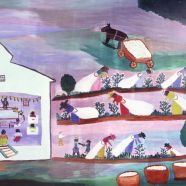

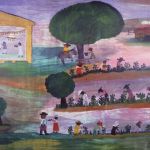

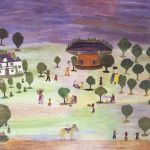

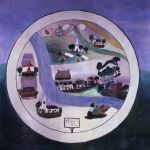

Portfolio: Clementine Hunter African House Murals

Excerpted from Clementine Hunter: Her Life and Art, by Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead by permission of LSU Press

By the summer of 1955 Clementine Hunter had been painting at least fifteen years at Melrose Plantation near Natchitoches, Louisiana. She had developed the major themes that would dominate her paintings in the years ahead. François Mignon, the writer and resident host, persuaded her to create a series of paintings that could be permanently displayed on the second floor of the plantation outbuilding known as “African House.”

Mignon had provided the name African House to the barn after his arrival from New York in 1939. Archeologists and historians have been trying ever since to provide more accurate descriptive names. But the colorful and imaginative names Mignon gave structures have survived even though in most instances they did not reflect the history or purpose. The Creole style structure, probably constructed around 1820, had been called a barn, Casa Verde and the Mushroom House. However his African House title, being more glamorous and romantic, was firmly entered into history in 1941 when the Historic American Building Survey had measured the structure, and in completing the informational sheet Mignon, when asked the name, replied “African House,” which is now recorded in the Library of Congress and subsequent history.

The murals, as he envisioned them, would provide a panorama of plantation life at Melrose and incorporate her major plantation-inspired themes in a building. Hunter had never seen a mural, but when Mignon explained to her, she accepted the assignment as “something she wouldn’t mind doing.”

When Hunter started painting the African House Murals, major changes had already begun to take place in plantation life. The labor force, so critical to a plantation’s success, had begun to erode after World War II, as workers moved north for more opportunities. Laborers came home from World War II with a realization that a chance for a better life might lay beyond the hand-to-mouth reality of sharecropping. Concurrently, the labor-intensive jobs were declining rapidly as more and more jobs traditionally done by hand were being done by machine. For the second time in a hundred years African Americans left the southern farms in search of better jobs in the auto plants, the steel mills, and the factories of the North and Midwest.

The murals hang on the four walls of the second floor of African House. Memory is a human experience that demonstrates what we believe, what we value, and how we interpret our history. Clementine Hunter’s autobiographical African House Murals provide viewers today, just as Mignon had hoped, with a detailed and inspired documentation of plantation life as it once was. While the idea to paint the murals came from Mignon, Hunter took the paints and brushes and personally defined the final product. From the point of view of a participant, she deftly told her story of Melrose and what she recalled about living and working there during the first half of the twentieth century.

*Photographs of the murals by James Rosenthal, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service

These murals are some of some of the finest I have seen anywhere. It’s surprising to find them where they are instead of a museum. The artist has really put herself into them.