It Was Always the River: Natchez on the Mississippi

Sometime in 2015, as I was sitting in the visitors’ center in Natchez, Mississippi, watching one of those introductory films developed for tourists, I first heard the words: “It was always the river.” They were spoken softly by a woman as the sun’s rays reflected hues of yellow and orange on the Mississippi River. Whether it was her intention, the woman whose voice accompanied that image had made a telling statement about the river’s place in the lives of Natchezeans, past and present, and it has echoed in my mind ever since.

My many visits to Natchez prior to that time had been for a book I was writing. I had been traveling there since 2012 to get to know the town and its environs and to conduct research about a murder that took place there in 1932. The crime, which made headlines nationwide and was known locally as the “Goat Castle murder,” nearly eclipsed the great publicity surrounding the first pilgrimage to antebellum homes earlier that spring. Researching and writing that book, which became Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South (UNC Press, Oct. 2017), repeatedly brought me back to this historic town that hugs the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River.

The river is the town’s raison d’être.

Natchez is the oldest settlement on the lower half of the Mississippi River and earned its name from the area’s original inhabitants, the Natchez Indians. Over time, Natchez became home to the French (who established Fort Rosalie in 1716), the English (following the Seven Years’ War with England, the fort was ceded to the British in 1763), the Spanish (from 1779 to 1798, during which time Natchez began to take shape as a city laid out in the common grid pattern under territorial governor Manuel Gayoso de Lemos), and finally the Americans in 1798, when Natchez came under the control of the U.S. government.

The town has had its fair share of famous visitors throughout its history. When it was the capital of the Mississippi Territory, former vice president Aaron Burr was arrested near Natchez for conspiring to create a separate nation, though he was released and later acquitted on charges of treason. Two decades later, the American naturalist John James Audubon spent a few months in Natchez painting birds; he also enrolled his sons at nearby Jefferson Academy, a military school for young boys. P. T. Barnum brought the Swedish singing sensation Jenny Lind to Natchez in 1851, where she performed to a sell-out crowd, as she had done in cities across the United States.

The river, and the rich lands it fed, brought northern investors from New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, who took advantage of the antebellum cotton boom, as well as the nation’s institution of slavery. Just like their Southern counterparts, these Northerners helped to create the demand for slave labor that resulted in the sale and forced relocation of between 750,000 and one million men, women, and children from states in the Upper South to the Deep South states of Mississippi and Louisiana. While a majority of those enslaved were sold in the city of New Orleans, thousands were sent upriver to Natchez, where they were sold at the slave-trading post known as the Forks of the Road.

Military control of the Mississippi River has always been strategically important, but it was particularly so during the Civil War. Once General Ulysses Grant’s troops took control of the town of Vicksburg after a weeks-long siege, Federal troops went farther south, to Natchez, where in August 1863 they occupied the town and placed black soldiers on patrol, shocking white Natchezeans. Those same soldiers, some of them former slaves, also took pleasure in destroying the slave pens at the Forks of the Road, which signaled the end of the institution of chattel slavery.

Twain, Mark. 1883. Life on the Mississippi. Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1998.

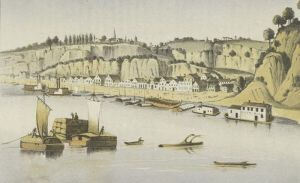

The river was, for all intents and purposes, an important highway of travel and trade in the nineteenth century. As Mark Twain, himself a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi, explained: “The river’s earliest commerce was in great barges—keelboats, broadhorns. They floated and sailed from the upper rivers to New Orleans, changed cargoes there, and were tediously warped and poled back by hand. A voyage down and back sometimes occupied nine months.”

With that commerce came some unsavory characters who helped shape the bad reputation of the land below Natchez’s bluffs. “It gave employment to hordes of rough and hardy men,” wrote Twain, “rude, uneducated, brave, suffering terrific hardships with sailor-like stoicism; heavy drinkers, coarse frolickers in moral sties like the Natchez-under-the-hill of that day, heavy fighters, reckless fellows, every one, elephantinely jolly, foul-witted, profane; prodigal of their money, bankrupt at the end of the trip, fond of barbaric finery, prodigious braggarts; yet, in the main, honest, trustworthy, faithful to promises and duty, and often picturesquely magnanimous.”

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, Natchez seemed to be bypassed by modernity. Trains replaced steamboats, and while the Illinois Central Railroad made a stop in Natchez, the river traffic nearly dried up. There was no bridge across the Mississippi until 1940, so for almost half of the twentieth century, travelers to Natchez from points west had to be ferried across from the town of Vidalia, Louisiana.

And yet in the midst of the Great Depression, travelers did venture to Natchez despite its isolation—crossing by ferry over the river to see its magnificent antebellum mansions, which made the town synonymous with Old South grandeur. This tour of antebellum homes, known as the Natchez Pilgrimage, still draws tourists to this day. And the river has once again become home to steamboat replicas that bring tourists by the thousands every year.

As someone who has made repeated treks to Natchez, I am always drawn to the river. Like Frederick Law Olmstead before me, who visited in 1852, I have sought out its bluffs to get the splendid view of this force of nature. As he noted, “the grand feature of Natchez is the bluff, terminating in an abrupt precipitous bank over the river.” And while there is now a river walk and fence to protect people from tumbling over the “precipitous bank,” it remains the place I venture to most frequently. The swift moving waters and the amazing sunsets over and beyond Louisiana continues to fascinate and thrill me. I’ve seen sunsets in blue and yellow, pink and blue, golden yellow, and one evening there was a sunset of fiery orange that nearly took my breath away. I have walked along the bluffs numerous times and have never been disappointed with what nature has produced.

Yet my fascination with the land and sky is tempered by my knowledge of America’s history of slavery, because there, under those same sunsets were thousands of acres given to planting cotton, and where the human chattel of the domestic slave trade—men, women, and children—provided the free labor that made millionaires of men in the lower Mississippi Valley, which included Natchez.

Understanding this doesn’t distract from the river’s historical significance or the place it has in the minds and memories of Natchezeans, which is why those words “it was always the river” still resonate.

I have felt the same drawing to Natchez almost as if I belong there. Visits temporarily satisfy that and reading your splendid article opened my eyes to even greater appreciation which I will take advantage of on a future visit.

Thank you for your comment, Eric. It is a fascinating place with such a rich history.

I just finished reading your book after visiting Elms Court.

I too have been fascinated by Natchez for years now and I thank you for devoting yourself to telling this story.

Natchez was considered a Union town during the Civil War. Delegates from Natchez voted against secession from the United States. Although it was a slave trade center, there were free men of color who lived in this small town until 1842 when Mississippi passed a law that prohibited the freeing of slaves.

Great article, Karen. Looking forward to another visit with you when you return to “the river”!

Your article is very enlightening .My childhood home is located between Natchez and Woodville. The history is fascinating and there is always a new thread to follow. I look forward to reading more of your work.

I rode on the Natchez boat over 30 years ago as a champeron for my son’s school field trip,we want to ride again for our birthdays in November 16th,17th.How do we nook a ride! We enjoyed it so much back then I’m sure we’ll enjoy more now.