Sarah Greene tumbling in the snow with her first paycheck. Photo credit: Dallas Morning News, early 1950s.

Share This

Print This

Email This

First Flight

My mother wanted to be the first journalist in space. I read this news, as if for the first time, while going through a shoebox full of old letters. What a shame, she wrote, that she had missed the deadline for NASA’s search to find a journalist to send on one of the space shuttle missions. The letter was postmarked January 22, 1986—six days before the explosion of the Challenger.

A Smithsonian Magazine article published earlier this year reveals the details of a story that anyone could have guessed. After the tragic loss of the first schoolteacher in space, Christa McAuliffe, it was time to reconsider any thought of placing more civilians at such risk.

The laudable if unrealistic aim of the program to put civilians aboard the shuttle had been to broaden our understanding of space travel by having it described by ordinary Americans. James Michener served on the task force that recommended its creation. As he said at the time, “We need people other than MIT physicists to tell us what it’s like up there.” The second civilian astronaut, had the program continued, would have been a journalist.

With the application deadline having arisen before the Challenger launch date, the competition had attracted some 1,700 applicants, including such luminaries as Walter Cronkite, Tom Wolfe, and William F. Buckley Jr. If the program’s administrators had wanted to assure themselves of “an eloquent contribution to the literature,” as a spokesperson put it, they could have taken their pick of nationally acclaimed writers. Who’s to say, though, that they might not have gone a more populist route and favored Sarah Greene, the fifty-seven-year-old editor and publisher of the Gilmer Mirror, a thriving small-town Texas newspaper? (That is, had she turned in a timely application.)

My mother died three months ago. She had been dying for a long time—long enough to have to make the heart-rending decision to put her house, unoccupied for years, up for sale while she lived. Selling the house meant emptying the house of its contents, a daunting proposition. The very prospect had stopped every conversation I’d tried to have with her about moving to a place more suitable for aging. How would that work? she would ask. Every wall, every corner of her light-filled, split-level house held treasures accumulated over more than eighty years of living, sixty of them spent as a journalist with a yen to travel. An archivist by instinct, she saved everything. An inveterate reader and a collector of Texana, she owned a collection that could have stocked a small rare book store. She couldn’t imagine uprooting herself from all of that. As her health failed she moved out by degrees, and not by choice. Dealing with the consequences fell to me.

It was Chapel Hill’s own Bill Ferris (speaking of archivists by instinct) who suggested that the papers of Sarah Laschinger Greene deserved a home in the University of North Carolina’s Southern Historical Collection. She was, after all, the third-generation owner of a newspaper in East Texas, which, no matter what anyone tries to tell you, is part of the South. Luckily, the Southern Historical Collection’s director, Bryan Giemza, agreed. With this destination in mind (I had already found a ready buyer for her collectible books), I began the slow process of sorting and boxing.

And that marked the beginning of the process of understanding who my mother was, as if for the first time.

I found the blank NASA application. I even found evidence of her very first airplane flight. She was still a schoolgirl. World War II was on. While she was visiting a cousin in Waco, the two of them had gone to check out the Army Air Field (headquarters of the Army Air Force Central Instructors’ School). Pilots were offering rides, for a price. Her cousin parted with a $50 war bond, and up they went.

Her parents learned of this adventure by mail. Perhaps there was no time to ask their permission, or possibly it was the trick of asking forgiveness. That might have been smart. A couple of years later, in 1945, she enrolled in Stephens College, the women’s college in Missouri. Stephens offered an aviation program, a serious curriculum, the first such program for women in the country. She was going to learn to fly! But since she was only sixteen, she couldn’t enter the program without her parents’ consent, which they refused to give.

This sad story was a familiar one, retold many times; indeed, she never got over it. What I was astonished to learn is that, before their change of heart, her parents did consent, and for about twenty minutes she lived the dream: she got to take a flying lesson. “There really wasn’t anything to it,” she reported in a letter home. At a maximum speed of 80 miles an hour, the flight would have taken her several hundred feet above the ground, just enough to taste the possibilities. “The instructor let me fly it alone a lot and I learned how to turn and go up and down and even how to land,” she wrote. “It was really a lot of fun.”

Forty years later, the Challenger must have looked like another grand chance.

