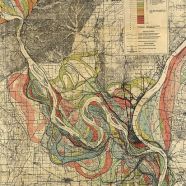

From Fisk’s “Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River”. http://tinyurl.com/h7ehrqh

Share This

Print This

Email This

A Steady Stream of Leavers

When I was a child in Laurel, Mississippi, in the 1960s, in the years before I set foot in America’s Great Migration stream and let it wash the native soil from my roots and carry me to California on a tide that had already carried millions of black Americans away from the South, I remember watching the black teenaged boys, with their swagger and ambition, grow restless with boredom and the racist Jim Crow system that circumscribed and limited their lives. The ones who made good on the boast of their swagger enlisted in a branch of the U.S. military or boarded a Greyhound bus heading straight north like Canadian geese to places like Chicago and Detroit. Sometimes they came back to visit, looking spit-shined and polished, with tales of glamor and prosperity about life lived elsewhere. Sometimes they came back more defeated than when they left, with bad habits and the burdensome shame of having failed to make it up North. Mostly they didn’t come back. They were just gone, swallowed up in that magical Promised Land that the world outside of the South represented for me then.

My mother tells me that it wasn’t just the teenaged boys that migrated north. It was teenaged girls and whole families too. She remembers a steady stream of leavers from the time she was a girl growing up on a sharecropping plantation with her parents and six siblings in the 1930s and ’40s in rural Mississippi. She says she never thought she would become one of the leavers.

But she did. The whole family did. We uprooted ourselves and became migrants—part of the permanently displaced in search of the American Dream.

In The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson notes that some six million black Americans left the South for points north, east, and west between 1914 and 1970. They were all looking for better lives for themselves and future generations. Some succeeded and some failed. For the migrant there is never any guarantee that one will thrive in the new land. But that prospect of failing doesn’t stop the yearning that calls people to voluntarily migrate, seeking greener pastures. My own story is an example.

Growing into adolescence in Mississippi, I developed a quiet ambition and swagger of my own, and I started to feel restless like other teenagers before me―though the word migration wasn’t part of my vocabulary and I wasn’t interested in the North so much as I was interested in places I read about in the books I checked out from the library. I was interested in traveling to places like Paris and New York City and Boston. I wanted a life different than what seemed easily available for a female like me growing up among the working and abject poor in my small, racially segregated Mississippi town.

At first I had lived, without much thought, inside the lines that were drawn for me by the facts of my gender, my family’s financial struggles, and the dangers of the racial divide, those “separate but equal” policies that defined the circles inside which I could live my life. But having been an avid reader from an early age, I understood that there was much more to the world than what was on offer in my hometown. And as I got older and my awareness extended beyond my insular community, I found myself wanting some of that “more”—more material goods, more freedom, more options. But how would I get more? All indicators seemed to point toward leaving.

***

My mother was the second oldest of seven children in her family. When she was seventeen, her mother died. A year later her father died. My mother and her older sister joined forces with their maternal grandmother to continue raising the five younger siblings—four boys and one girl. Over the next few years, my mother’s brothers grew to be restless, ambitious teenaged boys who were not content to toil as field workers on someone else’s farm or work in one of the local lumber mills—the primary work available to them as young black men in that part of Mississippi. So one by one, as they got old enough, they joined different branches of the U.S. military. My mother remembers signing papers for one brother who was not yet eighteen when he was ready to enter the military, so eager was he to get away from what would have been his fate had he stayed. My mother watched them go—two to the Army and one to the Air Force. They fanned out across the United States and circled the globe.

It took them a while to remember home.

My uncles returned in the late summer just before the start of my tenth-grade year. The oldest one had been gone for more than fifteen years. After his stint in the military he had settled in San Francisco and taken up work as a longshoreman on the waterfront there. The second in line spent his time in the military working in telecommunications. Upon leaving the service, he parlayed the knowledge and skills he had acquired into a well-paying, well-respected career with the phone company in San Francisco. The third one was about ten years into what would become a twenty-seven-year military career.

From my teenaged perspective, the three of them were all spit-polished and shined, dapper in the way they dressed, like the boys who came back to visit from up north to brag about the better lives they had up there. My uncles’ English was smooth and refined with nary a trace of rural Mississippi in it. Their wallets were full of money that they spent freely on us for food and school clothes. They even arranged to pay the private transportation fee for my cousin, who was the same age and in the same grade as me, to ride the several miles we would have had to walk to get from our house to the only black high school in my segregated town. My uncles reassured us that their money would be easily renewed when they returned to their respective permanent jobs and homes, worlds away from mine.

