Wendell Berry

Excerpted from Step into the Circle: Writers in Modern Appalachia, edited by Amy Greene and Trent Thomson

Wendell Berry is driving us with the windows down, and the August wind is rushing into the cab of his truck. A working man’s truck, complete with a metal toolbox and a coil of chain under my feet, two tobacco sticks on his dusty dashboard, and—best of all—his beloved border collie, Liz, in the back, her large brown eyes touching mine every time I look toward her. When I was first introduced to her, Wendell said, “This is Liz. I don’t like to be without her or my pocketknife.” Then Liz jumped into the pickup without having to be told and we took off.

Wendell is showing me the land he loves on the day before his eighty-fourth birthday. Most people might imagine rolling pastures with neat swirls of hay and shining thoroughbreds. But this is the man who wrote the masterpiece “The Peace of Wild Things” and he has seen to it that his land offers concord to the untamed. We are on a gravel road where the air grows green with leaf-light. On my side of the truck there is a steep bank rising skyward. On Wendell’s side the land drops down toward the meandering stream called Cane Run, whose waters flow calmly against sandy banks but possess a music when they swirl about in the exposed roots of beech trees or stumble over small congregations of rocks. Most of the trees are thin, and when I notice this Wendell tells me that all of this land was once cleared to make way for tobacco fields in which he worked as a young man, just as I did as a child. “It’s a gone way of life,” he says as we remember the beauty and misery of setting the plants, staking them, hanging the tobacco in the stifling, fragrant heat of the barns. We both recall the cold depths of a swimming hole after working in the fields all day. The camaraderie. The aunts on the setters, chattering over the groan of the tractor. I was once a twelve-year-old boy, beaming with pride as I drove the truck across the fields. Wendell was once a man in his early thirties, fists on his hips as he looked out at the tobacco planted across the bottomlands.

Despite being cleared as recently as fifty years ago, there are occasional elderly trees, too. I spy a sycamore that must be two or three hundred years old, and Wendell stops in the road so we can spend a moment with it. I am reminded of one of my favorite poems by him, “The Sycamore,” and its lines: “In the place that is my own place, whose earth / I am shaped in and must bear, there is an old tree growing.” The really interesting phrase to me there is “whose earth / I . . . must bear,” and I think it reveals a lot about the man as well as the poet.

I sneak a glance at his clear blue eyes as they climb the branches of the sycamore, and there it is: grief. Wendell is a jovial man. He laughs heartily, tells bawdy tales and dirty jokes, and speaks often of love and contentment. He possesses much joy, but that somehow makes his constant grief even more noticeable. The sadness is not only in his eyes, but also on the backs of his hands. It rests across his shoulders. He is one of those people whose constant attention to joy reminds him, all the time, that there is much suffering in the world. And he is incredibly conscious of that pain, whether it is happening to farmers who have been systematically knocked out of work by big industry and the government, or mountainsides that are being obliterated, or the fact that a whole lot of people just don’t pay any attention to the natural world at all.

Perhaps this is what we love most about him, our Wendell. It’s what I love most, at least.

I also love that he has let these many acres grow wild. He points out a few experiments. There is a trinity of box elders, their leafy branches praising in the slight breeze. “I cut back some of the trees to give them light, and they’ve done very well,” he says. He tells me stories of the land and its people—inseparable. All in all he and his wife, Tanya, now have 117 acres here. His people have known this land since his mother’s great-great-grandfather and his father’s great-grandfather. He and Tanya have already made arrangements for this land to become a natural conservancy as an agricultural conservation easement through the PACE (purchase of agricultural conservation easement) program, he tells me. “Eventually it’ll be an old-growth forest,” he says. This will take two hundred years, and although Berry knows he won’t ever see it, he is pleased to know that someday it will exist, right here.

