Coping with Covid-19 in the Cold: A Wintery and Wooly Wonderland

Norway, a sparsely populated country close to the North Pole, has seemingly tackled the Covid-19 pandemic better than many others. Not just in keeping the number of cases low; but also, mentally, during intermittent lock-downs. How? By embracing the big outdoors, even when it’s freezing out there.

Some would claim it’s in our DNA; we even have a word for it: “Friluftsliv”—which literally means “free air life” but actually means any outdoor activities at all, from those involving physical exertion to just lounging around in a hammock in the forest. Friluftsliv is done all year around, and during winter these activities are closely tied to snow. It could be skiing (mainly cross country, as trails are “paved” in the form of double tracks found everywhere and accessed by everyone free of charge), ice-skating, tobogganing, kick-sledding (look up “kicksled” on Wikipedia!), or just making snow angels and goofing off. It most certainly involves a thermos with hot cocoa or coffee and waffles with jam, or barbecuing some hotdogs—preferably in the middle of nowhere. But, most importantly, it involves wool.

When I wrote the book Ren ull (Pure wool) with coauthor Ingun Grimstad Klepp, a research professor at Consumption Institute Norway at Oslo Metropolitan University, we asked HRH the Prince of Wales to write the foreword. He said “yes,” as he is the patron of the Campaign for Wool, but asked us what he should write. We (jokingly) suggested that he could offer that the explanation for Roald Amundsen beating Robert Scott to the South Pole was due to wool. He actually wrote the following: “Your Norwegian knitted sweaters are famous throughout the world, and we are happy to concede that Norway won the race to the South Pole at least in part because of the excellence of your woolen products!” Luckily for Prince Charles, the book was never published in English.

In our later books we expounded on this, specifically in our Norsk strikkehistorie (History of Norwegian knitting) and Lettkledd (Easy wear—well-dressed with little environmental impact) (both also only available in Norwegian). It is clear that Norwegians’ rather extreme ties to nature and being outdoors in all types of weather did spring from our explorer heroes conquering the most inhospitable outposts of the globe at a time when our country became independent from Sweden, and before that Denmark, and when we needed to build our national story. In order to tackle the cold, however, knowledge of how to dress for cold weather activities was crucial. Activity generates sweat and moisture and, with the wrong clothes, this can be fatal. Dressing for comfort means understanding the intrinsic properties of fibers. Wool has one unique property: the fibers do not collapse when wet and can absorb up to more than 30 percent of its own weight in moisture without feeling wet. Also, when wet, the temperature in the wool actually rises.

One could actually claim that wool is also part of our DNA, as our survival this far north depended on the fiber, either as pelts or spun into yarns.

We find wool in the “sea mitten” story and in the “varafell” or “boat throw” story as well. Both stories go back to prehistoric times and tell of how wool enabled the Vikings to travel as far as Constantinople and America in open boats in freezing cold water and in all kinds of weather. Sea mittens (which may have looked a lot like Bernie Sanders’s iconic mittens) were knitted or, originally, “needle-bound,” which predates knitting (look up “nålebinding” on Wikipedia, where the technique is explained using the Old Norse word). The wool, taken from the Old Norse sheep breed, is dual-coated with coarse guard-hairs and has a soft, downy underwool. These mittens would quickly become wet when rowing, which would felt the wool; once felted they could be dipped into the ice-cold seawater to offer warmth while fishing. (Yes, I know this sounds like magic, but just do it: Dip wool into cold water and insert a thermometer and watch as the temperature actually rises.)

The “varafell” is a woven cover that emulates fleece or a fur rug through a special weaving technique on a warp-weighted loom, where loose wool is woven into the weave itself. Voilà: Cover in open boats without the danger of rotting, which would happen to fur skins when exposed to salt-water. This cover could be used both as a blanket and as a raincoat (or maybe a rain poncho), as the coarse guard-hairs of the Old Norse sheep function as nature’s own Durable Water Resistance technology—without the toxic chemicals.

As you may have noticed, Prince Charles mentioned the world-famous Norwegian knit sweaters. When Arnold Schwarzenegger visited Norway in 2010 to talk about the environmental and climate challenges we face, he took time out to visit Dale of Norway’s flagship store in Oslo. For him, Dale of Norway was an iconic brand that he knew from the Alp ski resorts he grew up near and certainly from Vail and Aspen, where their luxury sports stores have been selling Norwegian knitted sweaters and cardigans since the 1950s. In fact, the history of how ski resorts in the US are tied to Norwegian knitted sweaters and mittens has been studied by Susan Strawn. However, these bulky sweaters are not the only way to embrace the outdoors. The more streamlined alternative is the next-to-skin merino wool revolution. And here we need to engage with the ski hero Vegard Ulvang. He was a heartthrob in the 1980s, winning medal upon medal in international cross-country skiing competitions. As a journalist for a popular youth-oriented magazine back then, I may have contributed to this sensation. What he achieved in the 1990s was a revolution, or rather a rewoolution.