In the week and a half of their visit, they followed us around in our daily routines. By this time, my stepfather was no longer in the picture, and we were a single-parent family of eight children (six of us belonging to my mother plus two cousins, the children of her older sister who was killed in a car accident a few years earlier). My mother had work on a processing line at a poultry processing plant. The pay was much better than the domestic work she had done for most of my early childhood. Her single income now surpassed what she and my stepfather, a farm and construction laborer, used to bring home together. We had moved to a bigger house, and though we didn’t think of it this way, we were still living on the edges of poverty―“going nowhere fast” as one of my cousins would later say. It was the shocked and distressed responses of my uncles to our lifestyle that really threw our circumstances into relief. Their conversations highlighted the grave economic inequities between life on the black side of town and life on the white side; the harshness of the racial lines we had to tow; the growing tension around the outside push to desegregate the public schools; and the still limited job prospects for young black people especially.

My uncles had been away too long, they said. They had forgotten just how difficult life was for black people in our little corner of Mississippi—the poverty of so many, the discrimination against all. Their visit had reminded them why they left and what it was they had left behind. They were pained to think of part of their family struggling under the harshness of life in Mississippi in 1969. So when the two uncles who lived in California went home, they started hatching a plan to get us all out. They said it would take them a couple of years to pull together the money to fly the nine of us out (my mother, my siblings, and my cousins) and get us set up with a place to stay.

The plan changed when the school desegregation issue in Mississippi heated up in early 1970. The federal government was forcing the issue, and the state and policy makers in my town began discussing overhauling the school system to accommodate the government mandate. There was talk of the schools shutting down and teachers going on strike, and there were threats of violence on both sides of the tracks. What concerned my mother and her brothers were my female cousin and I who were finishing up tenth grade that year. My mother had always leaned on the notion, and pushed it heavily, that education was the magic potion that would help to float us above the poverty and chaos and stunted possibilities for most blacks in our town. If the schools were shut down in protest, or teachers refused to teach, we would not be able to finish high school in time. And what kinds of trouble might we, restless teenagers already, fall into with empty time on our hands and no prospects for moving forward in life? Neither my uncles nor my mother were comfortable with the thought of our succumbing to early motherhood and marriage or joining in the active fight for civil rights going on all around us in our hometown and other parts of the South. So behind the scenes my mother and her brothers decided that my cousin and I would go to California after finishing tenth grade and enter eleventh grade in San Francisco.

“You two are at that age where you need to start thinking about the future,” my mother said when she introduced this plan to us. “I want something better for y’all than what I’ve had. Things are better for black folks in California. More doors will be open for you there.”

My cousin and I didn’t even need to let the air cool around her words. My mother didn’t have to convince us. We had already assessed what awaited us in Mississippi. Some of our high school friends were already dropping out of school to have babies, and most black women who worked outside of their own homes, which was most of them, were working in some type of domestic or caretaker jobs, or in food industry or agriculture. Our uncles were offering us the possibility of entry into that wider world, the golden Promised Land of California. Even better than “up North,” my cousin and I agreed. Of course we would go for this shot at a better life! We would move to California, even though it meant that we would have to live with our longshoreman uncle and his wife and three children for at least a year. It would take that long for him and our other uncle who worked for the phone company to save money to bring the rest of the family out.

In the summer of 1970 my cousin and I boarded a nineteen-seater airplane heading for California at the small airport in my hometown. In the fall of that year my town’s decision about how to integrate the public schools brought with it massive upheaval in the school system and overt racist violence. From the safety of my uncle’s home in San Francisco, my cousin and I heard reports of the ordeals my three school-aged younger brothers and her brother faced while being bused to schools on the white side of town.

A year later in the summer of 1971, my mother and the rest of my immediate family boarded the same nineteen-seater airplane my cousin and I had taken and headed west. We had come to California with the usual migrants’ hopes for a better life and a real shot at the American Dream.