Back out of the holler, the tires of his truck hum on the pavement. The river flashes by through the thick trees on my right—sluggish and dark green in summertime. Then we are climbing a mountain even though we are at the edge of the bluegrass region. I’m surprised by how Appalachian it feels here since we are many miles west of the mountain range. “The difference is that in eastern Kentucky, you go up the mountain and then you go down it,” Wendell explains. “But here you go up to the next ridge.” At the top of the ridge is the little town of Port Royal, which possesses a couple of churches, a bank, and a restaurant where the parking lot is crowded with vehicles since it is noon. There is also the post office, which Wendell frequents quite often. Today he is mailing off eight letters. He tells me to wait in the truck, and he hops out like a teenager and bounds inside.

I am thinking how surreal it is to be going to the post office with one of my heroes. With one of the people who shaped me not only as a writer, but also as a person.

Wendell has allowed me much joy, but he’s also filled me with grief. Both of those are good things, as it is wrong to go through the world blindly, to not take note of the destruction, of the suffering of others. We cannot be full people if we live blissfully ignorant. For many years now Wendell has been one of the people who has taken hold of our chins and turned them toward the beauty and the horror. They exist side by side in almost all of his work, and he has spent his career making us aware. There’s a very good reason a recent documentary about him (in which he refused to appear on-screen) is called Look and See—this is how he has lived his life, and this is what he has taught so many of us. Bearing witness, however, brings along the sad knowledge that there are so many battles to fight and that we can never do enough. But Wendell has always tried his best to do his most, and he’s asked the same of us.

About four years after my first novel was published, I received a letter from Wendell inviting me on a fact-finding mission. I was amazed that he knew who I was. In the letter he said that the form of coal mining known as mountaintop removal (MTR) was ravaging Eastern Kentuckians, and since our legislators were rubber-stamping the devastation, it was up to the state’s artists to do something about it. He had planned two days of information gathering. Artists who attended would participate in small-plane flyovers so they could see the full breadth of the mining. They’d walk a healthy mountain with a local man who would show them its medicinal and food values. Finally, they would listen in to an open community meeting where people in the area would be invited to come tell their stories of living near MTR operations. Would I come along with them?

I had always identified myself as an environmentalist. I had grown up near a large strip mine that forever changed our community. For years I lived in the noise and dust of the local mine. I saw the beloved ridge across from my childhood home reduced to rubble. I watched as our narrow road became domineered by overloaded coal trucks and stamped with the tracks of dozers. I knew what mining could do to a piece of land. But I was also raised in a family who had risen up out of poverty in large part due to coal. I knew the issue was complicated, but speaking out against coal was not: where I’m from one simply didn’t do it, although this hadn’t always been the case. During the bloody coal wars of the 1920s, Appalachians had gone to war with the coal companies for safer working conditions and better pay. Even when I was a child in the 1970s and 1980s, I was aware of the increasingly violent strikes that were happening. When I was in high school, more than two hundred people were arrested for civil disobedience while protesting for safer mines just over the West Virginia border, less than two hours from where I lived. But by the 2000s, the coal industry had largely accomplished its goal of ridding Appalachia of the unions and indoctrinating people with the belief that without coal, we had absolutely nothing else. They spent millions on campaigns to convince people that “Coal Keeps the Lights On” and that to even think of any other kind of economy was foolish. They flooded small-town festivals with free t-shirts and handed out coloring books at our local schools. The propaganda was constant and very smart in that it aligned coal with our identity — the most important thing to Appalachian people. To some degree I had become as brainwashed as everyone else around me, although I was disgusted daily by the environmental devastation I was seeing. I had woven environmental issues into my first three novels, especially my third one, in which three women lie down in front of bulldozers to protect their family land from strip miners. But as soon as I read Wendell’s letter, I knew that I could no longer quietly think and write about the issue. I had to act.

Once I did the flyover, walked the mountain, and participated in the community meeting, I was fired up. For the next few years the issue of mountaintop removal would become my main concern after my family and my writing—and even took over the writing for a while. Wendell mobilized many artists in Kentucky to join forces, to witness what was happening and then report on it. He was at the forefront of bringing together writers, photographers, musicians, and other artists to make the issue more widely known. Our main goal was to let people know mountaintop removal was happening and then hope that they would join us in protesting. They did.