* * *

The traces my mother left behind fill in many particulars of how she lived. More than that, I’ve come to realize, they offer a blueprint of how to live.

Judging by how well I remembered the startling revelation of her interest in space travel, I must have skipped a few lessons. By 1986 I was finding my way as a Washington lawyer, always working too hard, self-absorbed in my Beltway world. We wrote often during those Reagan years, madly exchanging newspaper clippings that exposed the latest outrage against women or common sense. We were each other’s best friend. But, in retrospect, I wonder if we didn’t sometimes talk past each other.

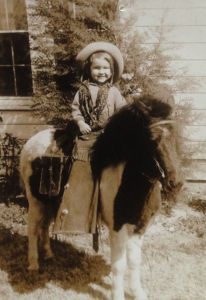

We knew we differed on one crucial topic. Proud as she was of my achievements, she longed for me to return to Texas. She was a fanatical Texan, a “professional Texan” as my husband would say, which she suspected was an insult (it was not). Her heart belonged to East Texas, with its piney woods and distinctly Southern traditions. But she fell for the whole enchilada, the Texas that the rest of the country recognizes. This is the land of “cowboys, Indians, Texas Rangers, mustangs, humble Mexicans, ranch life, and buried treasure”—a world largely invented by J. Frank Dobie, as writer and critic James Ward Lee wryly notes. But no matter. She had her own horse by the time she was eleven.

My feelings were more complicated. Texas was my home, but I’d never bought the mythology, and by the time I’d finished law school I’d become pretty discouraged about the career prospects. During my summer as a law clerk in Dallas, one lawyer helpfully offered this tip: “Women don’t do well in the courtroom here—except in domestic relations cases.” No workplace was free of sexism, I knew, but I’d encountered nothing as bald as that in Washington.

As my mother became more interested in the Texas literary scene, her letters shared news of emerging critical conversations. She sent me a talk by Celia Morris, a keynote address given at the Texas Women Scholars conference held in Austin in 1986. Ironically, what I found in those pages managed to seal the case against ever returning to Texas. Though that photocopy is long lost, what it said to me has been etched in my memory for thirty years. Now that I’ve tracked it down again, my eyes go straight to this passage, and the same sinking feeling returns:

Our state is known to the world, and, I fancy, often to itself, primarily by the things men do outdoors—by wars in its early days, gradually by cattle, subsequently by oil, and now by football. Its mythos is overwhelmingly masculine. Although one of my contemporaries wrote of herself as profoundly shaped by the strong women stretching back in her family, she, her sister, and daughter agreed that they had always felt somewhat cheated, or at least left out, “because we had no real feel for the Texas that everyone else seems to have: the land, cowboys, oil wells, cattle, Indians. . . . None of us feels at all affected by having lived among these legends, neither infused with them nor sentimental about them. Not much interested and not affected.”

If that’s how it is, I remember thinking, I’m not much interested. No real feel for it. I’m sorry.

But I didn’t entirely grasp Morris’s point. I don’t think I ever got past that stinging indictment. Had I followed her argument through, I would have found that she had some advice for Texas women. Read widely in the works of other women, she suggests. Read the novels of Shelby Hearon and Beverly Lowry. Read Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s important study Revolt Against Chivalry, the story of Texas suffragist and anti-lynching advocate Jessie Daniel Ames. Read beyond Texas, for “women writers outside our tradition can also help us feel what life inside may have been.” Her reading list includes Rosellen Brown, Alice Walker, and Lee Smith.

In time I would find my way to Chapel Hill, where I would come to appreciate Jacquelyn Hall and Lee Smith as writers and as friends. I didn’t enter graduate school to study the literature of Southern women, though. Rather, I trained my sights on British literature. A dissertation on Virginia Woolf and the Renaissance fed my yearning for Big Ideas. But that wasn’t all I got out of the bargain, for to study Woolf in the 1990s was, of course, to become immersed in the new feminist discourse on the lives of women, including those women writing their own lives everywhere from North Carolina to Texas.

My mother, unsurprisingly, stayed a couple of steps ahead of me. The 1992 paperback edition of Shelby Hearon’s 1978 novel A Prince of a Fellow contains an afterword by Sarah Greene.