***

In theory the migrant in America has moved to a place that has the same language, the same laws, the same government as the place she left behind, but in reality to move from one region of this great country to another is to traverse into foreign territory where the laws are not really the same. Each state government has its own laws and rules, and the federal laws get interpreted differently in different places. Look at how Mississippi had skirted the federal laws from the time of the Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 until 1970. This kind of individualized interpretation of the world extends to the spoken language as well. Even English is interpreted differently from place to place.

So migrating within the United States calls for reconfiguration, reimagining, and finally reinventing one’s self. This reconfiguring is no simple task, but the hopeful migrant is so anxious, so eager to fit, to belong, so sure that her ability to gain all that this Promised Land has to offer depends on her facility at adapting, that she will do it. As she adapts and reinvents and acquires the accoutrements of this new land, she must give up some things, some of which she doesn’t even know the value of yet. She gets busy letting go and trimming and reshaping herself to fit the contours and tongue of the new land. This was especially so coming from the South in a time when the televised version of the Civil Rights movement was still running hot, keeping fire to the notion that blacks from the South were all to be pitied, tolerated, and taught how to be full humans. It was also before presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton had shown Americans outside the South that not everyone from the South was a low-IQ country bumpkin.

When I arrived in San Francisco, it felt as though I were no longer in the same country, so vast were the differences between the deep South of the Mississippi I had left and the far West of the California where I now found myself.

The language was the same, sort of. I understood the people around me. They spoke the kind of English I was used to hearing on the television and in the movies. Their speech sounded like the English I read in books. But many claimed not to understand my southern English or my idioms. And when they did understand me, they dismissed my southern speech as quaintly funny and focused on the humor instead of what I was saying. The slow musical rhythm of my speech was taken not as cultural norm, but as a sign of a slow intellect. In either case, I was not to be taken seriously. Though I was aware that I was neither quaint nor dull-witted, I was working against others’ perceptions. I decided that I would have to learn a whole new English and new ways to use the English I had.

Through careful listening and imitation, I learned to change the pronunciation of most of my vowels and to put accents on different syllables than the ones I had learned in grade school. And I learned to hurry over some words, not even pronouncing all their syllables, never giving them time to luxuriate in my mouth before rolling off my tongue and into the world. I learned to be more direct and less pictorial in my speech. I learned to say, “you guys,” instead of “y’all” even when referring to a group of girls. Speaking in these ways to avoid standing out so much from my classmates at my new high school meant suppressing my mother tongue. It sometimes meant a few seconds of lag time while I translated a thought from my Southern black English into a California regional neutral English. But with time I acquired the new English, or so I thought. I have come to realize that I am in fact a sort of bilingual with an internal monologue that has the cadence and idiomatic nature of southern speech. This inside language sometimes finds its way into the outside world in blatantly recognizable ways, and I have been told by people who pay attention to speech patterns that I have not been entirely successful in scrubbing out the rhythm and pronunciation of my mother tongue, that it is there undergirding my speech, and more apparent when I am in certain moods, or tired, or stressed.

This possibility of letting southern-sounding words or idiomatic expression slip out and betray my Mississippi background was a source of high anxiety when I was first acclimating to my new world.

Language was but one of the pieces of my life that I needed to become conscious of and to modify if I wanted to survive comfortably in this new land where I had no roots, no specific community, no history of any kind to fall back on. There were customs and mores in this big western city that differed significantly from those of small town Mississippi. From the simple courtesies of saying “Yes, ma’am” and “no ma’am” to elders and greeting each person I encountered, especially other black people, with “Good morning” or “Good evening,” to the more complex questions of how, as a young black female, to interact with the solicitous white sales clerks in the major department stores downtown, or the Chinese family that ran the corner store and laundry service at the end of our block, or the white boy in my American history class who asked me out on a date.

Food and the culture around preparing and consuming it was a whole other area of life that was different from Mississippi to California. A lot of the foods we were accustomed to in the South simply were not available. And then there was a whole world of foods that we had to acquire a palate for—foods like avocados, broccoli, and tacos. In the first few years we were in California my mother had the hardest time searching grocery stores all around the city trying to find the ingredients for traditional holiday meals such as hog-jowls, hamhocks, black-eyed peas, and collard greens for the New Year’s feast.