One time I went along with Wendell and several others, prepared to be arrested if our demand to meet with the governor of Kentucky went unheard. I watched as a lawyer’s phone number was written in ink on Wendell’s forearm. The governor talked to us briefly in the hallway but would not offer a sit-down meeting, and we refused to leave. The governor was too smart to have us arrested—he likely imagined the public outcry if Wendell Berry was led out of the state capitol in handcuffs—so he invited us to stay in his office. And so for three days Wendell and thirteen others stayed there.

That first night I have an image of him I will never forget: a jacket rolled up under his head as he lay on the marble floor of the governor’s office, reading a ragged copy of a Shakespeare play. He was seventy-seven years old then. During that time I had known him about seven years but still could only bring myself to call him “Mr. Berry.” I addressed him as such as he lay there and his eyes met mine. “Don’t you think it’s about time you called me Wendell?” he asked. Ever since, I have.

After three days of occupying the governor’s mansion and becoming international news, we went out to greet the thousands of people who had congregated on the front steps of the capitol. When Wendell appeared at the podium, a roar rose from the crowd that caused goose bumps to run up and down the backs of my arms and tears to spring to my eyes.

The practice of mountaintop removal continues, but many more people know about it and oppose it because of the leadership of Wendell and those he called into action. It would have been easier for all of us to turn a blind eye to what was happening. That is how we survive so much. How, after all, could we get through the day if we thought of all the atrocities happening in the world at this moment? But Wendell held our feet to the fire and asked us to join him. We couldn’t refuse him because we knew he was right. I’m grateful for the grief he gave to me. I wanted to say that to him when he stepped high out of the post office and jumped back into the truck after giving Liz a pat on the top of her head, but I didn’t. Articulating the origins of our affections to someone are often too awkward to do, so we keep quiet.

We leave the post office and Wendell drives slowly through Port Royal—immortalized as Port William in his novels—and looks mournfully on some of the empty storefronts. “Way back, on a Saturday night, there would be so many people downtown you couldn’t stir them with a stick,” he says. He shows me the house where his mother grew up, the farm his ancestors worked, and the Baptist church his grandfather cofounded. He tells me with delight that his grandfather was dissatisfied with how close the builders were planning to plant the church to the road so he waited until after and moved the stakes so it’d be situated more to his liking; the builders raised the building, none the wiser, and it stands there still today. Beyond the church is a kempt graveyard. “My people are all buried there,” he says.

Back at home, Tanya has made lunch (in our trio’s parlance, it is dinner), like she does every day. “We eat together three times a day,” she says as she sets out the food. “That’s important, I think.” There is meatloaf (“Leftover from last night,” she says to me, with a brief smile), coleslaw, new potatoes, and a sliced tomato. There is an elegance about Tanya that is especially noticeable because she is so very no-nonsense. She always carries a keen intelligence about her and she does not suffer fools, yet kindness shines out of her face. No one would ever guess she’s in her early eighties—her face does not betray this, nor does her dexterity in her kitchen. Her first book, a folio of photographs called For the Hog Killing, 1979, will be published soon, but she is too modest to talk about it. When I ask about the exact release date, she shrugs. “Oh, I don’t know a thing about that,” she says.

For anyone who knows him, it is clear that there is no Wendell without Tanya. He rarely says the word “I” without preceding it with the phrase “Tanya and.” Sitting together at the eating table, they are like two parts on the same machine, finishing one another’s sentences, complementing each other’s stories. Occasionally Wendell misses a word or two because of poor hearing, and Tanya yells out to him to clarify. They are partners, and seeing them together helps me to strengthen my own marriage. It is hard to be in the presence of these two and not feel like you are always learning something.

Similarly, it’s difficult not to hang on every word that Wendell says, eager to catch the wisdom in every sentence. But it is important for us not to make Wendell into a saint. He would not like that. And he’s not a saint. He’s a real human being, with joys and sorrows, with attributes and faults, some of which have been on display while he’s onstage or in his writing. Only a complicated person could create poetry, essays, and fiction that speak so soundly to the human experience and resonate so firmly with so many of us.