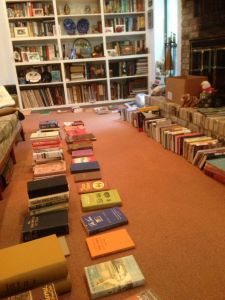

I came across her copy of that book (I had forgotten about it) about a year before her death, while organizing her cherished Texas book collection for sale. In 2007 she had compiled a thirty-seven-page inventory, noting each book’s edition and condition, whether it was signed and to whom. Only after I had shopped the list out to the few possible buyers I could identify—the universe of rare book dealers is not what it once was—did I realize what a task I had set for myself. I had a list, but it wasn’t current. What would be missing, what recent acquisitions would need to be added? Books were everywhere: in the laundry room, in the linen cabinet, in the bottoms and tops of closets, in crates, behind hidden doors. In a whirlwind few days that bled into long nights, I sorted and stacked hundreds of books.

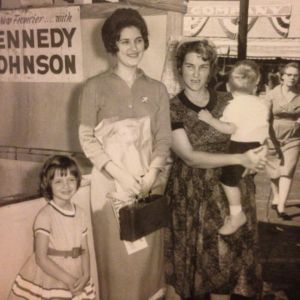

Sally Greene, Lynda Bird Johnson, Sarah Greene carrying Russ Greene, taken in October 1960, in Gilmer, Texas, by Ray Greene

In the midst of the frenzy I took a moment to sit still. For the first time, I began to think about the collection as a whole. At the heart of it was folklore, reflecting a long love affair with the Texas Folklore Society. There were also books by and about journalists, famous and infamous, books about politics (every one ever published about LBJ or Lady Bird). Art books. Photography books. Limited editions exquisitely produced by a master printer, and vanity-press paperbacks personally inscribed by the author. What struck me was that so many of the books were personal narratives or biographies; or that they reflected a singular obsession. Here were Virginia Woolf’s “lives of the obscure,” each one crying out, Here I am! Read me! I wanted to read them all. How could anyone read them all?

Beyond the Texas books, I found books by Lee Smith, Hal Crowther, and Elizabeth Spencer, with all of whom she enjoyed enduring friendships. When she talked about Smith’s novels I sometimes felt that her interpretations were naive: she wanted to know how much of the real Lee was on display. The biographical fallacy! protested my inner New Critic. What about the novel’s form, or its feminist argument? But she was not wrong to seek the essence of a real woman’s experiences. The connection to the mind that could imagine an Ivy Rowe or a Molly Petree was, indeed, what she read for.

As the sorting and sifting continued (four hundred books dispatched to the public library), I kept coming back to the wall of books remaining in the living room. The books my mother kept there were not particularly valuable, but they were deeply valued; quite a few dated from before I was born. Among them was a modest representation of existentialist thought. I knew that her core beliefs reflected the existentialist idea of radical freedom and its corresponding responsibility. In a particularly dark period, she clung to Camus’s assertion that the “one truly serious philosophical problem” is whether to go on living each day. These ideas sustained her for a lifetime, through grief and depression, divorce, and the seemingly endless suffering that defined her final years. What I had never realized is how existentialism must have shaped her passion for all those stories.

A wise, witty, and perfectly timed new book, Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Cafe, locked these pieces into place for me. Transporting us to 1930s Paris, seating us at the table with Sartre and de Beauvoir, she invites us to share their excitement in discovering Husserl’s theory of phenomenology. The phenomenologists broke from traditional Cartesian philosophy, with its lofty abstract theories of knowledge, and “went straight for life as they experienced it moment to moment,” writes Bakewell. There is no detached perspective from which to view the world. All the existentialists agreed on this much, however else their views differed. Although one aspect of the focus on being is the solemn concept of absolute freedom, existentialist philosophy contains ample room for delight in the sheer multiplicity and variety of life. It would have been a congenial habit of mind for a woman with boundless curiosity and a reporter’s keen skills of observation.

By the time I might have wanted to talk with my mother about these ideas, I wasn’t much interested. Existentialism had gone out of fashion. My graduate school years were spent in the airy realms of structuralism, poststructuralism, and assorted other -isms, all of which skittered right away from the solid grounding of lived experience and back toward those numbing abstractions that the existentialists so resisted. But I’m coming around.

