Celebrating Spring in Egypt

Since the beginning of recorded time, the land of Egypt has been intimately connected to agriculture, nature, and a spirituality that formed the basis of the values and way of life inherent in that culture. Egyptians believed that death was but a continuation of this wondrous life and that the dead were to be resurrected, provided the soul was not burdened by evil doings.

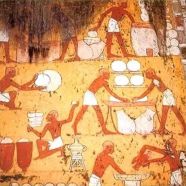

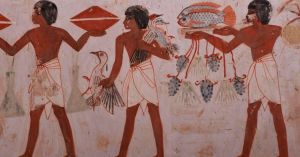

For millennia, this ancient civilization was represented in a wealth of engravings and scripts that enliven the walls of magnificent temples and awe-inspiring, colorful tombs, which remain intact due to the country’s special dry, temperate climate. Aspects of everyday life in ancient Egypt were documented in great detail giving evidence of a people with an amazing zest for life. Scenes of planting, harvesting, fishing, playing musical instruments, dancing, performing acrobatics, and more depict a hard-working, lively society living in harmony with their land.

Their keen observation of nature and its changing phases assured them that physical life went through cycles of birth, death, and renewal. The land itself testified to this belief as it was submerged by heavy floods, then lay barren until seeding time, only to burst into vegetation four months later.

The Pharonic year was divided into three seasons. Flooding, called Akhet, from July to October; planting, or Perez, November to March; and harvesting, Shmu, April to June.

The harvesting season was dedicated in honor of the fertility god Min and many celebrations were held during this season of Shmu to give thanks to the gods and welcome spring with its multitude of vegetation. Egyptians flocked to the outdoors and feasted on special foods, which were symbols of spring. Green onions, cos lettuce, chickpeas, salted fish from the sacred Nile, and of course boiled eggs. At that time children would paint ostrich eggs and write their wishes on them. It is believed that the origin of Easter eggs comes from that ancient tradition.

This festival, unlike many other religious, political, or civic festivals, has endured for over 5000 years, whereas others have lapsed due to popular disinterest. The secular, nature-based celebration of Shmu stayed close to people’s hearts through the millennia. Ancient literature contains many hymns and prayers composed at that time of year lauding the beauty of new blossoms, the notable blue lotus flower floating on the surface of the sacred lakes, and the multitude of birds hovering around and nesting in trees.

With the advent of Christianity to Egypt around the secondary century CE, the Coptic Orthodox Church celebrated Christian Easter on the first Sunday after the first full moon that follows the vernal or spring equinox—around March 21. This date is based on the Julian calendar and differs from the Gregorian solar calendar followed by Western Christianity.

Coptic Christians broke their month-long Lenten fast by celebrating on the Monday after Easter Sunday with the popular feast of Sham El Nesseem, an Arabic name meaning “Sniffing the Breeze,” as a remembrance and continuation of the ancient Shmu spring festival. Egyptians remained loyal to the ancient traditions steeped in a veneration of nature and its blessings.

Modern-day Egyptians of all religions and classes cherish and relive this joyful spring feast of Sham El Nesseem. Moslems and Christians alike celebrate together by gathering in green spaces and gardens or boarding Fellucas to glide peacefully on the majestic Nile, or Habu, as the ancients called it. Lively songs and music express the joy of spring and the traditional foods are enjoyed. Carts hawking fresh chick peas rumble down the streets in some popular neighborhoods; shops offer the famed salted mullet (fesikh), which is eaten with green spring onions and scooped up with loaves of whole wheat pita bread. Colored boiled eggs are served to the excitement and joy of the children. Families and friends enjoy the outdoors until sunset, reenergized by the sounds and sights of nature.

The date for Sham El Nesseem changes each year along with Orthodox Easter, which fell this year on May 2, which meant the spring feast was celebrated on May 3. It so happens that this year it coincided with the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, which follows the lunar calendar, a month during which the majority of Egyptians fast. Because of this festivities may be modified or postponed.

To Egyptians, this ancient feast of Sham El Nesseem embodies the belief in the power of nature to bring communities together to honor the life forces of the land and its legendary river Nile. It is a festival that will endure as long as Egypt itself. So, as is inscribed on the tomb of Inherkhawy:

“So seize the day! Hold Holiday!

Be unwearied, unceasing, alive you and your own true love

Let not the heart be troubled during your sojourn on Earth

But seize the day as it passes”—Translated by J. L. Foster, dated 1160

What a beautiful piece, expressing so well the Egyptians’ enduring appreciation of the cycle of life and their celebration of nature and its yearly renewal. The author shows a wonderful sensitivity towards, and a deep understanding of, Egyptian civilisation that lives on from ancient times till the present.

What a wonderful story of Spring in Egypt. It was so well researched yet had the feel of a tale relayed by a folk tale,Thank you for sharing this piece.

Thank you, Samia, for this lovely piece. I was especially moved by your telling of Christians, Muslims and all religions and classes celebrating Sham El Nesseem together. A perfect way for humankind to affirm, as you said, “the power of nature to bring communities together.” Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the whole world would join together in this celebration of the land from which we spring.

A beautifully written and informative account of the history of the festive feast of Sham El Nesseem that unites every Egyptian regardless of their religion and social class. What is especially poignant is it clearly reflects Samia’s awe of ‘our’ ancient heritage, and her deep respect and appreciation of nature.

Well done, Samia.

What a lovely tale of a reality that has survived so many eras and so many changes in the culture of Egypt and yet remains a vital part of Egypt s heritage and present. Very enjoyable reading. Congratulations to the two Samias

Thank you Mom for sharing an informative and highly delightful narrative on one of Egypt’s most popular cultural celebrations that is so close to our heart.

I believe its so important to have a space where fresh and new content can be shared to shed light on the richness and magic of different cultures. With time it can hopefully shift so many singular perceptions towards our region.

Proud Daughter

Such an interesting , well researched article. With wonderful flow it takes us from past to present bringing out the spirit of joy and festivity associated with Sham el Nessim. celebrated by all Egyptians throughout the ages.

It is so wonderful to read about how “we” basically started it all!

Agriculture, calendars, gender equality, you name it, and of course celebrations.

My only wish is that more Egyptians recognize the uniqueness of our history and culture, and how much humankind owes us.

You are one of those my dearest cousin Samia, who reminds us of our amazing heritage.