Our dinner conversation is about the sad news of the world, friends we have in common, and books. Tanya is a voracious reader, especially of novels, and tells me about her recent favorites. Wendell, who has long loved Ben Jonson, is reading him again, and is particularly taken with the tale of Jonson’s walk from London to Edinburgh. Our talk is one of laughter and sadness. Often the laughter comes at points in discussing the modern political atmosphere when the only other sensible reaction would be to cry. Wendell has lost patience with all sides of the argument, both liberal and conservative, and fears that constructive conversation has come to a halt not only in the halls of Congress but also in living rooms, beauty salons, and front porches. But here we are, three people, who, despite having much in common, also have many differences and are busy in discussion pocked mostly with affection for one another and for our country. “Obviously there is some risk in making affection the pivot of an argument about economy,” Wendell started his 2012 Jefferson Lecture. It seems to me that joy, sorrow, and affection are the three things always present in a conversation with him.

There are strawberries, pound cake, and custard for dessert. We savor the taste of summer together.

Out on the porch a nice breeze rises off the Kentucky River and washes over us as we visit together. The little house sits only a hundred steps from the river, Wendell tells me, and obviously he takes great pleasure in this. As we look out from our perch, Wendell tells me the history of this spot of land that was once the major waterfront for Port Royal. There is an old store just down the hill that is now used for storage, and Wendell knows the exact date that it closed, the name of the man who ran it, and stories of the people who used to congregate there. Liz stands nearby, tail flapping easily, her eyes latched on his face as he talks, waiting for his attention to fall upon her. Wendell moves across the porch and squats down to put his hand out toward another border collie who has been hiding under a wicker chair. Her name is Maggie, and she is obviously much older, with a whitened muzzle and a humble, bent composure. She touches her tongue to his hand and props her head back atop her paws. Wendell looks around to me with sorrow on his eyes. “Maggie is an old dog now,” he says.

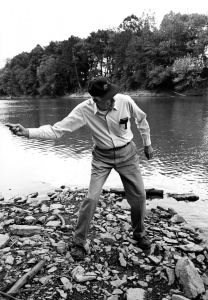

When I leave, Wendell and Tanya perform the southern tradition of standing on the porch until I have left, waving and calling out as I skip down the steps back toward my car at the foot of the hill. When I have disappeared from their view, I turn around to look back. They cannot see me, but I can see them, hidden as I am in a little copse of summertime trees. Tanya slips back into the house, but Wendell remains for a moment, his fists on his hips. He looks out toward the river, hidden from his view by the lush green trees of August. (“I go among trees and sit still,” he famously wrote.) He has told me that once the leaves fall, he will be able to see the water again, from his front porch. Today he is bearing witness to the trees, and they are a gracious plenty. Once autumn comes, he will look and see the river, churning, rolling.

Excerpt from Step into the Circle: Writers in Modern Appalachia (Blair, 2019). Reprinted with permission from Silas House and Blair.

Two of my heroes. I grew up in Knox County

And married a girl from Lsurel County.

Thank you for sharing this story! My wife, daughter, and I had the great honor and pleasure to have a similar visit with the Berrys in 2015. I will never forget it.

This writing is so full of grace and beauty not to mention just the sweetness of the writer and the ones being written about. I am blessed to have read it.

Simply beautiful.

My only words are “Thank you, thank you.” My Kentucky heart is full.

Wonderful.

Thank you.

Thank you so much for this. I experienced the beauty and pain of it. His writing has been the most influential of my life. My ancestors were from the southeastern mountains and I spent time there as some of them were still living when I was growing up. They’re buried on top of a mountain at a place known as Patty’s Rock on the Kentucky River. Your words are beautiful.

I am pleased that Silas House and Wendell Berry are friends. Bless you, both!

Took me back to my birth place. Clay County – precious memories and being torn between the economic difficulties or preservation of the beauty of our mountains.

Thank you for this, Silas. Our world is better with you and Wendell Berry. Beautiful words to begin this day!