Clothing and the appropriateness of certain items of clothing for specific occasions was another issue. We would show up to events dressed in what would have been the right attire back home, only to be laughed at, teased, or ignored because our “country hick” was showing. My mother, a regular Baptist church-goer before we left the South stopped going to church after a few tries and getting the sense from various encounters that she was being judged harshly because her Sunday best was out of place. Eventually she found a denomination that was accepting of her, but it took years.

The fast pace of life also took some adjustment. Coming from a cultural reality where life moved at an easy pace, where the journey often seemed more important than the destination, it was hard to appreciate the fact that everyone was so often in a hurry and stressed by the fact of time. In this new land one was penalized and judged harshly for not living life like it was a fifty-yard dash, and some people took my easygoing attitude toward time as a personal affront.

But in some ways, what took the most adjustment was the way in which coming from a small Mississippi background of deprivation where so much was denied to me made me hungry for every bit of everything that was now opened and laid out before me like a smorgasbord. I took nothing for granted—from the material to ethereal—nothing. I was open to all sorts of experience, including uprooting myself again and stepping once more into a migrant stream when my high school counselor encouraged me to apply to and attend an East Coast university.

What came much later for me was an understanding that by working so hard to fit, to belong in the new place, I was erasing important parts of my identity. The problem with that kind of erasure is that there are so many different ways that a migrant, just like an immigrant from another country who arrives beyond a certain age, is never fully at home in the new land. (Some psychologists will tell you that the certain age is around six or seven. Some psychologists and social scientists will tell you that if you are raised by people who migrated or immigrated when you were just a gleam in your parents’ eyes when they arrived at the new place, your interior self will still be constructed on the foundation of that native place, which dictates the inflections in your parents’ words and the unguarded manners and behaviors in the home and the parents’ philosophical orientation to the world.) This never feeling completely at home inevitably causes one to bump up against the question of identity—the question of “who am I really?” If one has done too good a job of erasing, the answers are difficult to excavate. Thus the migrant is often left with the sense of being permanently displaced, always a little bit on the outside, even when one has learned the customs and the language of the new land and it no longer feels foreign.

Perhaps I am assigning too much to all migrants from my own migrant experience. But what I know is that migrants tend to gravitate toward people with similar roots who offer even a whiff of the homeland. For example, my cousin and I survived our first year of high school life in California by forming our own little clique of girls who were as fresh off the boat as we were—two sisters also from Mississippi and one girl from Arkansas. My uncles all married women who were also migrants from the South. And through my times of zigzagging across the county, calling different places home, I have often encountered other displaced Southerners who, regardless of race, class, and gender identification have sought to connect on the basis of our shared childhood culture, for the South is like no place else.

But the shared migrant experience also crosses regional lines. At times I have connected with people who moved from other parts of the country besides the South. Sometimes what was shared was simply the fact of not “being from here” wherever “here” happened to be. The connection was around knowing the experience of moving from one part of America to another, suddenly feeling like a stranger in a strange land and needing to reinvent and design a new self for the new location. Even when the migration is voluntary and desired, there is still a complicated reckoning that must happen.

***

My family did get a nicer slice of the American Dream Pie once we left the South—a few college degrees among us, home ownership, better jobs and good careers, more freedom to set our own paths through life, and in general more options and optimism for future generations. But we all still behave like displaced persons in one way or another, still relating to that mythic home, whether running away from it and its memory, or running toward it as two of my siblings have done by moving back to Mississippi.

When I visit the South and I find comfort in the rhythm of the language and the pace of life, I feel my roots relaxing and pushing in to familiar soil. But I am also aware that my experiences as a migrant adapting to different lands have made me into a hybrid of sorts—an American with branches from different parts of the country grafted on to the original plant, belonging at once to Mississippi and California—and belonging at once to neither.

A wonderful picture of Paulette’s journey, beautifully written as is her norm. “different parts grafted on to the original plant” is a phrase I will never forget and truly wish I could steal 🙂 Well done.

Thanks, Danny! You have my permission to “borrow” the phrase any time it suits you. I take your wish to use it as a great compliment.

Beautifully written .l was so please with the telling of this story.keep up the good work.

..

Beautiful, articulate, and intimate. Helen Vendler once told me that every poet who writes from their own personal experience lights up part of the map. Thanks to Paulette for the torch you’ve raised.

Nancy, how nice to be thought of as offering more light into the world. I always hope that my written words bring light to others. Thank you for saying that is so!