. The need for new seats about thirty years ago led to the discovery of some economically priced rocking chairs, which staff at the time scooped up in bulk.

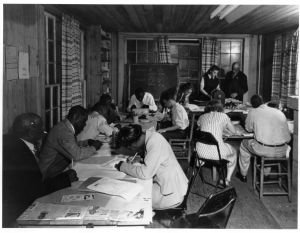

- Main Building with Students

- Highlander Center today

Now that the rocking chair has become an icon of what Highlander is all about—getting people together to sit comfortably and talk and learn from one another about each other’s struggles and to build collective visions for a transformed world—I can’t imagine we’d ever treat the rocking chairs like we did the tether ball pole. We’d have to answer to the thousands of freedom fighters who have come off the frontlines to Highlander over the years. Hence, we buy new rocking chairs and can’t remember anything about the tether ball pole.

Besides, rockers relax, and tether ball hurts. All I can remember is the taller kid in elementary school who could serve the ball with one massive swat and whip it around the pole in an almost instantaneous victory. There he’d be: a big, insidious grin, towering over those of us who just wanted to play, but who were instead pummeled into accepting defeat.

If anything, I guess tether ball was a kind of recreational metaphor for our work. At Highlander, we help people play to win . . . together. We work with groups of emerging and established leaders across the South, which includes Central Appalachia, and invite them to come together to figure out how to take on opponents whose strategy is often to overwhelm and intimidate and manipulate regular people into feeling like they are powerless.

Highlander does this through a range of educational methodologies we have identified over the last eighty-six years: Language Justice, Participatory Action Research, Cultural Organizing, Intergenerational Organizing, and Popular Education. We practice these methods, and we help people practice them for use in their own organizing efforts. We create what we often call “containers” for these methods to come alive. Now, among our educational containers is a year-long fellowship program focused on Central Appalachia, an annual leadership program called Seeds of Fire for young people between ages thirteen and seventeen and their adult allies, and a curricular tool called Mapping Our Futures. Common across all of the people we bring together is a hunger to connect struggles across community, state, and nation.

Beyond direct educational work, which many of you have experienced in one form or another, we offer administrative support in the form of fiscal sponsorships, which helps organizations like Power U Center for Social Change and the STAY! Project thrive and grows additional infrastructure for social movements. We also serve on multiple united fronts and coalitions, such as the Southern Movement Assembly, multiple tables of the Movement 4 Black Lives, and the Southern Connected Communities project.

At our most mythologized, Highlander can function as a person’s place-based manifestation of a centrifugal force—a kind of tethering north pole for those swept up in the struggles for bending the moral arc of the universe. A workshop participant once said that coming to Highlander was like “coming back home to a place I’d never been.” Although we can’t promise that similar feeling of home for everyone who visits, we take very seriously the significance of stewarding that kind of experience.

At our best, we strive to turn our workshop center full of rocking chairs into a place where people can practice democracy and learn how to think differently . . . together. We try to help people tie their experiences to one another, and we do this without a primary focus on one set of issues. One of our elders, Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon, once described Highlander as having an educational approach that allows us “to move through time.” Dr. Reagon’s insight shows up in long-haul accompaniment we offer to leaders in front-line communities, and it shows up in how we encourage people to understand the long-haul nature of social struggle.

Given that, I understand why people are concerned about the location of the time capsule. In movement moments like the one we’re in right now, a lot of people are hungry for lessons and points of connection to the past. It’s precisely the reason that we are building the Septima Clark Learning Center, which will house our storied library and archives as well as a large multipurpose space. Septima Clark was on Highlander’s staff from 1956–1961 as our Director of Education. Her work to develop and expand the Citizenship School program throughout the South was instrumental in shifting black political power in the era of Jim Crow. The program was among the work that Highlander did during the black freedom struggle of the 1950s and 1960s that threatened the white supremacist status quo. As you probably recall, the local, state, and federal authorities tried to shut us down in 1961, but we survived that attack, moving to a new location and picking up where we left off. Our endurance means that we’re a place that works to hold and share memories so that we can bring our ancestors and future generations into conversation with one another about the world we all deserve.

It’s true: at Highlander, we stand on the shoulders of giants like Septima Clark and the many thousands of other grassroots leaders, including Jim, who people say buried the time capsule, which brings me back to your original question.

In short, no current staff member remembers precisely where the time capsule is buried. Aside from the tether ball pole theory, some think it’s in the same spot where Children’s Justice Camp campers roll out the make-shift water slide each summer. Others say it’s closer to the igloo made of privet. Regardless, we’ll be in touch with Jim at our earliest convenience and will be back in touch.

I enjoy the chance to update people on what we’re up to these days and the kinds of resources we can offer, so I hope you haven’t minded this lengthy note. There’s just so much to share.

All my best to you and yours in these critical times,

Allyn

Since 1932, Highlander has been a school for grassroots leaders that works to catalyze movement building and social change work in the South, which includes Central Appalachia. Allyn has served has Co-Executive Director alongside Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson since January 2017. They still need to figure out where the time capsule is buried.