The principles of phenomenology begin in observing the world, but they don’t end there. They include the lovely concept of “being-in-the-world.” This is the idea that we come to consciousness already woven into the fabric of the world around us, that self and world are interdependent. I see my mother enacting this principle as well. Thoroughly involved in her community, she was quite happily shaped by it. She reflected it back to itself in each issue of the Mirror. The newspaper, the legacy gift of her parents, anchored her in history, and her work enriched its value and expanded its reach.

To speak of being-in-the-world is a way to speak about place. Merleau-Ponty puts it like this:

I am a psychological and historical structure. Along with existence, I received a way of existing, or a style. All of my actions and thoughts are related to this structure, and even a philosopher’s thought is merely a way of making explicit his hold upon the world, which is all he is. And yet, I am free, not in spite of or beneath these motivations, but rather by their means. For the meaningful life, that particular signification of nature and history that I am, does not restrict my access to the world; it is rather my means of communication with it.

Writers know this. When poet Jeffrey Thomson, for example, speaks of place not as a particular place but as “a concept that creates and defines how we as human see and experience the world,” he echoes Merleau-Ponty.

And my mother knew this. Two things you “ignore at your peril,” I find her writing to me more than thirty years ago: “the dailiness of life and the significance of place.” Texas happened to be her place. But I don’t think she ultimately meant that Texas had to be my place. Enfold yourself in the world around you, she was saying. Imperfect as it is, it is filled with beauty and surprise, and it’s all that you know. Hold it close. Hold on to it as long as you can.

* * *

At a concert in Saxapahaw, NC, last spring, the talented Greensboro, NC, singer-songwriter Laurelyn Dossett performed a song that spoke directly to my experience, to this sense that in her dying, my mother was leaving me untold gifts that I was simply unable, or unready, to acknowledge while she lived. I couldn’t quite remember the line that moved me so: was it “Dying is the best act of love”? “Dying is the last act of love”? So I asked her. She thought it must have been from “Leaving Eden,” a beautiful ballad in the voice of a wife and mother forced to call upon her own strength as a mill closing uproots her family, though she pointed out that she didn’t think the song said exactly that. (“But things have different meanings to different people,” she gently added.) She was right: the lyrics say nothing of the sort. I heard what I needed to hear.

“Then you should write that song,” I suggested to her. I hope she will. For we must be legion, all of us for whom the loss of a parent sparks an unexpected journey into a deeper understanding of ourselves, and of what we need to do to live into the wisdom that comes as a consolation: the last, best act of love.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time. (―T.S. Eliot)

Beautiful. Touched by the beauty of these words and your mom’s wise message, “.Two things you “ignore at your peril,” I find her writing to me more than thirty years ago: “the dailiness of life and the significance of place.” Texas happened to be her place. But I don’t think she ultimately meant that Texas had to be my place.”

I understand this more each day.

When I quote my mother, as I have several times in this past year, I appreciate her much more now and the gifts she gave me.

Sally, your comments are so on target! I’ve known Sarah since we were in the sixth grade. Although our paths took separate ways, we were always together whenever the opportunity arose. I’ve missed her so very much. thanks for sharing your thoughts.

So glad this maddest to you, Jane. You were indeed one of her oldest and best friends. I know she treasured you. Thank you.

Posted before coffee. So glad this made it to you!

Thank you – a beautiful piece I’ve shared with my mother and sister.

I worked for Sarah Greene on and off from the time I was a sophomore in Gilmer High School until her death when I was sixty-two years old. I thought I knew her very well, for I worked in the office with her full-time for eight years of that period. I never imagined she had wanted to be an astronaut! That was fascinating. One lesson I learned from her, as a journalist myself, was not to do something that served no “useful purpose.” I think she’d be proud that Sally wrote this. I still write weekly for the Gilmer Mirror today as a free-lancer, three years after Sarah Greene’s death, and am grateful that she gave me my start in the profession I have long loved.

Thanks very much, Phillip.

Lovely- isn’t it interesting that I would read this the day before the 5th anniversary of my mother’s death 😉 so much connection.

Thank you, dear Michael.