Ulvang (notice the name and how close it is to the Norwegian word for wool—ull) was a hero at a time in history when celebrities were “on call” when media demanded you to be on call. That meant as soon as you crossed the finish line, media wanted access. If you’ve just sweated for miles on end, and then suddenly need to stand still to be interviewed by journalists, you will—if you are wearing anything but wool—become cold and possibly sick. Most skiers were wearing synthetics and, as Ulvang told us, “We were wearing what is in essence fishnet. It is ice-cold the minute you stop in your tracks. There is absolutely no warmth.”

After he launched the next-to-skin Merino-wool-based underwear in the late 1990s, he was instrumental in a very important change. It started with children in kindergartens. During the first decade in the new millennium, Norwegian kindergartens started to demand that the kids dress with wool “innermost” as soon as the temperatures plummet toward zero. More companies copied Ulvang’s idea and the array of functional wool long-johns, undershirts, tights, bras, boxers, and panties hit the stores, even the supermarkets. These items were colorful and fun and had the added benefit of needing less laundering, as Norwegians learned that wool can be aired rather than laundered after use. A true change in clothing took place.

So, what does all this have to do with Covid-19 and coping? Let’s add to the mix a Northern European concept of “freedom to roam,” or “everyman’s right” as it’s called. You find this notion of the right of public access to the wilderness in Scotland, Finland, Iceland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Austria, Switzerland, the Czech Republic—and Norway. Oslo is one of the largest cities in Europe area wise, and the physical center of the city is actually in the middle of the forest that surrounds us. In addition to this, many families own at least one cabin, which gives them access to the great outdoors more or less on their doorstep.

And here is where the last coping clue comes in. Cozying, or “kos” as we call it, is the reward after a long cross-country ski trip or ice skating on a frozen fjord or lake: Sitting in front of a toasty fireplace with a blazing fire with a knitting project, a Nordic noir crime novel, or just a glass of red wine. You may recognize the image from the Danish “hygge” craze—however, I would claim the Danes stole the idea from us and as usual were the ones to capitalize on it. We just took it for granted—the Danes aren’t even that good at knitting (though they are the masters of Nordic noir). We don’t have good numbers, but from what we’ve been able to surmise, Norwegians have twice as many active knitters as our neighbor countries. The pandemic has even increased this, or at least the activity, as the largest spinning mill in Norway—Sandnes Garn—in 2020 increased sales close to 20 percent, with 13.7 million balls of yarn sold. Many other spinning mills in Norway report a similar upswing in business.

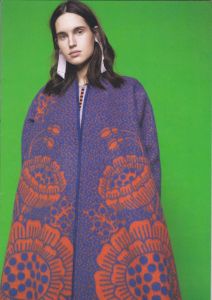

When art and fashion historian Ragnhild Brochmann recently described the interior trends for 2021, she called on coziness and the handmade and artisanal as the core of what the pandemic has brought into play. “We want to see traces of the hand in what we surround ourselves with,” she told the reporter in TV2’s Morning show and went on to describe something very akin to cocooning. You may remember the onesie—a Norwegian invention—may very well be making a comeback. Personally, I prefer my throw-coat, which offers the same effect whenever I walk out the door with my wool underwear, my wool joggers, and my wool face mask. The Norwegian designers E S P, Oleana, and Tom Wood have all developed oversized coats based on woven throws, which have found their way to an international market. That said, actress Bo Derek was a trailblazer when she acquired one of these coats back in the 1980s. It’s like walking outdoors enveloped in a blanket, but oh so cool. The Norwegian Museum of Decorative Arts and Design even purchased one of Oleana’s throw coats for their permanent exhibit.

Communing with nature has been written up as one of the main coping mechanisms for humans, offering psychological benefits above and beyond what pills or other chemical solutions “solve” in the face of depression during lock-down. But living in a climate that is cold for more than six months a year, we need to know how to dress in order to access this resource. “There is no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing.” We like to think this is a Norwegian saying, but it surfaces in other countries as well. I would claim, though, that no other country understands as well as we do what these “good” clothes are. Our Norwegian haute couture designer, Per Spook, even brought this knowledge to the Parisian catwalks and shocked the fashion world by offering women warm and practical clothing “so they can run after the tram without tripping in their high heels and too narrow skirts.”

Perhaps I can offer one last explanation as to why Norwegians seem to tackle this tragedy better: We never completely embraced the high-speed pace of current society. Fast fashion irked us. Working long hours was not in our DNA. We would rather spend quality time with friends and family, escape to the cabin, head out into nature—than jet to London or New York. We tried (hard) to become those sophisticated, urban, Bizz Wizz, savvy, and cool cucumbers. But once the pandemic hit, we let out a collective breath. Who are we fooling? We’re one short generation from the farm, the woods, the sea. Nature was still calling us.

The pandemic gave us the time and the space to hear her call. And that is what will ground us when we need to build back better. We embrace the darkness, as it is the place where we can see all the stars in the universe. And thus, see how we are not actually the center of this universe. Thinking we are, was probably what brought us here.